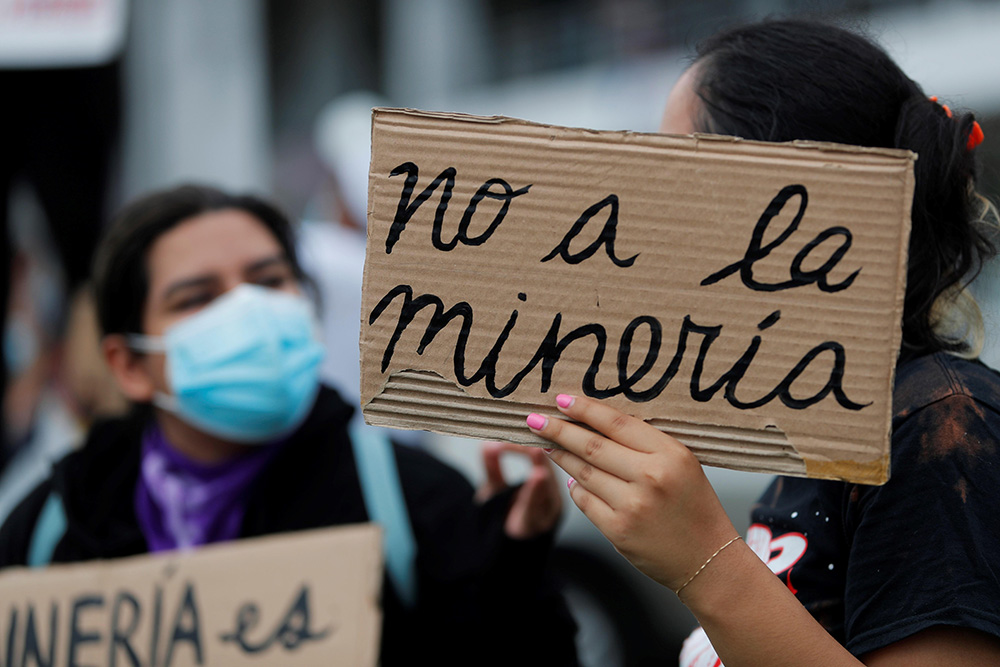

Environmental activists demonstrate in front of the Ministry of Commerce and Industries of Panama in Panama City May 25, protesting a government plan to expand mining. (Newscom/EFE/Bienvenido Velasco)

Three dozen church groups in Panama have issued a statement protesting a plan to permit new mining in a forested area near Indigenous communities and have called for the government to protect the rights and ensure the participation of communities affected by development projects.

"Panama is a small country with very fragile ecosystems, so it is necessary to lay the groundwork for a green economy and circular production that benefits everyone along with the environment," the groups said in the statement released June 5, World Environment Day.

"In the context of Panama, mining destroys vast expanses of tropical forest," the statement added. "These damages are not offset by the planting of single crops in another place, just as single-crop plantations are not 'reforestation.' "

The statement was prompted by a May 12 government decree creating a 96.5-square-mile mining concession, an area where mining for metals will be permitted, in the provinces of Coclé and Colón, southwest of the Caribbean seaport of Colón, where a large open-pit copper mine already operates.

The new concession is part of a government effort to expand mining as a way of revitalizing Panama's economy after the pandemic, said Fr. Joseph Fitzgerald, a Vincentian missionary from Philadelphia who heads the Panamanian church's national Indigenous ministry.

One of the world's richest copper deposits lies under Panama's central mountain range, and there have been periodic efforts since the 1960s to expand mining in the country.

Ngäbe-Buglé people block the Pan-American Highway in El Vigui, Panama, on Feb. 4, 2012, to protest mining exploitation on their lands. (AP Photo/Arnulfo Franco)

Part of the copper deposit lies under the Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca, or Indigenous territory, where Fitzgerald is pastor of St. Vincent de Paul Parish in Soloy, ministering to about 200 scattered communities.

The government opened the area around the comarca to mining in 2010. In early 2012, protesters demanding a halt to the mining shut down the Pan-American Highway — the country's main commercial transport route — for five days. After two Ngäbe-Buglé men were killed in a police crackdown on the protesters, the government agreed to prohibit mining for metals in the comarca.

Nevertheless, Fitzgerald said, there is constant political pressure to lift the ban.

"It is technically off limits, but that doesn't bring it off the table for those who are looking to further mining," he told EarthBeat. "It's [seen] more like a short-term obstacle for the mining industry, and not a decision [by Indigenous communities] that they need to respect."

The current push to expand mining in the country is being spearheaded by the Ministry of Commerce and Industries, with support from the Inter-American Development Bank. The ministry is conducting virtual dialogues about the process, but has not included the communities that would be affected, Fitzgerald said.

"Since February, all of a sudden, it's a central news piece again," but because of Panama's fragile ecosystem, "it's just a horrible context to put mining into," he said.

The country's regulations are also fragile. Several smaller mines have been abandoned in recent years, leaving the surrounding area polluted with mining waste.

"Panama doesn't have the capacity to respond to these situations, so when the company left, it was a disaster," the Vincentian priest said of the Molejón mine abandoned by Petaquilla Gold, a subsidiary of Canadian-based Petaquilla Minerals. The mine suspended operations in 2013 and was subsequently abandoned. In 2015, the Environment Ministry estimated that cleaning up the pollution there would cost $30 million.

Located on the land bridge between North and South America, Panama lies in the world's most biologically diverse region, according to the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity. The forested mountain range, which connects to Costa Rica, is part of an important corridor for wildlife.

"When you go up there, it's virgin forest," Fitzgerald said of the mountains. "From the top, you see both oceans — you see the Pacific on one side and the Caribbean [Sea] on the other side, and they both look [as if they are really] close, so you realize how small and fragile it is."

Advertisement

The terrain is very steep, and if the hillsides were stripped of trees, they would erode quickly. Although mining companies promise to offset deforestation by planting trees elsewhere in the country, "it ends up being tree farms" rather than true reforestation, Fitzgerald said.

The statement opposing the new mining concession was signed by various national and diocesan ministry offices, as well as religious congregations, universities and lay groups. The Panama Laudato Si' Movement and the Mesoamerican Ecological Ecclesial Network added their names, as did half a dozen nonreligious groups.

The groups demanded that the government suspend the new concession and to conduct a dialogue that includes all people affected by mining. They added that the government must not "dismiss the idea of a complete moratorium on mining at the end of the process."

The statement also calls for Panama to comply with the Escazú Agreement, which the country ratified in 2020. The pact, which went into effect on Earth Day, April 22, requires countries to ensure that communities affected by development projects take part in any decisions about those projects.

Archbishop José Domingo Ulloa Mendieta of Panama City echoed the groups' concern about mining and their demands in his homily at Mass on June 6, the feast of Corpus Christi.

"Now, more than ever, we must be united to care for our common home," he said. "It is the only inheritance that we can leave our children in a country where every citizen protects our land, water and forests. May it be the ethic of stewardship that guides politics in this country."