Crosses installed during a protest against Russia's actions in eastern Ukraine are pictured Feb. 23 in front of the Russian Embassy in Kyiv, Ukraine. The signs on the crosses read: "Russian occupier." (CNS/Reuters/Valentyn Ogirenko)

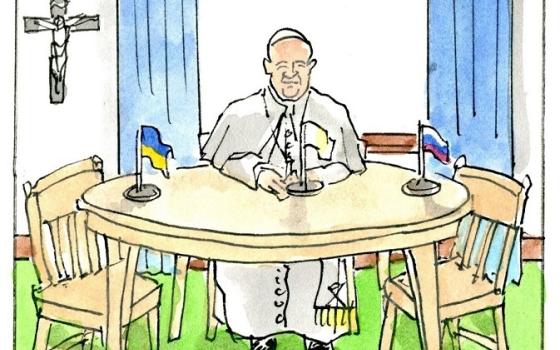

For weeks now, in Sunday Angelus addresses and in his general audiences on Wednesdays, Pope Francis has been pleading against war and calling for peace in Ukraine, dedicating an entire day for prayer and fasting for the country on Jan. 26 and calling for another one at the start of Lent on March 2, Ash Wednesday.

Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican's secretary of state, has also communicated directly with the leadership of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, offering his assurances of solidarity with the church and the country.

In all of these appeals from the Holy See, however, one word has been missing: Russia.

"People are afraid to say that Russia is an aggressor," said Daniel Galadza, "because it's either politically inconvenient or because Russia has extreme financial resources."

Galadza, who is a deacon of the Kyiv Archeparchy of the Ukrainian Catholic Church and a liturgy professor at the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome, told NCR he would like the Holy See not to be shy to speak about the specifics of Russia's attempts to invade the country.

Pope Francis greets people near a banner in Italian calling for the pope's intervention between Russia, Ukraine and NATO, during his general audience in the Paul VI hall Jan 19 at the Vatican. (CNS/Vatican Media)

While the Holy See desperately wants peace in Ukraine, it is also eagerly seeking to continue its détente with the Russian Orthodox Church, from which it has been split since the Great Schism of 1054.

Pope Francis and Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill of Moscow made history in Cuba in 2016 as the leaders of the Catholic and the Russian Orthodox Church met for the first time ever and declared "we are brothers."

At the same time as diplomats, including those of the Holy See, are working to prevent a full-on Russian war against Ukraine, which world leaders have warned could be the biggest war in Europe since 1945, the Holy See is also trying to broker a second meeting between the pope and the patriarch.

Earlier this month, in the midst of the current crisis, Russian Ambassador to Vatican City Alexander Avdeyev said the meeting could happen this summer.

In Rome, the rooftop of the Pontifical Ukrainian College of St. Josaphat directly overlooks the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Catherine of Alexandria and the residence of the Russian Federation's ambassador in Rome — which is exactly the direction some Ukrainian Catholics believe the Holy See should set its sights as Russia begins an invasion in Ukraine.

The Russian Orthodox Church of St. Catherine of Alexandria and St. Peter's Basilica are seen in Rome May 20, 2010. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Metropolitan-Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, who spent three weeks in Ukraine at the beginning of February before coming to Rome for a conference, told NCR that he understand there may be limits to how forcefully Vatican officials can speak publicly about the situation.

"We don't always like to point the finger directly at sinners," he said, but added that he would like the Holy See to "encourage the Russian Orthodox Church to be at least somewhat prophetic" in the current situation.

During his two decades as leader of Russia, President Vladimir Putin has used the Russian Orthodox Church to amass power, and in return, the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church has offered him its backing.

Gudziak said that the church has helped Putin's regime in its empire building aspirations.

"The Russian Orthodox Church is formulating colonial policy for Russian society," he said, adding that Russia's latest attempts to control Ukraine is evidence of this and he would like the Holy See to challenge Russian Orthodox leaders on this front.

Metropolitan-Archbishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Archeparchy of Philadelphia speaks at a meeting hosted by the Vatican Congregation for Eastern Churches Feb. 16 in Rome. Representatives of Eastern Catholic churches attended the conference marking the 25th anniversary of a Vatican document encouraging Eastern Catholic churches to preserve and promote an understanding of their liturgical traditions. (CNS/Paul Haring)

"Pope Francis has said many times that whenever Christians get caught up in power and money, we betray our vocations," Gudziak said. "When we are behind invasion and war, it's scandalous."

The Holy See, he continued, needs to be clear about what is at stake: questions of human dignity and freedom and political, cultural and spiritual self-determination.

"It's really important that the Holy See, and all Catholics and all people of goodwill, stand up for what is true," Gudziak told NCR, adding that he directly discussed the situation in Ukraine in an audience with Pope Francis on Feb. 18.

Despite the looming prospects for full-on war, Gudziak describes Ukranians as "resilient" and with a "firm resolve" to protect their homeland.

After spending several weeks at the Ukrainian Catholic University, where he was once the rector and president, and spending time with Ukrainian Catholic bishops, Gudziak said there is both a sense of a "mounting apprehension" and a "stoicism" that is evident among the country's citizens.

"People know what war is," he added. "Their stoicism is not denial."

For that reason, he said, young women are taking courses in first aid, people have prepared their suitcases in case they need to seek refugee status elsewhere and a number of people are joining local territorial defense units and undergoing training, ready to fight and defend their country.

Advertisement

Basilian Fr. Robert Lisseiko, who serves as spiritual director at the Pontifical Ukrainian College of St. Josaphat, said that among the 53 Ukrainian seminarians currently living there in Rome, there is a sense of worry and distraction as friends and family members at home have signed up to serve in the military.

"There is the hope that the world will do something more, especially the European countries," he told NCR, but added that "hope is lacking" given the continued escalation by Russia.

Former vice-rector of the seminary, Basilian Fr. Teodosiy Hren offered a similar assessment, saying there is a fear — not of Russia, but "because every war brings destruction, death, disability, pain."

"Our people are not afraid in front of a Russian monster, in front of its weapons and military power," he said.

A Ukrainian frontier guard patrols an area along the Ukrainian-Russian border Feb. 23 in the Kharkiv, Ukraine. Pope Francis expressed "great sorrow" over the situation in Ukraine and called on Christians to observe a day of prayer and fasting for peace on Ash Wednesday, March 2. (CNS/Reuters/Antonio Bronic)

As a ground war has now commenced, Lisseiko said a war against truth had already preceded it through Russian propaganda in the media.

He said he was dismayed by this, in a country led by someone who has flaunted his Christian values and who has actively used the Russian Orthodox Church to push his agenda.

"Where have Christians gone that they are afraid to tell the truth to the government that they are doing something really diabolical?" he asked.

It's for this reason that Galadza would like for the Holy See to get specific when it talks about the situation in Ukraine and to directly mention Russia.

In the same way the Catholic Church has learned to talk not simply about "Africa" or "the Middle East" but to speak directly about the realities in specific countries, the same is needed for Eastern Europe, he said.

"What Ukraine needs is for the ability to speak the truth in love and not to be afraid to tell brothers and sisters in Christ that they also need to speak the truth in love," he said. "They should not talk in general terms about peace and Eastern Europe because that's the equivalent to saying thoughts and prayers."

"Thoughts and prayers are extremely important," he added, "but the Holy See has a huge influence in all of Eastern Christianity and it can do something."