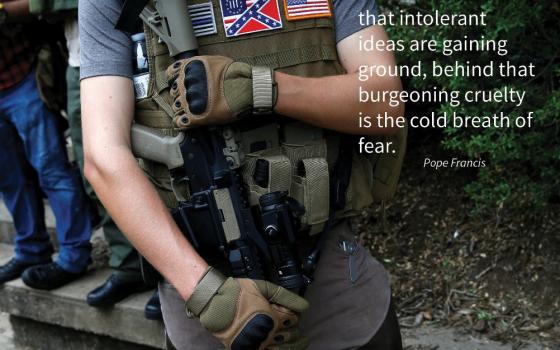

It was less than a week after neo-Nazis and other white nationalists brazenly marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, and just days after President Donald Trump equated the anti-protesters to the white supremicists themselves, then equivocated, then doubled down on the statements and said the whole thing was the fault of a free press, anyway.

A family friend, by all accounts a good person and upstanding citizen, posted on Facebook that henceforth she would no longer read any political statements, no matter what side. It was an effort to keep negativity out of her life and maintain a sense of well-being, she explained.

But while she was willing to shut out Nazi-types, their victims and their apologist-in-chief, she did want something: "Keep the babies and cute kitten shots coming, though."

There are at least 116 million Americans who don't have a choice when it comes to shutting out Nazis, the Ku Klux Klan, white nationalists and their allies. If you're someone other than a non-Hispanic white American, this isn't just politics; this is life and death.

Even though we are a non-Hispanic white couple, my wife and I joined the ranks of those who cannot view these issues as just politics 12 years ago, when we adopted our African-American daughter. It was then we learned, up close and personal, the white privilege we had been granted at birth.

While I have not experienced discrimination myself, I know what it is to look in your daughter's eyes and explain that she will have to work harder, behave better, go farther and put up with more than other people, including her white brother. Even then, sometimes it won't be enough.

I will soon get to have The Talk with her: not about the birds and the bees, but about how to behave around police officers, what to do if there is an issue, and how it's not just about courtesy and respect, but about life and death.

These are conversations no parent anywhere should have to have with their child. Not ever. Certainly not in America. And for anyone — anyone — not to be outraged about this should be inconceivable.

Imagine if you saw a headline that said citizens in your state were sentenced to prison terms that were three times longer than citizens in the state next door, though the crimes, the circumstances and their criminal records were identical.

You would be outraged, as you should be. But when black Americans are treated this way, whites too often stay silent.

We know this because the Sarasota Herald-Tribune recently published "Bias on the Bench," a landmark examination of the criminal justice system in Florida and the racial bias so inherent in it:

The Herald-Tribune spent a year reviewing tens of millions of records in two state databases — one compiled by the state's court clerks that tracks criminal cases through every stage of the justice system and the other by the Florida Department of Corrections that notes points scored by felons at sentencing.

Reporters examined more than 85,000 criminal appeals, read through boxes of court documents and crossed the state to interview more than 100 legal experts, advocates and criminal defendants.

The newspaper also built a first-of-its-kind database of Florida's criminal judges to compare sentencing patterns based on everything from a judge's age and previous work experience to race and political affiliation.

No news organization, university or government agency has ever done such a comprehensive study of sentences handed down by individual judges on a statewide scale.

I don't even have to tell you the results, because you already know what those reporters found, don't you? We all know. We have all known for decades.

And yet the majority of non-Hispanic white Americans, who make up 64 percent of the country, says these types of issues are not their problem.

"That's like running a red light in a white car and your ticket is $100 and running a red light in a black car and your ticket is $300," Florida State Rep. Wengay Newton Sr. told the Herald-Tribune. And because most of us drive white cars, we do nothing. At best, we shake our heads and go back to the pictures of babies and kittens.

Look at the newspaper's findings:

• When defendants score the same points in the formula used to set criminal punishments — indicating they should receive equal sentences — blacks spend far longer behind bars. There is no consistency between judges in Tallahassee and those in Sarasota.

• The war on drugs exacerbates racial disparities. Police target poor black neighborhoods, funneling more minorities into the system. Once in court, judges are tougher on black drug offenders every step of the way. Nearly half the counties in Florida sentence blacks convicted of felony drug possession to more than double the time of whites, even when their backgrounds are the same.

• Florida's state courts lack diversity, and it matters when it comes to sentencing. Blacks make up 16 percent of Florida's population and one-third of the state's prison inmates. But fewer than 7 percent of sitting judges are black and less than half of them preside over serious felonies. White judges in Florida sentence black defendants to 20 percent more time on average for third-degree felonies. Blacks who wear the robe give more balanced punishments.

Could you say "I don't want to read any more posts about politics" if people who looked like you were sentenced to double the time in prison as others?

In the few days after I first read the family friend's post, I wanted to shake her and ask, "Don't you understand?" This is not someone else's problem. This is not about black Americans and white Americans. It is about Americans, period.

White Americans' ability to say, "No thanks, but please pass the babies and kittens" is the very definition of white privilege, and it is also the very reason these problems continue to haunt us.

Yes, it's personal to me, and it's personal to millions of others, but it should be — must be — personal to all of us.

There is no middle ground here: You either oppose racism, whether it is as blatant as the "Unite the Right" marchers in Charlottesville with torches or as institutional as our court systems, or you are enabling it.

I love pictures of babies and kittens, too. But if we continue to choose them over the reality outside our computer screen, our society is doomed.

Remember, links, tips and accounts of the response to any crisis anywhere in the world are always welcome at [email protected].

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]