A year ago, Miledi Berdu and her husband, Robert Rodriguez, began skipping meals to keep their children fed as Venezuela's economic crisis continued. Rodriguez's salary as a welder in Caracas wasn't enough to cover soaring prices, and shortages made food expensive.

One day, she would skip lunch, then the next day, he'd go without dinner. The goal was to keep their 10-year-old daughter and 2-year-old son from going hungry. Berdu, already slim, dropped 11 pounds.

"The kids always had food. We couldn't tell them there wasn't food, so we tried to make sure they didn't realize," she said. "How would you explain to your baby that there's no bottle or to your child that it's all we have to eat?"

Cases like these are becoming too common to Sr. Teresa Gomez and Sr. Yexci Moreno of the Congregation of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Castres. To better understand the scope of the problem and hopefully push humanitarian and official organizations into action, the sisters have teamed up with Caritas de Venezuela, the local chapter of Caritas Internationalis, to run nutrition clinics for children under the age of 5.

On Saturdays, their preschool in the low-income area of Propatria becomes a hive of activity as volunteers and doctors weigh, measure and examine local children at no cost. Termed Survey System for Monitoring, Alerting, and Attending to Health and Nutrition (abbreviated SAMAN in Spanish), the clinics aim to simultaneously collect and monitor statistics and help children deemed malnourished.

Berdu and Rodriguez were aware that despite their best efforts, their children's diet still fell far short of qualifying as balanced. They brought their 2-year-old, Elias, to the SAMAN clinic in September, when they learned that the changes in portion sizes and types of food and the inability to find formula and vitamins had damaged Elias' health — he was severely malnourished.

"I could tell when he would stand beside other kids his age, he was too skinny," Berdu said. "And he started getting sick pretty often."

In addition to gathering information, the SAMAN program also follows up with children they determine malnourished, checking for parasites and providing them with a supplement of vitamins and nutrients to be taken twice daily. The daily supplement helped Elias reach a normal weight and size, and he's now healthy.

Rising inflation and a sinking economy

Over the past few years, Gomez and Moreno have witnessed firsthand as their community and the children who attend their school suffer the effects of Venezuela's faltering economy.

Their school serves 110 children in the local community from ages 3 to 6, providing children with both breakfast and lunch.

Moreno has noticed increasing numbers of the children who arrive at the school after summer vacation are underweight, skinny and often sick. After weighing and measuring on the first day of school, the numbers often confirm their worries.

"We are seeing serious malnutrition, and I can say that with certainty," Moreno said. "And this is something we have not seen in previous years. It's something new."

While the sisters help lead the weekly SAMAN clinics in their preschool, another worry remains present for them: the state of their school. After 30 years of operation, Moreno and Garcia now doubt whether the preschool will meet government code to open another year, mainly because of constant leaks.

"Formerly, there were a lot of donations from the families, from outside groups," Moreno said. "And those people continue trying to help, but the money they have now barely covers their own family costs."

The economic problems for the sisters at the preschool come as the result of an economy in freefall.

Reuters reported that in 2016, Venezuela's inflation reached 800 percent and the economy shrank by 18.6 percent.

The country, which relies on oil for 96 percent of its export income, has long lived through boom-and-bust cycles according to the price of oil. But many consider the current economic downturn, now in its fourth year, to be the worst the country has seen.

Without currency for crucial imports and with price controls in place, shortages of basic foods, medicines and other household products have become commonplace at traditional stores.

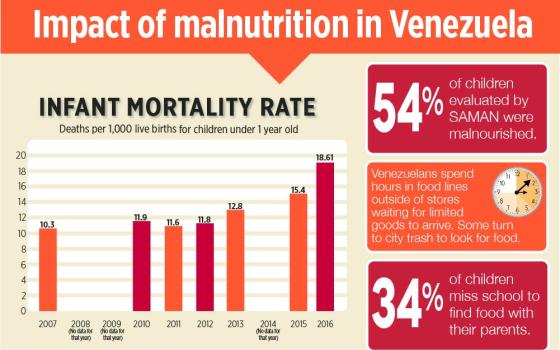

Many poor and middle-class Venezuelans spend hours, sometimes full days, in lines outside of pharmacies and supermarkets, waiting for the limited goods to arrive. Some have even have started to turn to the city's trash to look for food.

The company that used to donate lunches to Moreno and Garcia's school has canceled those donations. As a result, the sisters now face the daily challenge of finding the school's food at affordable prices, often meaning they hit the streets with other Venezuelans at 3 a.m. to wait in lines at local supermarkets.

And like all Venezuelans, they face never-ending inflation as the sisters attempt to find the materials needed to make crucial repairs.

In one recent case, Moreno found roofing materials that would have helped fix some of the school's leaks. The materials cost 54,000 Venezuelan bolívars (U.S. $78), but Moreno had yet to gather the money needed. When she did finally gather the cash, the price had jumped to154,000 bolívars (U.S. $223).

"If the school shuts down, it would mean that those kids, the food that they need and they get here in those first few years — that's the most important thing they need, because if not, they'll never recover," Moreno said.

At the preschool, Moreno and Gomez tend to their community and the children who attend their school as best they can.

"I've seen plenty of mothers who come here to the school with tears in their eyes because they don't have any food to give to their children," Gomez said. "Others will ask for just a piece of bread. That's the situation we're living."

Last year, they started offering classes to parents with tips on how to prepare cheaper meals using ingredients that remain readily available but are traditionally not popular in Venezuela. They also organize weekly soup kitchens.

"We even have people who are eating plantain peels, which is great, as we cover in the class," Moreno said. "OK, it could even be delicious, but in past years, nobody would have even thought about eating that."

Plantains and bananas are staples of the Venezuela diet, but the peels are rich in vitamins B-6 and B-12, magnesium and potassium, too. Instead of tossing the peels in the trash, Moreno and Gomez encourage those participating in the alternative cooking classes to boil them and eat them as a side dish.

The weekly soup kitchens serve hundreds in the community on Saturdays, and many of them also attend the SAMAN clinics. The sisters use whatever ingredients they've managed to accumulate during the week to make vats of soup and rice, although they worry that one weekly meal does little to alleviate hunger.

"In some ways, we even worry that we're wasting that food," Moreno said. "What can one weekly meal do to really help people? They need more."

The edge of a humanitarian crisis

In collaboration with volunteers from Caritas, the sisters also help run the SAMAN clinics as a study of sorts, carefully noting each child's measurements, which will be combined into periodic bulletins.

Although they also measure and weigh anyone who asks, the program targets children under 5, a crucial age when any nutritional deficiencies could cause death or lifelong intellectual disorders.

"The scientific community in nutrition is certain that whatever your potential in life will be, physically and mentally, it will be determined by the quality of your first 1,000 days of life," said Dr. Susana Rafalli, SAMAN's leading nutritionist.

Doctors determine each child's nutritional health using World Health Organization standards for measurements of a child's arms and height, along with their weight, and a medical exam checking for any conditions that could signal a nutritional deficiency.

Since its launch in September, the program has evaluated over 900 children in several neighborhoods of the capital, along with four other states, from the most Western state of Zulia to the coastal state of Vargas.

In the absence of current official figures, last published by the National Institution of Nutrition in 2007, Rafalli said the results provide a snapshot of the state of nutrition for Venezuelan children in high-risk areas, although she said the findings cannot be generalized to the whole population. She calls the findings alarming.

In its first official bulletin in late January, SAMAN released figures showing 54 percent of children evaluated are malnourished. Nine percent of children suffered from severe acute malnutrition.

Those numbers represent a major jump from UNICEF and WHO figures from the country in 2011 that showed 3 percent of children suffered from severe acute malnutrition.

"In terms of malnutrition, I would say that the scale and the intensity of the nutritional problem is three times of the problem that we were expecting," Rafalli said.

Frameworks from international bodies such as WHO and from the Integrated Food Phase Classification system classify figures showing any area where 10 percent or more of children face severe acute malnutrition as on the cusp of a humanitarian crisis. Should those numbers reach 15 percent, the situation classifies as an emergency.

While the numbers released during the first three months of study by SAMAN reveal 9 percent of children facing severe acute malnutrition, Rafalli estimates that this year, the number could reach 12 percent.

Broken down regionally, the survey presented other alarming findings: In Vargas state, the figures of children with severe acute malnutrition exceed 10 percent, while in Zulia, the number is closer to the emergency levels of 15 percent. Sixty percent of children in Zulia also showed signs of anemia.

While the surveys don't offer information regarding the precise causes of the levels of malnutrition, Rafalli points to three areas that affect a child's well-being, all of which she believes to be faltering given the economic crisis: health, food and care.

In the area of health, Venezuelans face shortages of 55 to 60 percent of basic goods at affordable prices. When parents do successfully acquire those goods, it generally comes after spending several hours waiting in line, negatively affecting the care of their children. When children need a checkup, they face more difficulties from a struggling public health system and medicine shortages, Rafalli said.

"If we consider all of these factors together, including health care, we could face, in short, a situation of catastrophic dimensions," Rafalli said.

That's why she has teamed up with the church and its Caritas program and with sisters like Garcia and Moreno across the country to better track and address the situation. She said the church is a key humanitarian actor — partly because of the trust it enjoys among the population — that can positively influence other nongovernmental organizations and governments to help.

The weekly nutrition clinics at the preschool and in other centers, most of them Catholic schools and churches, will continue.

For mothers like Iyudelsi Avila and her 18-month-old daughter, Rebecca, the program couldn't have come sooner.

Because Avila was unable to get her hands on formula and because her poor diet affected her breastmilk, Rebecca arrived at the SAMAN clinic weighing a little over 15 pounds, a weight she had maintained for several months.

But in the month since receiving the nutrients from SAMAN, Rebecca has gained 4 pounds.

"Now she has an appetite that you couldn't imagine, and she sleeps sometimes until 10 a.m.," Avila said.

[Cody Weddle is a freelance journalist based in Caracas, Venezuela. Follow him on Twitter: @coweddle.]