Sr. Barbara Lum, SSJ, is a sister of St. Joseph of Rochester, N.Y. Originally from Rochester, she entered the community in 1953. She has served in nursing ministries at St. Joseph’s High School of Nursing in Elmira, N.Y., Good Samaritan Hospital and School of Practical Nursing in Selma Ala., and at the University of Rochester. Currently she works as a home health aide program instructor at Rochester Education Opportunity Center.

What brought you to Selma, Ala., during the Civil Rights Movement?

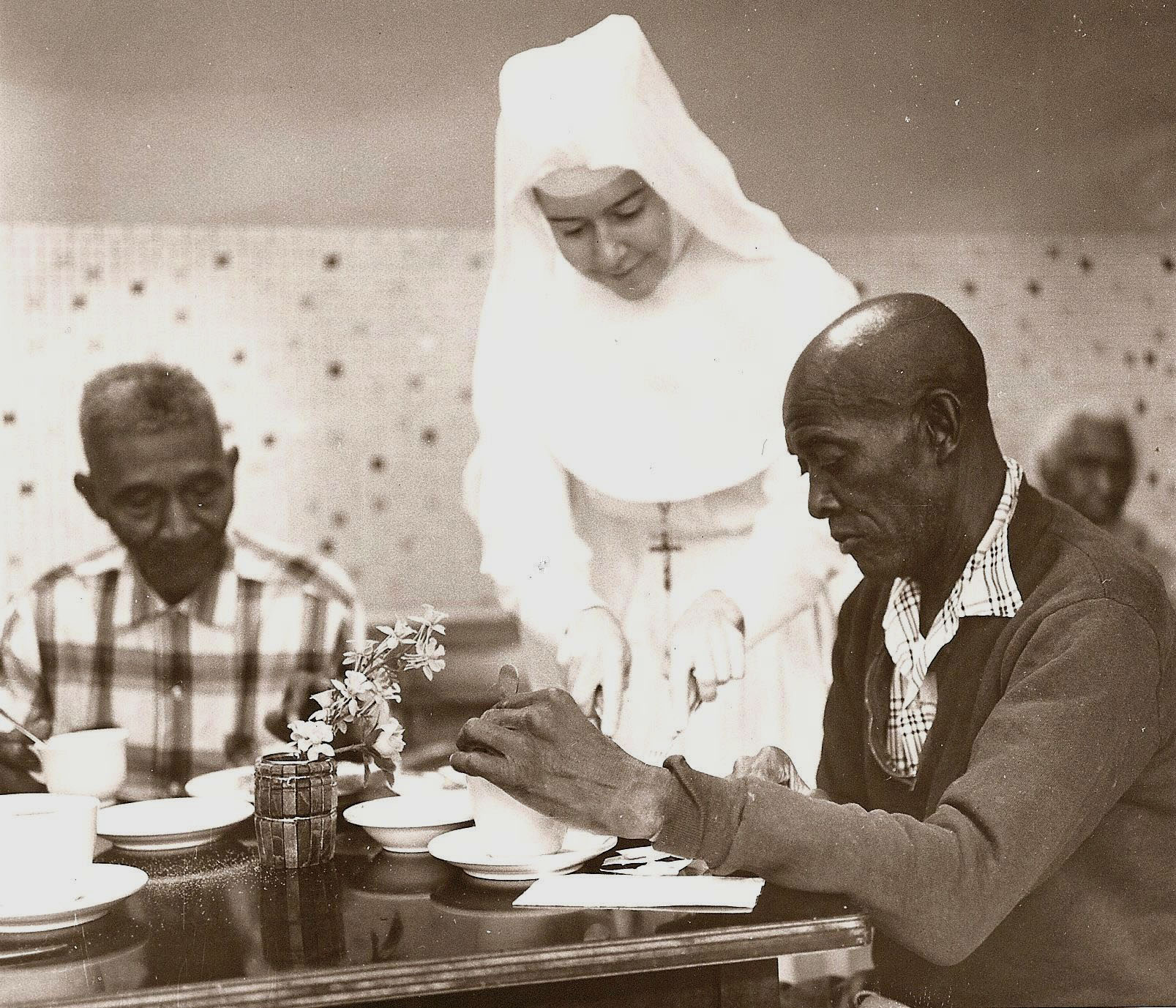

I was assigned there in 1959 by my community in Rochester, N.Y. I had made a retreat just before that and wanted to be very open-hearted. We didn’t have any mission except in Selma. I worked there as a nurse for nine years, which happened to be during the Civil Rights Movement. Good Samaritan Hospital was owned and sponsored by the Fathers of St. Edmond and staffed by us, the Sisters of St. Joseph.

What were segregation and the Civil Rights Movement like in Selma during the early 1960s?

There was total segregation. We served in the schools, convent and in the hospitals – those were our arenas – and church. The hospital we served at was the only hospital in nine counties that accepted blacks. People were very sick by the time they got there. We simply knew that the blacks were not being well treated and that segregation was something we had never experienced in the north.

Many of our hospital employees talked about the movement but were very fearful of physical violence. They were also fearful members of their families would lose their jobs if they were seen at a public demonstration. Fear had quite a claim on the people, which is one reason why the children went first – ‘We are paving our own way.’ Children from our schools went, and of course they came back and talked to the sisters about it.

How did you feel about being there?

It felt like it was important to be there. We were the hospital that took care of blacks. There were two other hospitals that took care of whites, and the white doctors owned them. The smaller of those two had a basement area that had 12 beds for blacks.

We also had the only vocational school of practical nursing that accepted blacks, so our program could be a huge economic opportunity, a huge step up for blacks, particularly women. We also had a number of men. The training provided them opportunity for employment, and later a number of them went on and got their degrees as registered nurses.

Did you participate in any demonstrations or marches?

Archbishop Thomas Joseph Toolen said that any priest or sister in the diocese who marched in the black community would be on the next bus out of Selma. I thought, ‘Well I wouldn’t be thinking of doing that,’ because I wanted to be in the hospital. I thought that was where we were called to be.

Others came from all over the country and marched. Fr. John Crowley, head of the Edmundite Mission, did not march but afterwards wrote an open letter to the Selma-Times Journal. The Edmundite priests didn’t march with the people, but they opened the rectory for meetings of the Black Voters League and people planning the marches.

Toolen was a good man caught in his time, caught in fear that Catholics were such a small percentage of the population. There is a place outside of Selma, called Orville, where the people had built a church with their own money; they had no debt. Once some black Catholics were coming down from Birmingham and stopped in Orville in time for Mass but were not allowed to come in to the church. When the Bishop heard that he said he would close the church. He took a stance there. But then later he did not take any – he took the stance of ‘stay out of it,’ so we were in the background.

As far as I was concerned, I could no longer think of leaving the hospital to go on a march or do anything like that – it felt very precarious in terms of our needing to be on deck at our best, given what was going on. This was a black hospital, and we did not need to have anything look like it was less than the best.

Do you have a story that really stands out in your memory?

Sadly, I only knew the Baptist Dcn. Jimmie Lee Jackson as a patient. Jackson was shot in Marion, Ala., about 33 miles northwest of Selma (Feb. 18, 1965). He was brought to Good Samaritan.

The morning after Mr. Jackson was admitted, the staff told me he had been at a night march for voting rights in Marion and was shot by a state trooper while trying to protect his grandfather. When I made my rounds to our patients and introduced myself to him, he took my hand and said, ‘Sister, don’t you think this is a high price to pay for freedom?’

Each of the next three or so days when I went to see him, he repeated that question, always taking my hand in his.

The last day I saw him, he was clearly taking a turn for the worse, and despite our efforts to turn his decline around, he died the following day.

His words and the gentle but insistent way he framed his question have stayed with me for almost 50 years. And, yes, then and now, I still think that was a very high price for a United States citizen to pay for freedom because of the color of his skin.

At his bedside, his family had placed his high school graduation picture in cap and gown.

Have you been back to Selma since you left?

I left Selma in 1968. It was hard to leave. I cared about people and felt they were my friends. I had loved them. I did go back about a year ago. There is a Martin Luther King Boulevard with a Civil Rights memorial, and the mayor of Selma is black. In Selma itself you can see the most amazing changes had taken places, but I don’t think the social barriers have been erased, even though there is more political involvement. The cultural differences are still there.

[Colleen Dunne is a Bertelsen intern in editorial and marketing and a primary contributor to Global Sisters Report.]