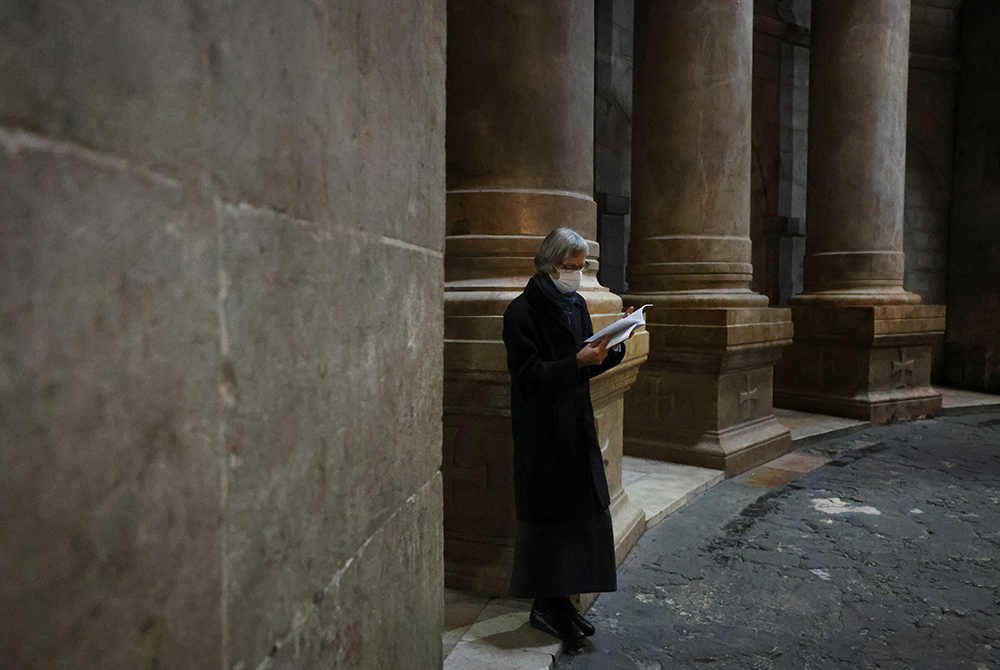

A worshipper wears a face mask to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on Holy Thursday in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem's Old City April 1. This year, Joan Chittister celebrated Palm Sunday in a monastery still under a form of COVID-19 lockdown. She called it "the most beautiful, impacting Palm Sunday I had ever seen." (CNS/Ammar Awad, Reuters)

Sunday, March 28, was Passion Sunday — Palm Sunday we call it now, in this era. Whatever generation you are, however you name it, this Sunday marks the opening of Holy Week. It is a liturgical narrative of the acme of the life of Jesus and his journey from the Galilee to the cross.

It reminded us of that life of mystery and mystique. How Jesus got from a place of total adulation to total rejection — to the passion — was very hard to explain. But that was all right. We simply listened to the readings and went from one event to another till the long week ended in alleluias and jubilation.

COVID-19 changed that now. And the question is: "to what effect?"

Well, here at the monastery, at least, this introduction to Easter was the most beautiful, impacting Palm Sunday I had ever seen. Somehow or other, I had been made a part of it rather than a mere observer, listener, passerby.

Our monastery, of course, is still in a reduced form of COVID-19 lockdown — meaning no one other than the sisters themselves are in chapel now for the Hours of Liturgical Prayer. Under normal conditions, oblates, friends, even guests from across the country, would be with us for it. The week would be a picture of the Christian community — priest, religious, laity — on pilgrimage to the bedrock of the church and the core of the Christian faith. It would be something we watch and hear and remember from years past.

But even alone in the monastery chapel here and now, the concentration on one small segment of the Gospel took on special meaning. It was not a reiteration of a set of rubrics we had witnessed over and over from one year to another. Suddenly, this story became our story. It was the story of our own lives as Christians in the world rather than simply Christians in the church.

It is, I realized in a different way this year, an important distinction.

Even more significant, if your spiritual life was formed before the Second Vatican Council in 1962, before the shrinking of the culture of Catholic schools, daily Mass, Friday Stations of the Cross during Lent and CCD classes — which were all thriving parts of the spiritual psyche — it could seem like another world now. And in a sense, it is.

The impact of all those differences is not only life-changing as far as the way the faith is lived. It is, in fact, a new way to see what it means to live the faith at all. If you are a pre-Vatican II Catholic, you were hardly more than 14 years old by the time you had been schooled to see Holy Week as a kind of memorial service embedded in the Mass. All of the readings, all of the hymns, all of the prayers are in your DNA. It's what we did. All the time. Every year. Over and over again. It was right and eternal and wrapped up and finished. But not now. And definitely not this year. Not in our own monastery chapel.

Then, it was a system repeated over and over again. Now it is a moment to compare myself and my life in my time to the life of Jesus in his own time.

This year, we were not simply repeating the rubrics of the church. We were embedding ourselves, our lives now in this country at this time in a story that was itself eternal, yes, but not simply replicated. Lived.

The Jewish narrative of Passover reminds the Jewish community that YHWH has saved them and will go on saving them. So, too, the Christian narrative that is the basis of Palm Sunday's liturgy remembers that Jesus paid the ultimate price for choosing the needs of the people over the dictums of the authorities. Jesus lived on in the hearts and minds of the people who knew that the higher value is love for one another rather than institutional laws.

It was that narrative that turned Palm Sunday at the monastery into the parallel between the life and suffering of Jesus then and the lives and sufferings of people today who are also being forgotten and ignored by today's authorities.

Remembering that Jesus was a threat to the systems of first century Israel, it is obvious that Christianity today, thanks to Pope Leo XIII's encyclical Rerum Novarum and the social teachings of the church that follow it, also threatens the social system as we know it. We know that the needs of too many are also being overlooked now. And here. We want the obvious problems to be recognized as a Christian imperative.

And so, Palm Sunday liturgy at the monastery became a whole new awareness beyond the rubrics and outside of the Mass. It was embedded in the Gospel we use as a guide to determine the way we live our own lives now.

Now it's about us and the needy and Jesus — not about the Catholic organization and the system and Jesus. We have to make it real.

So, the community liturgy called out the situation of immigrants who walk thousands of miles for safety but are then being left unattended at the gates of our country. We noted that poor families in the United States of America can no longer afford to eat three times a day — and cited that in the liturgy. We followed Jesus and the disciples as they ate their last supper together — and ourselves tasted the pain of it and the story under the story that it made us see.

We remembered that the apostles slept unconscious of what was happening to the world around them, as we ourselves so often do. We know that people have become homeless, been evicted even, for failing to pay rent or meet mortgages in the United States, the wealthiest country in the world. We mourned the fact that this country prefers a minimum wage to a living wage for people who must then work two jobs to maintain families hanging by a financial thread.

These — and more — are also being crucified in this day and age as the wealth gap widens and moving from the lower class to the working class and the middle class becomes more and more difficult. Let alone to any degree of genuine financial independence and security at all.

But what is also being demonstrated here is the difference between religion and faith. Between the role of the church as an institution and the place of the faith in the life of the seeker. The institution clearly can only carry us so far into faith. The rest of our souls we must attend to ourselves.

At the end of the day, it is not the presence of clergy that determines the impact of the Gospel. It is not the canonicity of the rituals that define their spiritual value. It is not the present translation or the traditional format of ancient prayers that govern our lives as Christians in the world.

Advertisement

And it is definitely not a return to medieval vestments, European birettas and cassocks or collars to declare the ontological predominance of priests — favored by some younger priests, these days, we're told — that will make the church, church. Going back to a period where priests were better educated than the laity and so the last word on everything did not before and will clearly not now certify the quality and character of our Catholicity.

In fact, a by-product of COVID-19 — the lockdowns — make some astounding spiritual truths clear: No priest has celebrated a Mass in our monastery or led any rubric of the church there for over a year. Yet, the power of the prayer, the beauty of its pace and depth, the personal impact of the six scenes of Palm Sunday and the profound engrossment of every person there felt sharper, clearer, more personal than ever before. Or to put it another way, what the "tradition" imparted to us, came alive in our own age, our own way.

It seems that the church — clerical, lay, elderly and young — who for far too long considered themselves spiritual children in need of parental direction, are all growing up. Faith, we are learning the hard way, is not assured by a repetition of old forms.

The reality, I repeat, is this: The institution can only carry us so far. The rest of the journey is up to us to make out of its everlasting truths, not the mere repetition of old patterns done in old ways. We need to understand that now it's about us and the needy and Jesus — not about the Catholic organization and the system and Jesus. We have to make it real.

Amma Syncletica, the fourth century Desert Mother said: "In the beginning there is struggle. ... But after that there is indescribable joy. It is just like building a fire: at first it is smoky and your eyes water, but later you get the desired result."

From where I stand, the lockdowns of COVID-19 didn't deprive us of anything in the realm of faith. Instead, they are simply requiring us to dig deeper for spirituality ourselves — which is what we have always been meant to do but have allowed the institution to do for us.