You're about to read about a disturbing reality. In the U.S. and around the world, people are held against their will and forced to do sex acts or to work. It is modern-day slavery.

- How do you feel when you're forced to do something you don't want to do? What do you think of the person in control? How do you feel about yourself?

- Imagine feeling that way every day of your life with no hope of escaping.

(Unsplash / Roberto Tumini)

- Human trafficking is a secret social sin. The stories you're reading bring it out in the open and give people like you the chance to learn more about it.

- Catholic sisters in the U.S. and around the world are joining forces to work against human trafficking and raise awareness. The more you know, the more you can do to bring hope to victims of human trafficking.

Awareness fosters hope for often-invisible sex-trafficking victims in the Midwest

by J. Malcolm Garcia, Soli Salgado

Sr. Gladys Leigh still thinks about two women she wrote to in prison in 2015.

The survivors of sex trafficking had been accepted into Magdalene St. Louis, a program that helps women live free from abuse, addiction and prostitution. They served 12 months in prison for prostitution. Before their release, Leigh, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet - St. Louis Province and a volunteer with Magdalene, wrote them encouraging letters. They responded, seeking assurance that they would really be living in a safe, loving place.

They did not believe it was possible, Leigh said.

"'Can it be true?' they asked me," said Leigh, 70. "I said, 'Yes, yes.' I had to convince them. That really touched my heart. It showed me what they had lived through."

The two women Leigh spoke of are among hundreds of people trafficked yearly in the United States. According to a 2012 report by the Urban Institute and Northeastern University, sex trafficking accounted for 85% of trafficking cases identified by law enforcement, followed by labor trafficking at 11%. Cases involving both labor and sex trafficking totaled 4%.

From January to September 2016, 4,177 sex trafficking cases were reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline.

The problem has become so prevalent that in 2011, President Barack Obama designated January as National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month. National Human Trafficking Awareness Day is observed annually on Jan. 11. And in 2015, the Vatican named Feb. 8 the International Day of Prayer and Awareness against Human Trafficking.

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act, a federal law passed in 2000, defines sex trafficking as a commercial sex act "induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age." The definition is applicable to U.S. citizens and non-citizens alike.

"Sex trafficking is so covert," said Sr. Esther Hogan with Sisters of the Most Precious Blood of O'Fallon, Missouri. "People are not aware. This is so hidden. The women who are trafficked are vulnerable and invisible. People need to know this."

Of the 67 congregations that are members of U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking, about 25 are congregations from the Midwest. Midwestern states such as Missouri have become hubs for sex trafficking because of their central location, experts say. An extensive highway and interstate system with hundreds of truck stops and rest areas make it a prime location for sex trafficking.

According to the Polaris Project, one of the country's biggest anti-human-trafficking organizations, 79 sex trafficking cases were reported in Missouri in the first nine months of 2016.

"If we don't know anything about it, we can't do anything to change it," Hogan said. "How many people have heard of human trafficking? How many people know what it looks like? If we don't know what it is or what to look for, how can we help?"

Hogan's Sisters of the Most Precious Blood, along with members of the American Association of University Women and the Coalition Against Trafficking and Exploitation, started the St. Charles Coalition Against Human Trafficking in 2013. Hogan and her congregation have also launched the Yellow Butterfly Campaign to address human trafficking on college campuses.

Too often, sex trafficking can be identified or concealed by another crime, such as domestic abuse, said Emily Russell, victims advocate with the Missouri Sheriffs' Association.

"I deal with all kinds of situations," Russell said. "You work with someone, and you learn their parents trafficked them, or they ran away and met a pimp, or they're in a domestic violence situation. You see the manipulation. They are stuck and can't get out. It's not that difficult to consider whether the abuser is forcing women to perform sex acts for drugs."

Remote rural communities are spread throughout the Midwest and make illegal activity such as sex trafficking easier to conceal. But hubs of activity also provide opportunities to traffickers. Students in the Midwest's many universities and colleges may be drawn into trafficking because they live away from home with little supervision. The need to make money to pay back student loans can become a dangerous reason to accept what sounds like a money-making opportunity without fully understanding the consequences.

"Because of its central location and all the means of transportation available — planes, trains and trucks — kids can end up anywhere in the country in 36 hours from here," said Russ Tuttle with the Stop Trafficking Project and KC Street Hope in Kansas City, Missouri. "The gang level of sex trafficking is increasing [in the Midwest], as well. A trafficker can be any person who wants to exploit a child. It's a cash windfall for them, not for the child."

Based in Sioux City, Iowa, Franciscan Sr. Shirley Fineran — who belongs to the Siouxland Coalition Against Human Trafficking — said those in Iowa are "probably a little bit more trusting than those in other parts of the country." She said social media is a primary place where people are "groomed" for trafficking, as vulnerabilities can be exploited through connections and relationships made online.

Her goal is to open a restoration center for adult women, where she will house five to 10 women for up to two years. Fineran said the center will be a place where "women will go to heal [from] the traumatic experiences that they've had."

"We're going to help women live the rest of their lives as best they can with what they've experienced," she said. That process will include group and individual trauma therapy, as well as helping women acquire life skills that "most of us who have had a normal development in life take for granted," such as cooking, laundry and basic communication and problem-solving skills. The center also will help women who have children and need help regaining custody or reuniting with them, Fineran said.

(GSR graphic / Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Fineran will not require women to attend Bible study or prayer.

"It's very important that women do not experience religious control to replace the control that they've had," she said, adding that as a Catholic sister, she supports spirituality and will offer such guidance if women would like it. However, "sometimes I think people can use God and religion as a control, and that can be revictimizing, in one sense."

"With our restoration center, we're not looking to return women to something that was normal, because many of them never had a normal life. It's really to help them live the rest of their lives with what they've experienced."

How to spot trafficked individuals

As trafficking has drawn much greater public interest, myths associated with the crime have grown as well, said Bailey Patton Brackin, assistant director at Wichita State University's Center for Combating Human Trafficking. Though there are cases where someone might be grabbed off the street and taken somewhere to be trafficked, she said, that's a small portion of what trafficking cases look like.

"All cases are so unique, but most commonly, we're talking about a person who is exploited through an understanding of one of their vulnerabilities," Brackin said. "Oftentimes, a trafficker ends up building a relationship with a young person by finding out what they're missing in their life. Someone involved in foster care who doesn't have a family to rely on — that's a vulnerability where the trafficker can exploit and say, 'I'll provide that for you, I'll be that person.' It tends to be more of an involved process rather than someone who is picked up instantly and trafficked."

Traffickers often share a background of past trauma, she added, such as being involved with state custody, abuse in their own home, or an early exposure to drugs and alcohol. "The risk factors mirror; it's just that one becomes the exploiter, and one becomes the exploited."

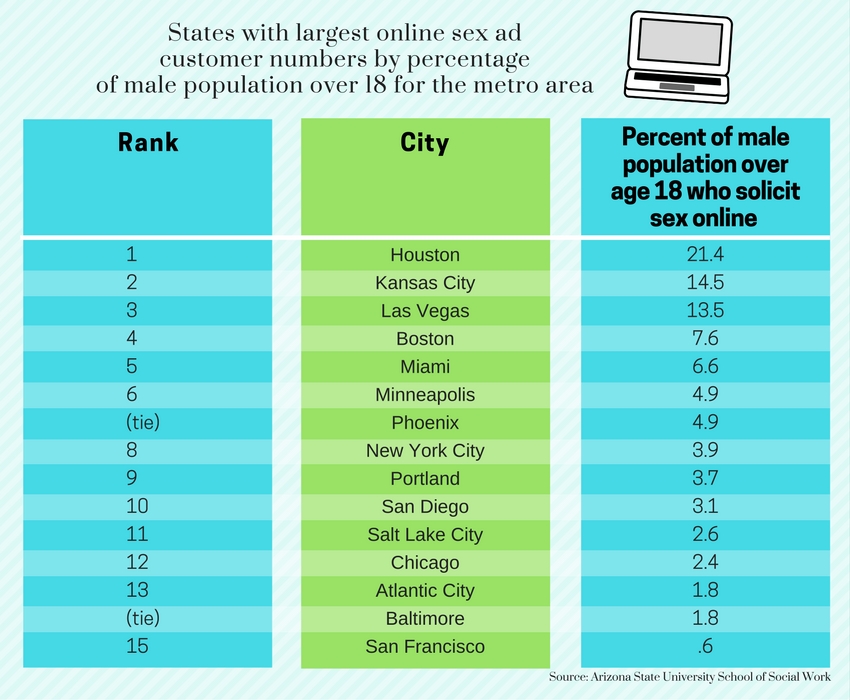

Tuttle of the Stop Trafficking Project blamed much of the trafficking trade on online advertisements for sex. A 2013 study conducted in 15 metropolitan city areas by Arizona State University's Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research found that one out of every 20 men over the age of 18 was soliciting sex through online ads.

"The demand is high," Tuttle said. "There's a need to educate people on what's going on on the demand side. They don't understand the ramifications in our area, the tragic and heartbreaking stories."

Sisters of many congregations throughout the Midwest are trying to teach people about trafficking.

In Belleville, Kansas, St. Joseph Sr. Margaret Nacke — who founded the Bakhita Initiative and later the coalition U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking — visits hospitals and motels, informing staff members of red flags indicating a trafficked person. These include:

- An inconsistent or scripted history or rehearsed responses

- Unaware of the current city

- Few or no possessions

- A striking age differential between the guests (for example, a young woman accompanied by an older man)

- Possesses items he or she can't afford or is carrying large amounts of cash

- Lives with his or her employer

Like Nacke, Humility Sr. Anne Victory is working to educate hospital staffs throughout Cleveland. Law enforcement and social service agencies had mentioned to her that hospitals should know how to care for victims, who often wind up in them.

A nurse told Victory that she thinks hospitals treat people they suspect are trafficking victims but don't know how to handle the situation. So Victory, a nurse and educator, put together a training film for health care facilities in the region with help from hospitals and Sisters of Charity Health System.

Already, 600 people have seen the film. Victory, who is education coordinator for the Collaborative to End Human Trafficking, is working to fulfill requests for similar versions of the film for other regions of the country.

She also plans to train school staffs and those in immigration refugee communities, which have unique needs and cultural understandings.

"The thing is, if you've seen one [case of trafficking], you've seen one," she said. "There are similarities, but every situation is different, and every situation is tragic. ... There's a need to listen to them, to hear what they perceive their needs to be rather just presume we know."

Christine McDonald, program director of Restoration House of Greater Kansas City. (Provided photo)

"Maybe they will remember what love was'

Christine McDonald, 48, an advocate for sex-trafficking survivors in the St. Louis area, was trafficked both as a teenager and an adult. She said too many people think trafficking happens overseas and involves international kidnapping, not aware of incidents closer to home.

McDonald was a 15-year-old runaway when a man gave her a job selling flowers in Oklahoma bars in the mid-1980s. He gave her a room and a fake ID. She calls this period "being groomed."

After a few weeks, the man left her with another man who owned strip clubs. Only later would McDonald realize she had been sold.

The second man raped her. He had McDonald dance in the clubs and he took what she earned. She relied on him for a place to stay. She began using drugs to prepare herself for what would happen after she had danced and was given to men for sex. Once she became addicted, she stayed to be able to get more drugs.

"What was I to do? Where was I to go?" McDonald said. "Call the police? Trafficking was not even a term then. You have guilt and shame. You're trafficked before you are an adult, but then you turn 18 and prostitution is a crime, so now you're a criminal. That becomes a jacket that prevents you from getting legitimate work, a place to live, a new life."

For a survivor to even discuss trafficking carries risks of further exploitation by people who mean well, McDonald said.

"For some people, a survivor's only value is in their story," McDonald said. "It makes it that much harder to move beyond being a survivor and creates a kind of voyeurism."

Today, McDonald is the program director of Restoration House of Greater Kansas City, which assists survivors of sex trafficking by offering shelter and counseling. The house provides for physical needs, and offers trauma and addiction therapy, education and job skill training, all intended to help victims heal and acquire the resources they need to lead fulfilling lives.

Leigh, the volunteer with Magdalene St. Louis, has worked with McDonald. She said McDonald's stories and those she has heard from other survivors are "eye- and heart-opening."

In 2011, Leigh began volunteering with The Covering House, a St. Louis nonprofit that helps sexually exploited girls through counseling, shelter and other supportive services.

St. Joseph Sr. Gladys Leigh (Provided photo)

One 13-year-old girl she served stands out. Leigh and the girl watched movies together. One movie prompted Leigh to say that the lead character had a marshmallow heart.

The girl wondered what kind of heart she had and asked Leigh.

"You have the same," Leigh said, "but one covered with chocolate." The girl understood that to mean that the chocolate was a shield to protect her heart.

She had reason to protect it, Leigh said. The girl loved her mother and "would have given anything to hear her say, 'I love you.'" But the mother would not or could not. Leigh will never know.

Leigh saw the mother in court for a hearing on the girl's custody case one afternoon. The mother did not want her daughter. The girl called to her. Her mother ignored her. The girl called to her again, and again the mother ignored her.

"Mom, can you hear me?" the girl shouted.

Still the mother ignored her. After the hearing, the girl, holding Leigh's hand, ran after her mother. "Go away," Leigh recalled the mother saying. "Go away." The girl wept.

"I am learning not to be judgmental," Leigh said. "I won't judge the mother. The mother was very petite. She looked almost like another child to me."

Leigh does not know what happened to the girl. She was gone one weekend when Leigh came for her volunteer shift.

"I don't ask questions," she said. "I pray for those who leave. Maybe they will come back. Maybe they will remember what love was and be willing to try again for a new life instead of remaining in the old life, the only life they've known."

The importance of human dignity

Driving through Toledo, Ohio, at night, Notre Dame Sr. Francis Marie Penwell would scout the streets with a few sisters, looking for lone, potentially trafficked women.

"One time, we met a girl who told us that we saved her life that day because we stopped. We not only stopped, but we said, 'What can we do for you?' " Penwell said. "She later said, 'I've been on the streets for 13 years, and not one person has ever reached out and said, "What can I do for you?" until that day.' It moved our hearts, too, knowing that that whole day of going out, we only reached one person, but that person was very vital when it came to needs."

Penwell is involved with Rahab's Heart, a resource in Toledo for women trapped in prostitution. About 10 women invited from the streets join the biweekly dinners and share their stories, the others "reaching out or just listening to their needs."

The trafficked women "can relax there; they're not on the jobs," she said. One time, Penwell brought a friend to join the women at Rahab's Heart for dinner, and her friend couldn't tell the volunteers apart from the trafficked women.

Sr. Marlene Weisenbeck, with white hair, attends the White House Advisory Council for Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships in 2013. (Provided photo)

People often don't think about human dignity when they think about these types of problems in the world, said Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration Marlene Weisenbeck, who started the Task Force to Eradicate Modern Slavery in 2013. Weisenbeck, who lives in La Crosse, Wisconsin, was asked to participate in the White House Advisory Council on Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships in 2012.

She was instrumental in enlisting Wisconsin's two U.S. senators to co-sponsor legislation that would require multimillion-dollar corporations to state in their annual reports whether their products are the result of forced labor. Another bill about the investigation of child abuse reports said that children who are engaged in prostitution should be immediately considered trafficked individuals.

"'Blessed are those who care of the prisoners,' and human trafficking victims are definitely prisoners because their freedom has been taken away; others are controlling their lives completely," Weisenbeck said.

"The Holy Spirit works through people, and we hear the voice of the Holy Spirit through the voices of those who suffer."

This article looks at different ways to work for change regarding human trafficking.

- What kind of feelings do you have for the victims of human trafficking?

- What most surprised or disturbed you about trafficking and those it affects?

- How would you respond if you knew human trafficking was happening in your community?

When Jesus began his ministry, he read an important passage of Scripture and made a bold statement:

He came to Nazareth, where he had grown up, and went according to his custom into the synagogue on the sabbath day. He stood up to read and was handed a scroll of the prophet Isaiah. He unrolled the scroll and found the passage where it was written:

"The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring glad tidings to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, and to proclaim a year acceptable to the Lord."

Rolling up the scroll, he handed it back to the attendant and sat down, and the eyes of all in the synagogue looked intently at him. He said to them, "Today this Scripture passage is fulfilled in your hearing."

- Why is it important that Jesus shows concern for captives and other hurting people as he begins his work among us?

- Slavery was common to the people that Jesus, and Isaiah before him, spoke to. Is the need to proclaim liberty to captive people still important today? Why?

- What do you think Jesus would say or do to those who enslave people through human trafficking?

Since the time he was called to lead the Church, Pope Francis has spoken strongly against human trafficking. In his Message for the 2015 World Day of Peace, he wrote:

"I urgently appeal to all men and women of goodwill, and all those near or far, including the highest levels of civil institutions, who witness the scourge of contemporary slavery, not to become accomplices to this evil, not to turn away from the sufferings of our brothers and sisters, our fellow human beings, who are deprived of their freedom and dignity. Instead, may we have the courage to touch the suffering flesh of Christ, revealed in the faces of those countless persons whom he calls 'the least of these my brethren.'"

- A scourge is an injury, like a wound inflicted with a whip. Pope Francis reminds us not only of the suffering Jesus endured for us but of Christ's teaching that when we help hurting people, we help him. How do you respond when a person is wounded?

- The Bible teaches us that we are all parts of the body of Christ, and that when one part of the body suffers, all suffer with it. How does the pain of human trafficking hurt people beyond its victims?

Just as sex trafficking is a hidden problem, many of the programs and homes that support its victims operate somewhat secretly. Their locations aren't publicized to protect the survivors from those who once victimized them. Unlike many facilities that feed or clothe people in need, these are likely not appropriate places for young people to volunteer. You can learn more about what Catholic women religious in the U.S. are doing to fight against human trafficking from their website: U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking.

- Reach out to the facilities or congregations of sisters linked to this story and see how you and your family, church or class can help them

- Pray for the sisters, their volunteers and the trafficking survivors they serve.

- Awareness is key to identifying human trafficking victims and getting them the help they need. Learn more about the signs that someone is being trafficked and share this information with your friends and classmates.

- Report suspected human trafficking by calling the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 or texting "help" to BeFree (233733).

God, give us the courage and understanding to learn more about human trafficking and doing all we can to free and protect its victims.

Grant them hope in their captivity until one day we, your people, might proclaim their liberty.

Amen.

Tell us what you think about this resource, or give us ideas for other resources you'd like to see, by contacting us at [email protected]