Even though I had visited Ethiopia a couple of other times before, being there during the Ethiopian Catholic and Orthodox Holy Week brought home very clearly how religious this culture is. I participated in rituals of each of the two rites, Latin and Ethiopian, and was even pleasantly surprised on my last day to attend a Jewish Sabbath ritual in an Addis Ababa synagogue. In my previous visits I had been primarily with sisters who were expatriates, either from the United States, Ireland or Nigeria, and thus we worshipped as Latin Rite Catholics. This visit awakened me to the reality of the Ethiopian Catholic church and how connected it is to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church through its culture, a culture also impacted by the Jewish roots of Christianity, particularly apparent in its food laws.

I experienced Ethiopia as an Orthodox Christian culture, almost monastic in tone. People engage in fasting and penance days throughout the year, but especially during Holy Week where there are long rituals of singing, praying and prostrating, particularly on Good Friday. On Holy Thursday I attended a liturgy that was more like our Western version with washing of the feet and lively music. Preparations for Easter were obvious all around us as we witnessed literally thousands of sheep being herded along the roads from the country into the city to be sold for the upcoming Sunday dinner.

On Holy Saturday night we saw clouds of white clothing wrapping children women and men on their way to church services that went on from 6:30 p.m. until early Sunday morning. The women's dresses were beautifully decorated with colorful designs woven into the fabric and their usually curly hair was also coiffed in unusual styles.

About 45 percent of the population of Ethiopia is Orthodox, 33 percent is Muslim and the remaining 22 percent of the people are a combination of Latin Catholic or other Christian denominations imported primarily from the United States, Jewish, and animist spiritual groups. The impact of Orthodox culture on the less than 1 percent Catholic population is very evident, and most of the local priests preside in liturgies of both Latin and Ethiopian rites. Some of the sisters we met were converts from Orthodox to Catholic faith, but still join their families in the traditional Orthodox liturgies as well.

What differentiates the Orthodox and Catholic traditions is their theology of Christ, his humanity and divinity. Put simply, the Orthodox believe that Jesus had two natures that combined into one God, with divinity taking precedence. Whereas, the Catholics believe that Jesus had two natures, true God and true man, uniting the two in one person. The superiority of divine over human is played out in the practices of Orthodoxy that include much fasting and penance. Because the government reflects the Coptic stance, the many feast and fast days throughout the year are celebrated by the entire population with official days off from work. Even though Orthodoxy is dominant in government, Catholics of both rites, along with Muslims and Jews, have lived together in peace in this country for centuries — they can recognize in each other the ancient spiritual connections. However, this does not discount conflicts that have arisen now and again.

Ethiopian Orthodoxy is a religion of liturgy and spoken prayers very much focused on the transcendent God rather than on the incarnational one of the Western church. Its penitential bent reflects how deeply the people feel a sense of unworthiness and need for atonement. Because there are no pews, people stand throughout the services. Some remain either just inside the door or outside of the church, a witness to their unworthiness. Usually only children, old people and monks receive Communion because sexual activity is seen as impurity among other adults, even though married. The emphasis on the transcendent rather than incarnational God is also noticed in the fact that community building, educational or social/political efforts to make the world a better place are not primary as they are in the Western church. Emphasis is on the mystery of a transcendent God and on personal salvation and atonement.

The Ethiopians are very proud of their monastic heritage, and the monasteries here are depositories of the ancient treasures of sacred literature — although these are practically inaccessible. Monks, both male and female, tend to be cloistered contemplatives. However, I do remember visiting an Orthodox convent some years ago where the sisters had a small kindergarten, something outside the norm. Monks, both women and men, basically live on alms or what they can produce for themselves.

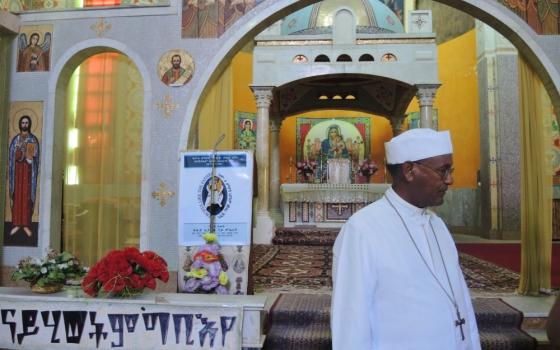

Some of the style of Orthodox liturgy and vocal prayer are also found in Ethiopian Catholic churches where celebrations continue from two to three hours. The Ethiopian Catholic church is in full communion with Rome although each have their own rites. An example of this is the Good Friday services that sisters participated in from 8 a.m. until 6:30 p.m. on empty stomachs. During this service, all the pews were removed from the church so there was plenty of standing room and space for numerous penitential prostrations. The day following, the Christians could hardly walk because of sore thigh and back muscles from the strenuous prayer postures.

The Ethiopian Catholic liturgies, similar to the Orthodox, focus on the presiders — priest, deacons and assistants (about five of them at a time) — who spend long periods behind curtains usually singing prayers of supplication and blessing. They remain separated from the people with the curtain symbolizing the distance between them as sinners and the holiness of God. There are short times when the curtains are opened and the priest prays with the people. It also seems to symbolize how God's holiness makes itself known in daily life. Lots of incense is used, again to symbolize the holiness and distance from God as it wafts upward.

Women and men are separated during the Catholic services as in the Orthodox churches. Liturgies are restrained, very unlike the celebrations of their southern African neighbors. I asked one of our drivers about African dancing or clapping in church. He said his family would be horrified to think of people dancing in church, although women do traditional African ululation at times of joy. Youth however, tend to like more action and so, as in our own country, some are turning to the evangelical style of worship.

This is a concern for the older generations who are fearful of losing their traditions. Even one of the bishops we spoke with expressed his worry that the Ethiopian Catholic church might be losing ground. The heritage is long and deep and the people are proud of it. The liturgy of Orthodoxy came from Alexandria, Egypt, its founding being attributed to St. Mark the evangelist. Missionaries from Alexandria evangelized Ethiopia in the Fourth century, but the native language, Ge'ez was used rather than Greek in order to bring the people along. Today, Ge'ez is considered a sacred language. The Ethiopian church liturgy eventually became independent of the Alexandrian format. The first bishop was St. Frumentius, a Christian who had served as minister of Axum, the historical capital of the Ethiopian empire and the first world nation to adopt Christianity.

Islam was introduced when the family of Prophet Mohammad was being persecuted around 613. A friend of the family was from Ethiopia, and he convinced the prophet to trust the Ethiopian king. Thus, the family felt it would be safest to move to a Christian country where the people were "of the Book" rather than stay in Arabia. Although some Ethiopians converted to Islam, Ethiopia remained officially a Christian nation.

So, when did Judaism find its way into the mix? There is little known history it seems, but some say it has been around for over 15 centuries. According to Atira Winchester, the Jewish community was never very homogenous and gradually lost contact with Israel. Because of isolation, the various groups developed unique sets of religious practices that were not considered typically Jewish. For example, an order of Ethiopian Jewish monks was founded in the 15th century to strengthen Jewish identity and resist Christian influence. The Jewish community has survived through many times of persecution and difficulty. In 1984 some of the community were able to go to Israel and others were left behind. It was with a group of these left behind that I was able to celebrate the Sabbath in their dirt floor synagogue the night before I left Ethiopia. There was a poignancy to the time with them, listening to their pining to go to Israel and be reunited with family members.

Even though Ethiopia has honored diversity over the years, there have also been movements to eradicate it. Today, for instance, the Oromo people, an ethnic group in southern Ethiopia, Muslim and Evangelical Christian, feel they are being persecuted by the reigning federal government that is dominant Amharic and Coptic. According to The Advocates for Human Rights, the government systematically oppresses the Oromo community. In November and December 2015, during what was considered a peaceful protest against the government for "land grabbing" of the community's properties for international development interests, some protestors were killed and others thrown into prison where they remain, being called terrorists.

New laws also make it difficult for Catholic missionaries from outside to work here. Anyone coming to work in the country even in pastoral work must have at least a bachelor's degree. This would include even bishops or cardinals from other countries. A Missionary of Charity I met was working in one of the care homes of their order without a nursing degree. When a visiting government official did not see such a badge on her habit, the sister was required to leave Ethiopia to obtain the needed degree before returning. A number of congregations of sisters from outside who once worked there left because of these kinds of obstacles put up by the government. On the face of it, it does not seem unreasonable, but native Ethiopian sisters do not have to follow the same requirements. I met one of them with only grade 10 education who was the head mistress of a kindergarten.

The current government has done many good things to develop the country as we witnessed in our travels. Even though the government claims to be democratically elected, people I talked with rolled their eyes and kept silent to any questions about how it functions. It is evident that Ethiopia has a complex history of combining religious and political values that can nurture cultural stability, but the religious emphasis on the transcendence of God can actually hinder the participation of the people in its total development. The dark sides of the religious culture can remain hidden to the view of outsiders, particularly in the realm of human rights. It was hard for me to learn about some of these dark sides, but Ethiopia still remains one of my favorite countries because of its beauty and unique and ancient religious culture.

[Joyce Meyer, PBVM, is international liaison to women religious outside of the United States for Global Sisters Report.]