Notes from the Field are reports from young women volunteering in ministries of Catholic sisters. The project began in the summer of 2015 when, working with the Catholic Volunteer Network, we enlisted four young women working in Honduras, Thailand, Ethiopia and the United States to blog about their experiences. The fall series presents two more women, both volunteering with sisters' ministries in the United States. This is the first installment from Sharon Zavala.

______

A typical workday year-round for Florida tomato-pickers starts at 4:30 a.m., when they wake up and prepare lunch in their trailer. At 5 a.m., they walk or bike to the parking lot or pickup site to wait for the worker bus. They board the old bus by 6:30 a.m. to go to the fields. The job may be anywhere from 10 to 100 miles away.

By 7:30 a.m., they arrive at the fields and begin weeding or waiting for the dew to evaporate from the tomatoes; they usually are not paid for this time. They begin picking tomatoes by 9 a.m., filling buckets, hoisting them on their shoulders, running them 100 feet or more to the truck and throwing the bucket up into the truck.

At noon, the farmworkers eat lunch as fast as they can, often with their hands, which are soaked in pesticides. Afterward, they return to working under the smoldering Florida sun. By 5 p.m., they board the bus again to return to their pickup site. They arrive between 5:30 and 8 p.m. and walk or bike home.

Immokalee, Florida, is where many of our great nation's tomatoes are grown — and they often are picked under grueling conditions. You most likely have not heard about this town, so let me tell you a little bit about it.

Immokalee is the center of the region's agriculture industry and is home to many immigrant and migrant families. These families work the vast fields, which produce a large amount of fresh produce sold here in the United States, including bell peppers, cucumbers, and about 90 percent of the nation's tomatoes harvested during the winter months.

Despite working in one of the most dangerous industries in the United States, the average farmworker earns just $7,500 a year with very few benefits. Farmworkers are often seen as tractors that harvest raw materials cheaply. As a result, for decades, Florida farmworkers faced human rights abuses, including systematic wage theft, sexual harassment, health and safety violations, and modern-day slavery.

In 1993, farmworkers in Immokalee from Mexico, Guatemala and Haiti began organizing to change this harsh reality. They began to meet weekly in a room borrowed from a local church to discuss how to better their community and their lives. In a few years, farmworkers had won industrywide raises of 13 to 25 percent and a newfound political and social respect from the outside world.

For the last 20 years, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers has been working to abolish modern-day slavery and fight for fair wages and treatment for all agricultural workers through marches and boycotts. The CIW began looking outside of Immokalee for allies who would help make demands for justice in the fields against some of the largest food retailers. Who are these retailers? Have you heard of Walmart? Taco Bell? McDonald's?

Farmworkers' daily experience of working in sweatshop conditions in the fields puts them in the best position to build movements and effect change. The main goal of the CIW is to build an understanding of injustice in the fields that leads consumers to act in solidarity with farmworkers. By supporting worker-led campaigns for better wages, respect and dignity, the CIW works toward a shared vision of collective liberation.

Over the past several years, through the CIW's Campaign for Fair Food and anti-slavery work, the coalition has evolved into an important national and statewide presence with forceful, committed leadership composed of young migrant workers forging a future of livable wages. I'm extremely pleased to be working with such a strong and determined organization as a Humility of Mary volunteer.

Every morning, I help members of the coalition on various tasks. Marches are one of the main actions the CIW adopts because they get a point across and can energize a large crowd. Marches require a careful division of roles and responsibilities, so I make sure we have enough signs and posters. I have gotten the chance to know the town well, so I design fliers and post them around Immokalee to make sure we have a good turnout at protests. A large part of my time is dedicated to helping Bryan, the education outreach coordinator, create presentations and handouts for colleges and universities about the CIW.

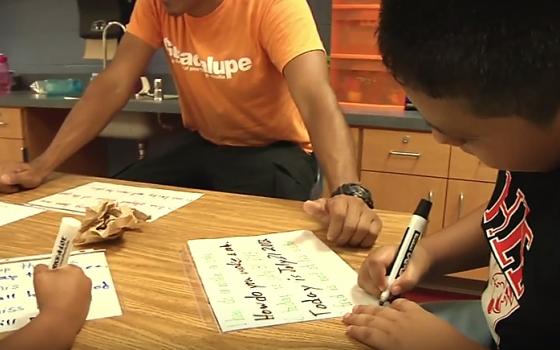

My work environment changes dramatically at 2 p.m., when I start working at the Guadalupe After-school Program, which provides at-risk Immokalee children in kindergarten through second grade the support they desperately need to catch up to their peers. Many students enrolled in the program were not afforded the benefits of high-quality early childhood education. Thus, they are working arduously, struggling to learn what many of their peers have already mastered.

"Research finds that by the time impoverished children reach middle school, they are over two and a half years behind their middle-class peers," the Guadalupe program's website states. "There are a myriad of reasons for this, but the end results are that children from lower socioeconomic families are less likely to be successful in school and, thus, in life. Without support, these children will continue to struggle and the achievement gap will grow wider with each year in school."

I spend two hours with my second-graders every day. Their enthusiasm and commitment to their education is contagious, and so is their energy. All they think about is playing tag, coloring and drawing, so little do they know about the issues adults face in their hometown. Most likely, their mom, dad, uncle, aunt, brother or sister works endless hours in the fields or in packing houses.

I have two high school volunteers who assist me in the after-school class every day. Despite their seven-hour school day, Aileen and Litzy still have the desire and energy to give back to their community. As soon as they enter the classroom, they go to the bin, pick up the activity of the day, and gather the kids around to begin. The class gets divided into three centers: writing/vocabulary, reading, and math. Litzy and Aileen each take the lead over a center and do the activity I planned for them. As the lead teacher, I create the daily lesson plan, which includes coming up with activities and games that will make the students engaged by learning and having fun at the same time.

The critical component that helps our class and program to succeed is commitment. Those who succeed in their world-changing endeavors have an unwavering, passionate, almost irrational commitment to their cause. My small group of Aileen, Litzy and me underscores the remarkable power of teamwork to transform, to inspire and to succeed.

[Sharon Zavala is a Humility of Mary volunteer in Immokalee, Florida. She has a bachelor's degree in environmental studies and Spanish from Allegheny College.]