(Julie Lonneman)

After years of abandoning the practice, many Catholic parishes once again offer regular opportunities for eucharistic adoration. While some enthusiastically embrace this practice, others associate it with unappealing aspects of pre-Vatican II piety. In a time when the centrality of the Mass has been recovered and frequent Communion is the norm, how might Catholics of the new millennium approach eucharistic adoration?

One possible approach may be gleaned from the apostolic letter Pope John Paul II wrote in October 2004 to announce the Year of the Eucharist. Called Mane Vobiscum (Latin for "stay with us"), this letter, at one point, asks us to reverse our usual way of looking at things: "We are constantly tempted to reduce the Eucharist to our own dimensions," says John Paul II, "while in reality it is we who must open ourselves up to the dimensions of the Mystery" (n. 14).

Usually, if we want to understand or contemplate something, we might imagine ourselves holding it as an object out in front of us, looking at it, observing it, admiring it, trying to learn about it from studying it. Here the late pope challenged us to turn this process around. Rather than submitting the Eucharist to our scrutiny or examination, the late pope wanted the Eucharist to scrutinize us. Instead of holding the Eucharist before us to probe its meaning, we place ourselves before the Eucharist and let it probe us, telling us our meaning. Surrendering ourselves, we "open up" to the mystery that is the Eucharist.

What would it mean to understand eucharistic adoration in this way?

The Mass comes first

When we "open ourselves up to the Mystery," eucharistic adoration will always turn us toward the actual celebration of the Eucharist, as the church's liturgical documents emphasize repeatedly. Eucharistic adoration, in Catholic teaching, is always secondary to the Mass.

Since "[t]he celebration of the Eucharist is the center of the entire Christian life" (n. 1), the ritual book Holy Communion and the Worship of the Eucharist outside Mass affirms that "The celebration of the Eucharist in the sacrifice of the Mass is the true origin and purpose of the worship shown to the Eucharist outside Mass" (n. 2, emphasis added). Eucharistic adoration both comes from the Mass (its "origin") and leads to Mass (its "purpose").

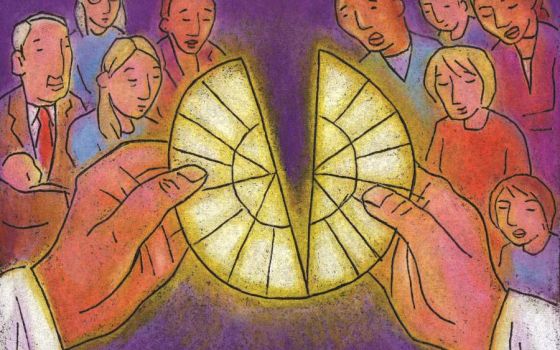

Sometimes in our history, however, Christ's presence in the reserved sacrament seemed to overshadow the Mass itself, as if Mass were just a way to make more hosts. But the consecration leads to Communion. Christ becomes present in the bread and wine as food, not only to be looked at and adored, but to be eaten. The bread is consecrated and becomes the body of Christ in order to be received by the body of Christ.

As the Mass culminates in communion, so does eucharistic adoration: "When the faithful adore Christ present in the sacrament, they should remember that this presence derives from the sacrifice and has as its purpose both sacramental and spiritual communion" (Holy Communion, n. 80). Exposition, in particular, "invites us to the spiritual union with him that culminates in sacramental communion." Nothing in exposition should "in any way obscure Christ's intention of instituting the Eucharist above all to be near us to feed, to heal, and to comfort us" (Holy Communion, n. 82).

Praying before the Blessed Sacrament, then, can focus not only on adoring the Real Presence, but can also open us up to other "dimensions of the Mystery" that happen at Mass and in communion. In eucharistic adoration, we can ponder the implications of our participation in the liturgy already celebrated and foster the appropriate attitudes to prepare for the next.

Communion meal

The first "dimension" of the Eucharist that John Paul II mentions in his letter is that of a meal. "There is no doubt that the most evident dimension of the Eucharist is that it is a meal. The Eucharist was born, on the evening of Holy Thursday, in the setting of the Passover meal. Being a meal is part of its very structure .… As such, it expresses the fellowship which God wishes to establish with us and which we ourselves must build with one another" (n. 15).

As a meal, the Eucharist establishes "fellowship," or unity — unity with God and with one another. Ultimately, this is God's plan of salvation, to unite all things in heaven and on earth in Christ (see Ephesians 1:9-10). In the Eucharist, God's plan is furthered as we are united with both Christ and the church. "This special closeness which comes about in Eucharistic ‘communion' cannot be adequately understood or fully experienced apart from ecclesial communion … The Church is the Body of Christ: we walk ‘with Christ' to the extent that we are in relationship ‘with his body'" (Mane Vobiscum n. 20).

"It is the one Eucharistic bread which makes us one body," the late pope's letter continues. "The Eucharist is both the source of ecclesial unity and its greatest manifestation. The Eucharist is an epiphany of communion." "It is a fraternal communion, cultivated by a ‘spirituality of communion' which fosters reciprocal openness, affection, understanding and forgiveness" (Mane Vobiscum n. 21).

Placing ourselves before Blessed Sacrament, we might ask Christ to "open us up to the mystery" of this communion. Where is Christ calling me to closer unity with him? How can I live in closer unity with others? What am I doing to cultivate a spirituality of communion? How can the bonds of affection, understanding and forgiveness be strengthened in our parish? How is God calling me to open myself more to the mystery of fellowship with God and others?

Sacrifice

While the Eucharist is a meal, it is also a sacrifice. "Yet it must not be forgotten that the Eucharistic meal also has a profoundly and primarily sacrificial meaning," says John Paul II. "In the Eucharist, Christ makes present to us anew the sacrifice offered once for all on Golgotha." In the Mass, Christ's paschal mystery — his suffering, death and resurrection — is recalled and made effective for those who participate.

The Eucharist, however, is not only oriented to Calvary, but to Christ's sacrifice as it is continued in the life of the church. In every Eucharist, Christ joins our present sacrifice to his, so that we might offer ourselves to God with Christ as a "holy and living sacrifice" (Eucharistic Prayer III). Describing the Mass, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy from Vatican Council II says that the faithful offer Christ with the priest, and by this "they should learn to offer themselves as well; through Christ the Mediator, they should be formed day by day into an ever more perfect unity with God and with each other, so that finally God may be all in all" (n. 48).

Prayer before the Blessed Sacrament prepares us to offer ourselves in Mass. "Offering their entire lives with Christ to the Father in the Holy Spirit, they draw from this wondrous exchange an increase of faith, hope and love. Thus they nourish the proper dispositions to celebrate the memorial of the Lord as devoutly as possible and to receive frequently the bread given to us by the Father" (Holy Communion, n. 80). In our "wondrous exchange" of prayer, we offer our entire lives with Christ, and so are prepared for celebrating the Eucharist.

Pondering the Mass as sacrifice, we open ourselves to the mystery of Christ's self-offering as the pattern for our lives. How do I imitate Christ's sacrifice? Where in my life now do I carry the cross? How might I share more deeply in the paschal mystery? What joys and accomplishments of the week will I offer to God next Sunday at Mass?

Thanksgiving

Offering ourselves is the way we offer thanks to God in the Eucharist — the meaning of the word itself is "thanksgiving." Participating in the Eucharist, John Paul II says in his letter, fosters in us a "Eucharistic attitude," an attitude "which commits us constantly to give thanks for all that we have and are" (n. 26). In fact, when we say "Amen" to the eucharistic prayer we pledge to adopt this attitude, for the prayer begins with our recognition that "we do well always and everywhere to give [God] thanks." We promise to give thanks to God not just now, as we pray the eucharistic prayer, and not just here, in church, but "always and everywhere." The great thanksgiving prayer at Mass is a sign and a promise of the gratefulness with which we live every day.

Opening ourselves to this dimension of the mystery, we might ask: How am I giving thanks to God in my present life? Do I approach life with gratitude, or I am always complaining, finding fault, seeing what's missing rather than the gifts I have been given? What is one thing I can do this week to extend the prayer of thanks within my life? How can I show gratitude to others?

Advertisement

Service

Our grateful self-offering in Mass leads to service, love and acts of charity outside of Mass. The ritual for the worship of the Eucharist assumes that those who pray before the Blessed Sacrament not only "pour out their hearts before him for themselves and for those dear to them" but also "pray for the peace and salvation of the world" (Holy Communion 80). In addition to intercessory prayer, the Eucharist "moves them to maintain by the way they live what they have received through faith and the sacrament. … All should be eager to do good works and to please God, so that they may seek to imbue the world with the Christian spirit" (Holy Communion 81).

Doing good deeds preserves what we received in Mass — not just charitable acts in our immediate circle, but also working for change in society. "The dismissal at the end of each Mass is a charge given to Christians, inviting them to work for the spread of the Gospel and the imbuing of society with Christian values" (Mane Vobiscum n. 24).

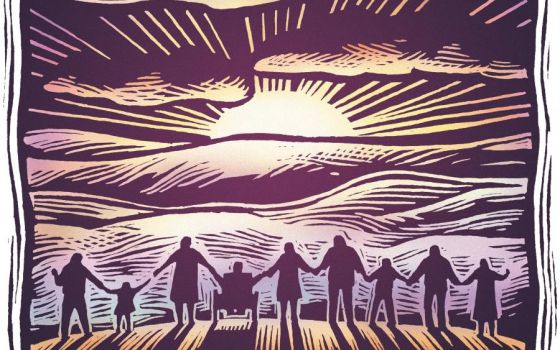

Reminding us that "the Eucharist is not merely an expression of communion in the Church's life; it is also a project of solidarity for all of humanity," John Paul II's letter points specifically to the mission of peace that flows from the Eucharist. "The Christian who takes part in the Eucharist learns to become a promoter of communion, peace and solidarity in every situation. … More than ever, our troubled world, which began the new Millennium with the specter of terrorism and the tragedy of war, demands that Christians learn to experience the Eucharist as a great school of peace, forming men and women who, at various levels of responsibility in social, cultural and political life, can become promoters of dialogue and communion" (Mane Vobiscum n. 27).

Celebrating Mass and eucharistic adoration should result in "a practical commitment to building a more just and fraternal society" (Mane Vobiscum n. 28). In a climate where many Catholics express concern about the "correct" or proper celebration of the Eucharist, Pope John Paul II asserts that the chief way to judge the authenticity of the liturgy is by our service of the least. At the end of his letter, he pleads:

"Can we not make this Year of the Eucharist an occasion for diocesan and parish communities to commit themselves in a particular way to responding with fraternal solicitude to one of the many forms of poverty present in our world? I think for example of the tragedy of hunger which plagues hundreds of millions of human beings, the diseases which afflict developing countries, the loneliness of the elderly, the hardships faced by the unemployed, the struggles of immigrants … We cannot delude ourselves: by our mutual love and, in particular, by our concern for those in need we will be recognized as true followers of Christ (cf. John 13:35; Matt 25:31-46). This will be the criterion by which the authenticity of our Eucharistic celebrations is judged" (n. 28).

Adoration of Christ in the Eucharist can never remain simply a personal prayer. Like the celebration of the Eucharist, it calls us to work for peace and to give concrete service to the needy. What would it mean for me and for my parish to see the Eucharist as "a great school of peace"? How can we act on behalf of the least? as a parish? as a family? Am I serving Christ where he said he would be found: in the hungry, the sick, the imprisoned?

Eucharistic attitudes

The Eucharist could only have an effect on the world, Pope John Paul II instructed in his letter, if each member of the faithful would "assimilate, through personal and communal meditation, the values which the Eucharist expresses, the attitudes it inspires, the resolutions to which it gives rise" (n.25). This is precisely the opportunity given in eucharistic adoration, as we open ourselves up to the mystery in all its dimensions.

Editor's note: This reflection was originally published in the August 2005 issue of Celebration.