Jesus the Migrant! I never thought of Jesus as a migrant until I read the book review of Deirdre Cornell’s book by that title at the National Catholic Reporter site. But of course, he was. He was always crossing borders whether physical, spiritual or religious. His migrant life started as a baby traveling to Egypt to escape from Herod. It is sad that these same conditions remain today, people fleeing death and destruction, war and discrimination. But, borders are getting harder and harder to cross.

Just last January the Archbishop of Angola was invited to attend the Confederation of Major Superiors of Africa and Madagascar (COMSAM) in Kinshasa. He arrived at the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo late one night, but, without a visa, thinking because he was a Catholic bishop he would be allowed in. However, the DRC shows favor to no one. To his astonishment, he was sent back to Angola.

Unlike the archbishop, I knew I needed a visa, but discovered it was not easy to get. It took seven weeks of panic and many emails to convince the program committee that I needed a letter of invitation notarized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kinshasa. Miracles do happen at Christmas. On December 30 the correct letter arrived, and the document agency in Washington, D.C., was able to have the visa authorized at the DRC embassy the morning of the 31st.It arrived on my Los Angeles doorstep January 2 in time for my departure. Crossing borders is not without stress.

But from 1961 to 1975 crossing was still easy. Angolans crossed many borders fleeing from a war of independence and the civil war that followed. According to the U.N. refugee agency, 550,000 people crossed borders into the DRC, Zambia and Namibia during that period. I remember visiting Angola in 2006, learning that people were still afraid to return because of undiscovered land mines. I saw bombed-out sections of Luanda, the capital, and thousands of people living in sandy slums without easy access to water, sanitation or garbage disposal. Children rummaged through mountains of refuse for food. Another shock was the contrast of the other Luanda being built by diamond and oil businesses.

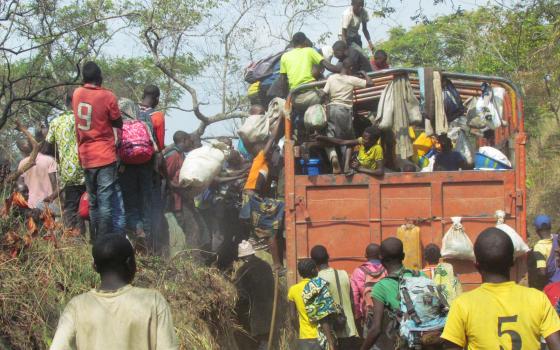

As I drove through this “other city,” it was hard to imagine the sandy slum city existed. Gradually refugees returned from the neighboring countries, but at the end of 2012 more that 78,000 refugees still made their home in the DRC. These migrants and refugees had lived for years in United Nations-sponsored camps, where it was a challenge to survive.

Finally, in 2012 DRC authorities said it was safe to return home. Families planning to apply for immigration permits had to find other living situations. Making the Congo home while they waited in hope of acceptance without resources and few skills is unnerving, and many are still waiting. The bishop of Kisantu diocese is host to many of the waiting Angolan families. Needing help, he invited Scalabrinian Missionaries to develop programs for the women and children at the borders between Angola and the DRC.

Two Brazilian Scalabrinian Missionaries, Srs. Marizete Barbin and Luciana Pitol, began work in 2012. They know from past experience in South Africa and Mozambique that work with migrants is challenging. Trauma from rape is very common among the women, and because of poor nutrition and lack of health care, so is fistula. The sisters transport women from the borders to Kinshasa to have fistulas repaired by doctors from Belgium.

They also supervise food distribution and to families during the rainy season, when access is limited.

Getting children into school required opening one near where they live. The “new” school held under the trees is used as a women’s training center as well. The women learn literacy, nutrition and soap-making at the border and at Noemi Center in Kisantu where some of the migrants also live.

Traveling to the border from Kisantu is a challenge, whether going there to teach or to transport women and children back to the town with produce to sell. At the border Sr. Marizeta holds classes for women from both countries. Angolans are allowed to enter the DRC, but Congolese and the sisters are not allowed to cross over to Angola. No one comes to the border program when it is raining because there is no building. In the town of Kisantu the women do not come because they do not have umbrellas, and the streets are flooded or ankle deep with mud.

Scalabrinian Missionaries arrived in Angola, West Africa in 2000 after the war. I stayed with two of them in Luanda when on a site visit for the Hilton Fund for Sisters. One worked as director of the Jesuit Relief Services and the other in migration ministry for the diocese. The Missionary Sisters of St. Charles Borremeo (Scalabrinians) was founded in Italy to minister specifically to migrants. The first outreach from Italy was to the Italian immigrants migrating to Brazil at the end of the 19th century. Now the missionaries are in 26 countries.

Ministry to migrants and displaced people is a special vocation. Besides being challenged to adapt to all kinds of living conditions, poverty, languages and cultures, being with traumatized migrant persons and families could be the most challenging aspect of the ministry. In a recent interview by Duke University, Shelly Rambo shared reflections on such challenges. She said that witnessing suffering and staying in the space between death and resurrection with traumatized persons or communities is painful for ministers wondering whether life’s going to emerge from it. “To be able to stare death in the face and to live beyond it; and the grief and sorrow of not being able to understand what’s going on” forces us to cling to the promise (of the resurrection). It is a slow work of witness at the borders of faith itself.

[Joyce Meyer, PBVM, is international liaison to women religious outside of the United States for Global Sisters Report.]