Ask Sr. Mary Johnson to draw a picture of a successful religious institute 20 years out. She doesn’t mention whether it’s liberal or conservative, where it is, how big it is, how old its members are or what they are wearing.

In her picture, it’s the connecting that matters.

Successful institutes, Johnson said in an interview, will have broad and deep networks that allow them to respond to the needs of the local and the global church. Ministries to young adults and teenagers and ministries to the wider population will reinforce each other and keep charisms fresh and relevant.

“I like to quote Teilhard de Chardin when he says, ‘The future belongs to those who give the next generation reason to hope,’” Johnson said, going on to describe “hopefully a vibrant mix across generations that will enhance the mission of that organization and lead it into a future.”

“So that, to me, is the driver, Johnson continued, “and everything else, in terms of symbol, in terms of structure, comes from the organization being in touch with the new generations around it and their hopes. The communities (religious institutes or congregations)* that are intergenerational will go forward, and the communities that are in touch with the hopes and desires of a new generation around them will be able to attract new members.”

Unlike some predictions about the future of religious life, Johnson’s vision flows from statistical analysis. Relying on two major studies of women religious conducted 10 years apart, Johnson, along with Sr. Patricia Wittberg and Mary Gautier, look at the experiences of women who entered religious life in the United States after 1965 in a new book, New Generations of Catholic Sisters: The Challenge of Diversity. (Oxford University Press, 2014; $29.95)

Johnson is a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur and professor of sociology and religious studies at Trinity Washington University. Her co-authors are Patricia Wittberg, a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati and professor of sociology at Indiana University-Purdue University, and Mary Gautier, senior research associate at the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University (CARA).

At 141 pages of text (with some 60 more in research sources, references and the two surveys themselves) New Generations is both focused and compact. But spinning off its statistical analysis are conversation-starters for at least a month of Sundays:

- How has the appeal of religious life in the United States changed over generations of women?

- What does religious life offer millennial Catholic women, who are less connected to the church than earlier generations?

- Can a religious institute articulate and maintain a distinct identity that also speaks to changing world-views among 21st century generations?

Keep going.

The authors carefully present more detail than can be easily summarized, on findings as precise as the generational appeal of daily Eucharist compared to Liturgy of the Hours and as broad as the revitalizing influence of religious institutes over centuries.

But I found three areas especially telling.

First, the authors describe a number of explanations given for the predicted demise of religious institutes (which are also known as religious orders and congregations). They then lay out basic, statistical findings about vocations in the United States, which include:

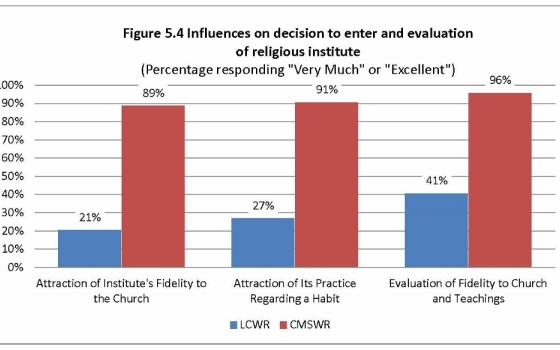

- More than 1,200 women are in formation in religious institutes and monasteries, split almost evenly between communities associated with the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and with the more traditional Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious.

- The age-range of new members associated with each conference is quite different: More than 50 percent of new CMSWR institute members are in their 20s; more than 50 percent of new LCWR members are over 40.

- Most institutes in either conference have no new members. The average number of new entrants to LCWR institutes is one, according to Georgetown’s CARA. For CMSWR institutes, the average is four.

- More than nine out of 10 religious sisters in the United States are described as white and non Hispanic/Latina. In contrast, 42 percent of those in initial formation are women of color, resembling “the youngest generation of the church.”

An important message may be tied to that last statistic.

"The new sisters look like the new church, and I think that is the key finding,” Johnson said. “The demographic diversity of the new generations of sisters matches to a good degree the demographic diversity of the church in the United States today."

I asked: Is that heartening?

"It is heartening because those generations of sisters will be able to minister to old and new populations in a variety of ways, and they will be able to respond to a variety of old and new needs."

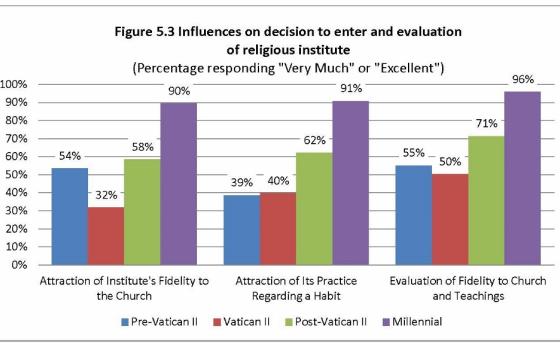

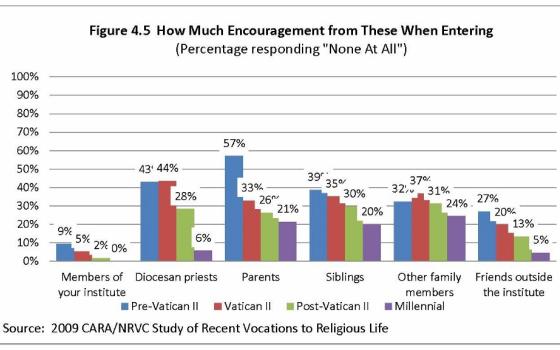

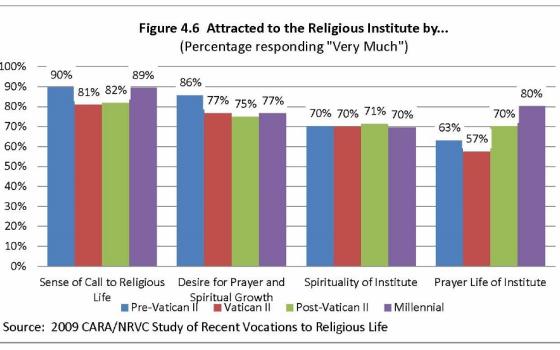

In a second telling area, the authors analyze generations of Catholics, broken out in four distinct groups:

- The Pre-Vatican generation, born before 1943, raised in a church that was “an unchanging anchor” for whom the Second Vatican Council was either a “welcome liberation” or a “threatening disruption”

- The Vatican II generation, born between 1943 and 1960, who welcomed the changes experienced in their younger years

- The post-Vatican II generation, born between 1961 and 1981, for whom the church “was often in constant and disorienting flux”

- Millennials, born since 1982, more trusting of the church than the two previous generations but also the “least knowledgeable about Catholicism’’

Between 1987 and 2011, the percent of U.S. Catholics in the two older generations dropped from 78 percent to 43 percent. And looking at younger generations, the authors note that that 70 percent of Catholics in 2011 were in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

Among other differences, young adult Catholics are less likely to “accept the Church’s teaching authority on moral issues such as divorce, contraception, abortion, homosexuality and nonmarital sex” or value a celibate clergy, attend Mass regularly or engage with parishes.

The analysis highlights another trend, first seen in Wittberg’s earlier research.

"Regarding the 90 percent of Millennial women who are emphatically not interested in traditionalist religious life, a lot have left Catholicism altogether,” Wittberg said in an interview. “This is the first generation for whom there are fewer women than men interested in remaining in the Catholic church, or in serving as vowed religious. I can't emphasize how ominous this is.”

A third area looks at how to connect religious life to younger women. Given that they are less connected to the church, what does religious life offer?

“What I would hope,” Wittberg continued, “is that versions of religious life could develop and thrive that would offer Millennials a sense of community and contemplation. They do seem to want community and contemplation, which might keep them in the Catholic church. For Post-Millennials, It may be too early to tell what they want, but there is a growing sense of the problem of increasing class inequality in the U.S., so service to the poor may attract them."

And how can institutes connect to young women who do say they have thought about religious life? A 2012 CARA study reported that eight percent of Millennial women considered a vocation at least “a little seriously.”

The authors’ suggestions cover a lot of ground. Create more opportunities for women of different generations to get to know each other. Get better at inviting women to religious life. Encourage institute members “to articulate a charism that provides a sufficiently distinctive group identity but is also sufficiently encompassing to appeal to a wide range of potential entrants” and still maintain unity among members.

New Generations of Catholic Sisters holds a lot of warnings around demographic trends and reports that “. . . the future of religious life in the United States would appear to be in peril – unless concerted efforts are made to reach out to those who, surveys tell us, have considered religious life but did not choose to enter it.”

Still, Mary Gautier, from CARA, has another message.

“The primary thing we would like people to take from this book,” Gautier said in an email, “is the realization that religious life is not going away, but it is transforming. The Holy Spirit continues to call women to religious life, and the women who are attracted to religious life are responding to the prayer life, the community life, and the ministry, just as the generations who have responded to that call in the past did.”

*Clarification: By "communities" Mary Johnson specifically means a religious institute or congregation.

[Mary Lou Nolan is managing editor for Global Sisters Report.]