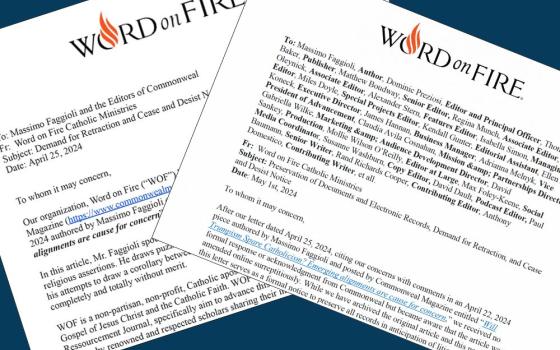

Migrants from a nearby encampment can take free clothes at the parish meeting hall of St. Thomas Aquinas Church in Brooklyn. (Courtesy of St. Thomas Aquinas Church)

On a sun-drenched spring morning, Nicolas walks with his friend Jimmy across the over 1,300 acres of Floyd Bennett Field, perched on the far edges of Brooklyn, steps from the sea. It's been his home for two months after he arrived in New York. On his way to the bus, he checks out the items at a pop-up giveaway stand.

A hot item are suitcases, gobbled up quickly by migrants who find themselves regularly on the move. The children go after the few soccer balls. As for clothing, Nicolas finds nothing that can fit his burly build, yet continues unperturbed. He likes to talk but knows hardly any English.

In the complicated world of U.S. immigration policy, Nicolas is eligible for a work permit, being from Venezuela. His friend Jimmy, from Peru, is not. They go together to the parking lot at a nearby Home Depot, where they wait for daywork in gardening or home renovations. The last names of Nicolas and Jimmy are withheld here because of their uncertain immigration status.

The presence of Nicolas is a slice of a continuing national debate. Immigration is among the top issues on voters' minds this presidential election year, along with inflation and the overall economy. In the middle of this political drama is St. Thomas Aquinas Church, a Catholic parish just ten miles away from Floyd Bennett Field, trying to live out its mission of social justice by helping the thousands housed at the encampment. According to the pastor, Fr. Dwayne Davis, "It's not about politics for us. It's about living the Gospel."

But living the Gospel can be daunting. Nicolas shares his tent accommodations at the field with about 2,000 other migrants. The tents were hastily constructed last year to shelter just some of the more than 180,000 migrants who have arrived in New York City over the past two years. That is more than the population of Syracuse, the state's fifth-largest city.

Fr. Dwayne Davis, pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas in Brooklyn, spoke to NCR about the parish's work to help migrants at a nearby encampment: "It's not about politics for us. It's about living the Gospel." (Courtesy of St. Thomas Aquinas Church)

The migrant crisis infuses nearly every other issue in New York City, including housing and crime. It occupies much of the focus of New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a former police officer who was elected on promises to address crime and disorder while maintaining progressive values.

New York is officially a sanctuary city with a policy which promises shelter to anyone who needs it. But that promise is increasingly hard to keep with a growing migrant population and a native population seeking housing amid rising rents. The city recently imposed limits on shelter, directly impacting adult migrants. Near the encampment here, reports of migrants knocking on doors and begging for food and clothing have frightened some residents.

"While #NYC residents are pushed out by costs, the city uses your tax money to build more tents for migrants. We can't afford this! We can't sustain this. Why are our elected officials doing NOTHING ?!" tweeted firebrand Curtis Sliwa on April 17. Sliwa, a radio talk show host, former Republican candidate for mayor, and founder of the Guardian Angels anti-crime unit, is a leader of the opposition to the encampment here.

Sliwa has been a main speaker at "Topple the Tent" rallies held this winter outside Floyd Bennett, attracting hundreds of local opponents. He has labeled Adams as the "mayor of the illegal aliens" and raised the specter of terrorists and sex traffickers among the migrants.

But Nicolas and his fellow migrants have found a better welcome from some local Catholics, including those at St. Thomas Aquinas, a parish founded in 1885 to serve earlier generations of immigrants. Fr. Davis recalled that the Floyd Bennett Field camp was established before anyone in the parish knew about the plans. Last winter, scores of migrants, many from more tropical climates who had traveled thousands of miles through Central America on foot, suddenly knocked on the church door seeking help.

"We didn't have anything in place, but we knew we had to do something," Davis told NCR. "It was a cold time. Migrants were coming here in shorts and T-shirts," he said.

Fr. Dwayne Davis established the Matthew 25 Ministry at St. Thomas Aquinas to provide clothing and other needs to migrants. Once a week migrants take the city bus to the church, seeking out needed items. (Courtesy of St. Thomas Aquinas Church)

Davis established the Matthew 25 Ministry at the parish, providing clothing and other needs to the migrants, following Jesus' biblical injunction to do likewise. Once a week migrants take the city bus to his church seeking out needed items. In the winter months, they numbered in the hundreds. As the harsh weather subsided, they now number a few dozen.

Davis is himself an immigrant, having come to Queens at the age of 12 with his family from Jamaica. He is sympathetic to the migrants' plight but recognizes their presence here is wrapped up in the ongoing immigration political wars. Parishioners are divided. But, said Davis, "We had to do the Christian response." While the migrants' presence created division, he noted, "They are already here."

Raquel Florez, a recent graduate of Brooklyn College, coordinates the parish response along with about a dozen other volunteers, all women. They work with little publicity about what they do, and they keep the once-a-week clothing drive times known only to the migrants themselves.

"It's kept very quiet," she said. "There are people in our neighborhood who don't agree. They put politics first in place of supporting people in need." One neighbor's house, she noted, sports a prominent sign, telling those ringing doorbells seeking food to stay away.

The outreach to migrants at St. Thomas Aquinas goes beyond basic support. It includes presentations from Catholic Charities attorneys and immigration workers, who offer counseling and legal help for migrants seeking asylum.

Small group of locals are helping the migrants in other ways. The pop-up clothing stand is organized by three women with connections to Rockaway, a short walk across the Marine Parkway-Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge from Floyd Bennett. Their project doesn't have a name. The trio gather what they can from Rockaway residents and show up outside the gates of Floyd Bennett Field, near the bus stop, with loads of clothing and other goods that are quickly disposed of.

Sometimes the needs are jarring.

Clothing distribution takes place in the parish meeting hall of St. Thomas Aquinas Church. The hall is actually the original church, which was built in the late 1800s. (Courtesy of St. Thomas Aquinas Church)

One of the group noticed a Venezuelan young woman, just arrived to a New York winter, clad only in shorts and a T-shirt. The volunteer brought her to her car, took off her own pants, and gave the clothing to the migrant, providing some resistance to the winter chill. Laura Glabman, one of the three volunteers, enlisted the support of the National Council of Jewish Women, as well as contacts in Long Island thrift shops, to regularly fill two mini-SUVs with material that is quickly dispersed over the course of two hours.

Those who show up at the impromptu clothing site are frequently from Latin American countries, particularly Venezuela, with others from Peru, Ecuador, and Honduras. Others are from Haiti as well as China. The junior-high aged son of a Turkish woman translates for his mother, who says the family is escaping persecution because they have suffered as Christians in a Muslim country. They arrived via airplane to Mexico and went through the border crossing near San Diego before coming to New York. Her husband will soon join them, she said.

Daero, from Venezuela, is on his way to a Manhattan immigration hearing on his case scheduled that afternoon. Darwin, from Ecuador, has been here for four months, after walking with his wife and three children through Central America before arriving in Texas.

Advertisement

While some in the neighborhood provide as much support to the migrants as they can, the opposition to the migrants' presence is louder, more organized. It's also reflective of the majority of local residents, says Joann Ariola, the city council member who represents Rockaway and adjoining Queens communities. In packed community meetings, she has emphasized that while she is sympathetic to the plight of the migrants, Floyd Bennett Field is not a good spot for them.

"It's not a proper place to house anyone," Ariola said.

She argues that its isolation puts the migrants far away from schools and stores. The field tends to flood and, in one downpour during the winter, migrants were forced to move for a night from their tents to seek shelter in a Brooklyn public high school as water threatened their temporary dwellings. The move was framed as a national story by Fox News as an indication that education for young citizens was being sacrificed for migrants.

And, as summer nears, other issues have emerged among nearby residents.

"People are fearful of using that park," said Ariola, noting that the migrants' presence is discouraging locals from fishing off Jamaica Bay, paddle boating, and using nearby soccer fields adjoining the field. She hears regularly from constituents in Rockaway, its beaches a magnet during the summer months, who say they are concerned that migrants will engage in illegal vending on the boardwalk — a favorite product being flavored ice — beg and perhaps steal from residents and visitors.

The migrants will be here at least through September, when the lease between the city and the National Parks Service will have run its course.

What then? Ariola, one of six Republicans on the 51-member New York City Council, suggested that the migrants be moved to the Park Slope Armory, in affluent brownstone liberal Brooklyn, whose representatives have expressed support for the migrants. For its part, the Adams administration has been quiet on what the future might hold as the mayor lobbies for a more comprehensive federal role to address the migrant crisis.

Meanwhile, the migrants at Floyd Bennett shop at the pop-up clothing store, seeking out what's needed for their children, including shoes and coloring books. Also on the list are maletas, suitcases. Even if they don't realize the extent of the furor around their presence, they know for sure they will be on the move once again.