Jennifer Vale didn't realize she was capable of joining a university class discussion until she sat in on a lecture 10 years ago by a sociology professor with a story like hers: She overcame poverty to become a university graduate.

That professor-turned-mentor encouraged Vale to apply to Brescia University College, but provincial policies dictate that Vale would lose her welfare benefits if she received student loans.

A single mom with a then-9-year-old son, Vale relied on Ontario Works to put food on their table. Even without formal higher education, the then-28-year-old knew the system that held her back from receiving an education wasn't fair.

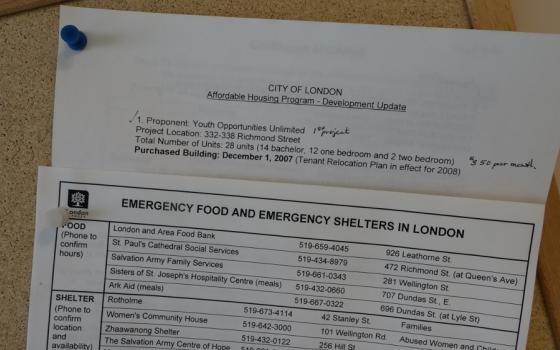

Around the same time in 2007, London's Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada also saw the injustice and found a policy loophole that allowed religious institutions to fund a student's university or college studies as the recipient continues to receive public assistance.

St. Joseph Sr. Joan Atkinson said the sisters sold a building in London they used as a transitional house for women and used the funds from that sale to set up a bursary for single moms on welfare who wanted higher education.

Atkinson and her colleague, Sr. Sue Wilson, keep track of the women who receive funding and turn their stories and successes into data for their Office for Systemic Justice, which they founded in 2000.

The women research major social issues — poverty, climate change and the environment, human trafficking, indigenous rights, refugees, immigration, etc. — and advocate for policies to improve communities globally. They start with a hyperlocal focus: seeking better education opportunities for women like Vale, working toward alleviating precarious employment, reducing poverty, encouraging improvements in mental health care, and more.

Vale applied and was accepted to Brescia for the fall of 2008. After she found out about the bursary from her Ontario Works case worker, she became one of the first to receive the sisters' funding for university while still receiving welfare. She's now a university-educated nonprofit leader and will start taking classes toward a master's degree this fall.

"This hasn't just impacted me. This has impacted the next generation of my family," Vale said. "This has impacted my son and his kids. Access to that higher learning shifted my thinking, shifted my actions, shifted my goals, and doing so, shifted the attitudes in my house and the conversations in my house, which created a kid who is a critical thinker, who is able to look at the bigger picture. It's incredible."

In the last 10 years, Atkinson and Wilson have provided scholarships to about 30 women who have since graduated from Brescia or Fanshawe College and found employment. With that experience, the sisters can tell provincial politicians, "Look, this does make a difference."

The sisters "have power, they have influence, and people listen to them," Vale said. "They absolutely must take [our stories] and they must do something with it, because that was not easy."

Through their systemic justice work, the sisters are often on the phone with community centers, social agencies and individuals, gathering information about various social services, creating research banks, and using data to urge policymakers to change laws, budgets and social programs to provide better access to financial assistance and opportunities to those who need it most.

"We've been told that we come in and we do it differently because, No. 1, we're not talking about issues that directly affect us," Wilson said.

To have multiple projects on the go at one time, the women work with other local groups seeking social change, like the London Poverty Research Centre, or others on provincial or national levels, like Citizens for Public Justice or Campaign 2000.

"We try to collaborate and build on the strengths of each group so that in the end, you have a stronger position to present, whether it's to politicians in our own country or on an international level," Atkinson said.

The center has become a platform to draw the community into conversations. Isabel Zucchero of the London Poverty Research Centre said Wilson is a "champion" of using lived experiences to improve local services for the most vulnerable.

"People are sitting around boardrooms talking about this stuff," Zucchero said. "[Wilson] really wants people who have lived in experiences, where they're using the food bank, they're going to women's shelters or who have been homeless before, people who have direct experience in poverty. [She's] bringing those people to the table ... when we're talking about translating into policy change or into effective initiatives in the community."

Wilson knows it's a long game. Discussions derived from their research about any given social issue may go on for years before an opportunity for policy change arises.

Sharing insights from individuals through media and public events allows others to join the conversations, magnifying concerns for politicians and decision-makers.

"They're a vital voice in the community," said Member of Parliament Peter Fragiskatos of London North Centre. Fragiskatos told Global Sisters Report that the sisters' decades-long advocacy work in education and health care stands out, adding that his recent interactions with them revolved around their advocacy for welcoming Syrian refugees to Canada.

"We took our cue from [the Sisters of St. Joseph and other groups] who are calling on Canada to do more: to step up, to live up to its international responsibility, and welcome people fleeing terror, fleeing war, fleeing the worst of conditions," Fragiskatos said.

"They are putting their finger on the pulse of the community and its needs," he said.

Translating direct outreach to advocating for change

Without a lot of "feet on the ground" to speak up for justice issues or humanitarian matters, the sisters had to think of new ways to meet needs they saw.

"If you look at our history, a lot of the response has been direct outreach to people living in poverty or living on the edges, and I think when we ran institutions, it was easier to deal with the systemic issues that went along with that," Wilson said. "But now that we're no longer running institutions, our efforts to get at the systemic issues, to get at the root causes and the policies that are affecting people, [we] have had to take a different route, and this is the route."

As the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada age, many sisters have retired, leaving vacant high-level roles at their institutions: principals, superintendents, hospital administrators. For example, the sisters founded London's St. Joseph Hospital in 1888, but gave it to another governing body in 1993.

Wilson attributes the office's recent successes to generations of sisters before her who often directed policy conversations from their positions and became reliable and respected voices.

"They've built up institutions in the city. They've had a huge impact," she said. "In many ways, their work has opened all kinds of doors for us in this work."

The Congregations of St. Joseph, the sisters' nongovernmental organization at the United Nations, allows Atkinson and Wilson, along with sisters from the United States, India, Australia, Algeria, Argentina and across Europe, access to the global gathering of the U.N., including important meetings and works of various commissions.

"We're trying to use the leverage we have as an NGO at the U.N. to gather the voices of our women in many, many countries around the world around some of the social and economic issues that are impacting their lives," Atkinson said.

The duo describes the global effort as another way to influence national and local policy. Working on grassroots problems in Canada, they can show local politicians policies adopted at the U.N. and ask how Canada will meet those goals at home.

After Canada initially voted against the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People in 2007, sisters joined indigenous groups and other social justice groups to pressure Canadian leadership to endorse it by 2010. Wilson said they continue to remind lawmakers to back up their signatures with tangible implementation strategies to make sure action is taken on local levels.

Sharing narratives and changing policy

Wilson, who grew up in an economically poor family, understands the plight of too many in her London community. She traveled to South America as a sister and later saw hungry children in her own classrooms as a teacher in London, which drew her into justice advocacy.

Atkinson's perspective broadened when she took her high school students to Northern Ontario to facilitate a summer program for indigenous students in remote areas and saw serious social issues affect families' lives.

"Those kinds of things opened your eyes to what's happening, in particular some of the more remote, far-away indigenous communities and why some of the social issues that affect family life happen," Atkinson said. "You kind of saw it up close and personal through those experiences. That kind of changed me, too."

Wilson bases some of her lobbying efforts around narratives of real people she meets as chair of a local anti-human-trafficking coalition.

One woman's story helped Wilson and her colleagues persuade Parliament to change the law regarding temporary resident permits. With a work permit for exotic dancing, the woman, who had been trafficked from Eastern Europe, could not seek other employment because of visa restrictions at the time.

Wilson said the woman's experience was quoted in Parliament's final report of the Status of Women Standing Committee, which eventually changed a law in 2007 to rework the conditions of temporary resident permits. The woman now has Canadian permanent residency.

"That was not just us having an impact, but we can go back to this woman and say, 'Wow, thank you for allowing us to tell your story because here's the impact,' " Wilson said.

After lobbying around poverty issues, Wilson said she is pleased the province of Ontario adopted a poverty reduction strategy in 2008 and added another in 2014, aiming to reduce poverty by 25 percent.

"That was one of those moments where, 'Wow! It worked!' " she said. While the poverty rate has not yet dropped by 25 percent, Wilson said it has declined, and through the strategy came the Canada Child Benefit, a monthly stipend for lower-income parents. The benefit, according to Wilson, "has been a game-changer for a lot of families."

The strategy, though, still leaves many behind.

"The changes aren't night-and-day kind of changes, but they're one step at a time, and I think that's all we can ask for," Wilson said. "Really, even if we weren't doing it, we would have to try, just because it's the right thing to do. If it weren't working, we would try other methods, but we would still be trying."

[Dana Wachter is a freelance journalist and digital storyteller based in London, Ontario.]