Sr. Lisa Buscher, of the Society of the Sacred Heart, shares candy with children at a migrant shelter in Mexicali, Mexico, on May 9. Buscher, who works with migrants and refugees in San Diego and border communities nearby, urges a compassionate view of migrants. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Editor's note: Global Sisters Report launches a new series, "Welcoming the Stranger," which takes a closer look at women religious working with immigrants and migrants. The series will feature sisters and organizations networking to better serve those crossing borders, global migration trends and the topic of immigration in the upcoming U.S. presidential election.

As immigration becomes a hot-button topic in the upcoming U.S. presidential election, women religious and other Catholics urge a compassionate Christian response toward people fleeing perilous situations in record-breaking numbers.

"If we changed what was being preached at our pulpits and talked about a God who migrates toward us, we'd have a different understanding of what people on the move, migrants, are about," said Sr. Lisa Buscher, of the Society of the Sacred Heart, in a Jan. 8 interview with Global Sisters Report.

In December, authorities documented more than 225,000 migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border, a record for monthly encounters. It was not a surprise since the government had released figures two months earlier of more than 2.4 million apprehensions at the southern border in the 2023 fiscal year, which ended in September. It was the third record-setting year in a row, The New York Times reported.

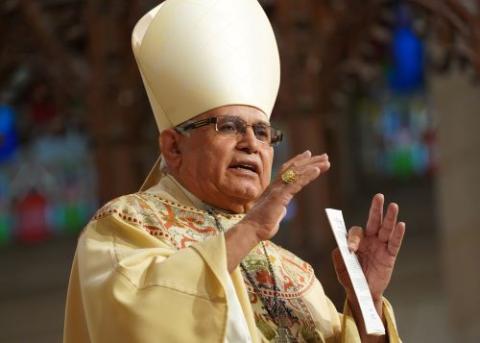

'The mandate of our Lord Jesus Christ is very clear: I was a foreigner and you welcomed me.'

—Cardinal Alvaro Ramazzini

Some Republican state leaders have transported migrants from border cities to localities run by Democrats, spurring politicians on both sides of the aisle urging the federal government to do something to stop the flow. Some have publicly voiced their frustrations, and Republican and Democrats in the Senate are working together on an agreement: Their deal would grant the Biden's administration request for money for Ukraine if it agrees to limit a temporary status called humanitarian parole, which has allowed a large number of migrants — including from Ukraine and Nicaragua — to stay in the United States.

But it's not the only bipartisan show of discontent when it comes to immigration.

Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began sending busloads of migrants to New York City in spring 2022. In September, Mayor Eric Adams, a Democrat, said he didn't see a way to fix the problems associated with such rapid-pace migration — emergency food and shelter and ballooning school enrollment — and said it would "destroy New York City." Former President Donald Trump said in a December rally that migrants are "poisoning the blood of our country."

It was a sentiment 82% of Republican registered voters shared, a January CBS News poll showed.

An aid worker greets migrants arriving from Texas by bus at the Port Authority bus terminal in New York City May 10. (OSV News/Reuters/Andrew Kelly)

For women religious like Buscher, who works with migrants and refugees in the San Diego area, it's hard to understand the sentiments.

Buscher urged people to look more critically at global migration. Conflicts such as Russia's war against Ukraine; conflicts in places such continental Africa; economic and political conditions in Latin America; and climate change and hunger, she said, have spurred a global flow of people, with the U.S. one of many destinations for migrants.

"These are ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. It could be any one of us," she said.

In the Catholic tradition, she said, the Holy Family had to deal with similar challenges as Joseph and Mary fled their homeland to protect the baby Jesus from being killed by King Herod.

"It's all in our biblical stories, it's all part of the flight from Egypt," Buscher told GSR. "People were on the move then. We forget that part of our story."

Sr. Maria de los Dolores Palencia Gómez, of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Lyon, who works with migrants in Mexico, stops to chat with two sisters in Bogotá, Colombia, on Nov. 24. Palencia said Christian teaching toward migrants can be found in the Gospel of Matthew, "which clearly tells us: you clothed me, I was a foreigner and you welcomed me." (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Sr. Maria de los Dolores Palencia Gómez, of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Lyon, who works with migrants in Mexico, said it's hard to know what she'd say to U.S. politicians who boast about their Christianity yet "use" anti-immigrant sentiment to attract voters.

"I don't think it's possible, as Catholics, to feel exempt from reaching out to a brother or sister. It's enough to look at [the Gospel of] Matthew, which clearly tells us: you clothed me, I was a foreigner and you welcomed me," Palencia told GSR during a press conference in Bogotá, Colombia Nov. 24.

Yet using migrants and immigration for political gain or to divide a community isn't limited to the United States, Palencia added. In Mexico, a country also electing a president in 2024, "politicians use hot topics" related to immigration for "propaganda," Palencia said.

Sr. Maria Elena de San Jose, of the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration of the Most Sacred Sacrament, waits in line to cross into the United States at the Bridge of the Americas Port of Entry from Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, toward El Paso, Texas, May 13. She said her contemplative order prays so that governments can better help migrants. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Some politicians may even say they vote against something like abortion rights, for example, because of their pro-life Christian view of the world, yet oppose immigration — which Palencia says is "incoherent" with Christian beliefs.

"Each time we talk about pro-life, it ends up in a discussion about abortion, but I say if you're pro-life, you have to defend all life, starting with the life of Mother Earth, the life of a human being at any stage, and the defense of people who are dying of hunger, because being pro-life is about defending the life of those who have no rights," Palencia said. In many cases, that involves the life of migrants, she said.

Cardinal Alvaro Ramazzini, bishop of Huehuetenango, Guatemala, said a Christian's commitment to care for life includes immigration, and it means caring about the conditions that support a life of dignity in other countries. He and El Paso Bishop Mark Seitz spoke with GSR about immigration Nov. 9 in Washington.

Cardinal Álvaro Ramazzini of Huehuetenango, Guatemala, delivers his homily as he celebrates a special Mass in honor of the Black Christ of Esquipulas, Guatemala, on Jan. 5, 2020, at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City. (OSV News/Gregory A. Shemitz)

In Guatemala, young men and women dream of leaving in search of jobs that don't exist in their rural towns, Ramazzini said. Government corruption, violence, lack of attention to economic development in poor areas, and climate change, have led many to risk their lives for dreams that aren't always fulfilled by migrating, he said.

"There's an attraction of coming here [to the U.S.] thinking that they'll have a better future because that's the promise of the coyotes [smugglers]," he said. "But often [migrants] arrive in the U.S. and find themselves without jobs, being thrown out or threatened in places like Florida because they don't have [legal documents]. It's a big problem and we have to make them aware that the dreams of the U.S. can become a nightmare. It's not what they're expecting."

People in the U.S. concerned with increasing migration should also be concerned with improving conditions in sending countries, finding ways to strengthen democracy, human rights, security and peace elsewhere, Seitz said. He chairs the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' migration committee and has worked with faith-based groups seeking ways to alleviate root causes of migration.

Though much is said about migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, countries where the migrants come from also suffer "a great loss of human beings with values with dreams" who sometimes fall for the "illusion" of arriving in a country that isn't always welcoming, Ramazzini said.

Advertisement

It puzzles him, he said, when he comes to the U.S., where people are proud to talk about Christian identity.

"The mandate of our Lord Jesus Christ is very clear: I was a foreigner and you welcomed me. It gives me a lot to think about in the U.S. where many profess Christianity, but I don't see a practice of that faith when I encounter a sentiment of xenophobia, a sentiment against migrants," he told GSR. "Migrants aren't thieves. They don't come here to steal. They come to work."

He said he's aware of the strong culture of the separation of church and state in the U.s. Even so, helping a person in need "is not a religious matter," he said, "it's a matter of humanity."

That's why Ramazzini tells Guatemalans thinking of going to the U.S. that migrating means suffering, "from the cold in winter, the heat in summer, coming into contact with people with whom they don't speak the same language."

"I tell them they're going to find a different future, and yes, you may earn many dollars," he said. "But they won't tell you what kind of work you'll be doing, the difficulties of crossing the border, they don't talk about any of the negative aspects, the separation of families, erosion of the faith because of the demands of work … in other words, the ugly side of immigration."