(Julie Lonneman)

Because most of history relies heavily on literary records written by men, discovering reliable historical data about Christian women can be challenging. This search is further complicated by the fact that Christianity has relied heavily, if not exclusively, on the written word as a primary means of understanding its own history. Information gleaned from visual artifacts (frescos, paintings, sarcophagi friezes) and material artifacts (jewelry, clothing, household items) has until recently been left almost exclusively to art historians and archaeologists. Although female patrons financially subsidized many male leaders in the early church (Phoebe, Lydia, Domitilla, Paula, Olympias), their presence is barely discernible in the literary sources. Scholars soon recognized that visual imagery and artifacts could provide information about women in the early church that was either not available or was sometimes distorted in the written history. This article discusses recent research into Christian funerary art and what it reveals about women and authority in the early church. Over the course of three centuries, official church documents justified curtailing female authority by repeating 1 Timothy's admonishment forbidding women to teach or have authority over men and requiring them to be silent in the assembly (1 Timothy 2:12). Yet Christian funerary art from the late third until the early fifth centuries depicts women teaching and preaching despite being told they should do neither.

Because of space considerations, only a brief discussion of this fascinating topic is possible here. A more detailed treatment may be found in my book: Crispina and Her Sisters: Women and Authority in Early Christianity (Fortress 2017).

Women and authority on Christian sarcophagi

Christianity spread rapidly throughout the Mediterranean world thanks to the many women and men — such as Prisca and Aquila, Paul, Junia and Andronicus, Lydia, Phoebe and others — who evangelized primarily via domestic and patronage networks. Greco-Roman culture was highly visual. Elegantly sculpted and painted statues, colorful mosaics, and graceful paintings embellished public baths, fountains, libraries, the walls and floors of shops, gymnasia, public arenas, temples and public buildings, as well as private homes and villas. This is the world in which Christians were born, grew up, lived, worked and died. Christians were part of their culture and their culture was part of them. It is therefore unsurprising that Christian burial customs and tomb art would reflect their Greco-Roman heritage. It would also reflect the transformative impact of their Christian beliefs.

For Romans, whether Christian or pagan, a sarcophagus was a monument filled with meaning, not just a container for a corpse. Only the wealthy could afford such a commemoration, and planning for how one wished to be remembered was an important process. Being portrayed with a scroll, capsa (basket for scrolls), or codex (book) was an instant indicator of the deceased's learning, status and wealth. Roman funerary art was meant to construct the idea or the identity of deceased persons and commemorate their values and virtues. Christians adopted and adapted the iconography of their Roman culture in commemorating the deceased with speech gestures, scrolls, capses, codices and in orans (prayer) postures. Both Christian women and men were commemorated and idealized as persons of status, authority, learnedness and religious devotion. When — as often happened — the deceased's funerary portrait was depicted with a scroll or capsa in close proximity to biblical scenes, it also signaled learnedness about the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. What follows is a brief overview of my recent study of funerary portraits on Christian sarcophagi.

Conducted over a three-year period, this original research analyzed 2,119 images and descriptors of third- to early fifth-century sarcophagi and fragments, which comprise all publicly available images of Christian sarcophagi. Comprehensive examination and analysis yielded 247 sarcophagus artifacts containing 312 Christian portraits of deceased women, men, couples and children. (Some sarcophagi had more than one portrait.) An important finding was that of the 203 solo/individual portraits, 156 were of adult women compared to just 47 of adult men. The statistical likelihood that this is due to chance is 1 in 1,000. An earlier study of portraits on non-Christian sarcophagi had found equal numbers of solo male and female representations. The preponderance of solo female portraits on Christian sarcophagi strongly supports contemporary sociological and literary scholars who theorize that early Christian women were of higher status than Christian men.

An examination of solo male and solo female portraits with motifs of learnedness, influence and authority such as scrolls, capses, codices and speech gestures found no statistically significant differences between groups. Numerous sarcophagus reliefs of women surrounded by biblical scenes, with hands in a speech gesture and holding scrolls, offer a poignant and powerful witness that male admonitions to be silent were not heeded. The prevalence of these motifs suggests the emergence of a new female identity of biblical learnedness and teaching authority. Scroll-speech iconography would come to have enduring significance in church history into the present day. A photograph of a stained-glass window in a contemporary Catholic church in Cleveland, Ohio, exemplifies the authoritative status this iconography would come to represent (see photo above).

Solo female portraits were 2.6 times as likely as solo male portraits to be depicted in an orans-only posture (without accompanying capsa). The difference is unsurprising, however, because the Christian orans iconography actually derived in part from the Roman muse figure, which was always female. For centuries, and even today, numerous interpreters viewed orans figures as symbols of the soul rather than representing an actual deceased person. This perspective meant that Christian women who chose an orans for their funerary commemorations became essentially invisible. Recent investigators have shown unequivocally, however, that there are portrait features on Christian orans figures gracing sarcophagi. Far from being disembodied "souls," contemporary interpreters now understand portrait orans as representations of the deceased, and as such, they symbolize the values and virtues with which the departed identified.

In-facing "apostle" figures on portraits of the deceased have been variously interpreted as saints, apostles or angels who accompany the soul of the deceased into the afterlife or as "effective space fillers" and "reverential supporters." But since these in-facing "apostle" figures are even more prevalent on Christ reliefs, such interpretations are incomplete at best. (In my review, Christ is shown 166 times with in-facing "apostles," compared with 73 depictions on solo female portraits and 10 on solo male portraits.) Surely, Christ does not need accompanying into the afterlife. Experts in non-Christian funerary art believe a sculpted portrait portrayal on a third-century "philosopher's sarcophagus" became the model for how Christians later represented Christ's authority. The in-facing "apostles" flanking Christ draw attention to the central figure and point to his status as one with authority (see cover photo). A central thesis of my research is that that in-facing "apostle" motifs function similarly on portraits of deceased Christians to enhance their significance and authority. In my study, solo female portraits were 2.2 times as likely as solo male portraits to contain in-facing "apostle" figures. The likelihood that this finding is due to chance is 2 in 1,000. If one subscribes to the notion that the in-facing "apostles" were meant to accompany deceased Christians into the next life, it is odd that so few men chose this iconography.

A plausible explanation of its popularity with early Christian women is that it served to validate female religious authority at a time when churchmen were silencing women in the Christian assembly. Who better to affirm a woman's ecclesial authority than Peter and Paul, the founders of the church of Rome? In summary, the most popular female self-representations on Christian sarcophagi were in-facing "apostle" configurations, the orans figure and other "learned woman" motifs, such as portrayals with a scroll or codex and/or a capsa. While early Christian church treatises such as the Apostolic Tradition, the Didascalia Apostolorum and the Apostolic Constitution, give a largely negative witness about women who exercised authority, archaeology suggests that many early Christian women were remembered for exercising it — with its corresponding status and power — or these iconic authority motifs would not have been chosen to signify the female role models idealized by early Christians.

Advertisement

Corroboration from writings about fourth century women

There is remarkable corroboration in fourth century literary sources for what this study posits about the women whose portraits were found on Christian sarcophagi. They were well-educated, wealthy, wives, mothers, and — judging from the number of solo female portraits — single women or widows. Their funerary iconography indicates that (at the least) they proclaimed or taught Scripture. That these fourth century "tomb women" exercised significant ecclesial authority is bolstered by evidence from contemporaneous writings and inscriptions indicating that some women exercised governance, serving as enrolled widows, deacons, heads of monasteries and presbyters. In most instances, such women governed other women, although there are significant exceptions such as the deacon Marthana in Seleucia (Turkey), who governed a double monastery at the martyrium of Saint Thecla. When Jerome left Rome for Bethlehem, the priests of Rome turned to Marcella for clarification of biblical texts. Melania the Elder's ecclesial authority publicly reconciled 400 schismatic monks. Her spiritual wisdom and authority led to the healing of the renowned monastic writer Evagrius. Melania the Younger's ecclesial authority publicly countered Nestorianism at the court in Constantinople. Proba's literary and biblical authority created a remarkably effective cross-cultural evangelizing tool that would influence Christian men and women for generations.

These "mothers of the church" exercised authority at a time when "fathers of the church" forbade women to speak or teach publicly, preferred that women stay at home, and judged women more susceptible to "heresy" than men. Yet Christian women spoke up about important ecclesial issues, taught both men and women, and witnessed freely about the Christ with whom they had thrown in their lot. Findings from archaeology confirm what contemporary scholars such as Carolyn Osiek and Peter Lampe had previously hypothesized that women were considerably more influential in early Christianity than is generally recognized. While men predominate in the literary record, funerary portraits point to a preponderance of Christian women who were remembered as exercising ecclesial authority.

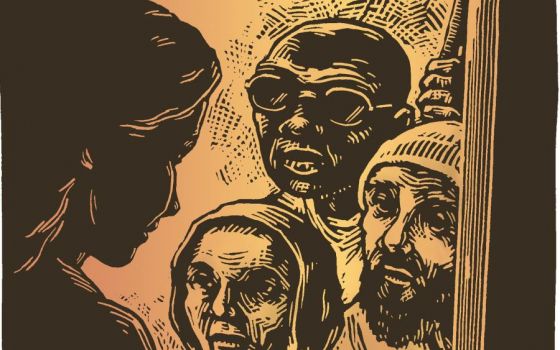

One could reasonably ask from whence came the strength and inner authority that impelled women of the early church to disregard male leaders who attempted to suppress their voices. I suggest that what led women to speak rather than to be silent was their faith experience in the risen Christ. Let us examine one sarcophagus that suggests what at least one Christian woman (we will call her "Junia") understood to be the source of her inner authority. In the center of the figure below and on the top of page 4, Junia holds a codex in her left hand while her right hand is shown with a speech gesture. Arrayed on both sides are biblical scenes, including (left to right) God the Father with Cain and Abel, Christ with Adam and Eve, healing of the paralytic, healing of the blind, miracle at Cana and healing of Lazarus. Several years before she died, Junia, or her family, commissioned this uniquely sculpted sarcophagus to memorialize her and the values that shaped her identity. When Junia died, her sarcophagus was delivered to her home, where she would lie in state for up to seven days so family members, clients and friends could pay their respects and gaze upon her carefully carved memorial. They entered a liminal space to reflect upon her life, her values, her beliefs and, inevitably, the meaning of life and death.

Janet Tulloch, a specialist in early Christian images, has observed that ancient art was viewed as social discourse meant to "draw the viewer in as a participant" and that art was understood "to perform meaning(s), not simply embed them." Using Tulloch's criteria, it is plausible that Junia wished her loved ones to enter into a liminal space and experience Christ's power to reverse the effects of the fall from paradise — namely, healing the blind and lame, providing an abundance of wine in the new reign of God, and raising Lazarus (and Junia) from the dead. Where did Junia find her authority to witness and teach about Christ? A hint is found in a close-up of her face that has been carefully sculpted close to the face of Christ who leans in, with mouth open, as if to whisper in her ear. Junia and her family wished her to be remembered as someone who taught with the authority of Christ. Her mourners commune not only with the departed Junia but also with the Christ who heals and raises up through the meaning evoked and "performed" by the art on her sarcophagus. Junia exhorts the living to embrace the Christ who authorized her ministry and to whom she witnesses from beyond the grave. She joins a sisterhood of Christian women, past and present, who obey an authority that supersedes any who would silence them. Junia is one of countless women who witness that they are made in God's image and called to serve in persona Christi.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the June 2019 issue of Celebration.