1.

I am driving through the Northwoods of Wisconsin, talking to a friend, a man I know very well, on the phone. Tall, snow-covered pines line the ditches; gray overcast hovers. The man and I are catching up, chatting about our lives. The tone of his voice becomes shameful, reluctant. My gaze moves over the wide, open road ahead as I hear his story. His words come slowly as he admits that he is on a leave of absence from his job after he said a racial slur while in a casual conversation with his colleagues. He is not allowed to work or earn money; he is expected to apologize to every one of his co-workers personally. He is humbled, broken. And yet he remains surprised. "I don't know why I said it ... I'm not that kind of person ..." I keep driving. I don't know what to say.

2.

I am a newly professed sister teaching at a high school on Chicago's South Side with a mission to serve African-American boys. I am learning to listen. I listen to my students when they explain why they need an extension on their assignments, when one says he spent the whole night in the ER with his cousin who was shot as they played ball in the park. I listen to my students when they come to class without their bookbag after being mugged on the way to school. I listen as my students tell me how they were still in elementary school when their parents started telling them how to avoid arrest or being shot by the police; their skin color meant they automatically fall under suspicion. I begin to become suspicious of my education and teacher's training; I wonder how protected I have been from the experiences of my black brothers and sisters.

3.

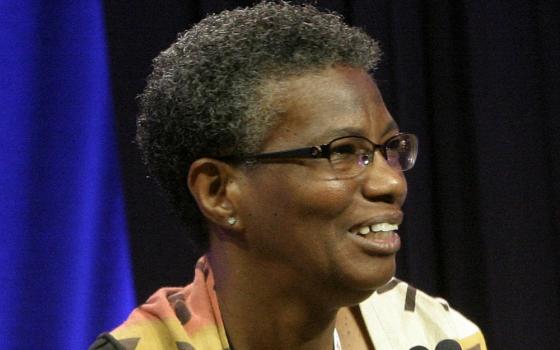

I am 18 years old and far away from the mostly white Iowan farming community where I grew up. I am visiting a convent for the first time in my life. I am meeting many white sisters who feel like my aunts, who are much like the woman I hope to be: deep, prayerful, smart, socially conscious. I am sitting in a basement dining room in a large motherhouse, eating a simple supper and meeting a black sister for the first time, a highly intelligent, witty and engaging woman named Sr. Patricia Chappell, a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur. I learn about church history from her, and I leave the conversation changed. Yet, I am unsure why Sister Patricia had such a big impression on me.

4.

Whether I like it or not, I participate in the evil of racism every time I enjoy my white privilege. When I feel the tinge of excitement over seeing a "run-down" neighborhood flipped into an area with funky shops and remodeled homes (that's what gentrification is), I'm ignoring the plight of the poor. When I savor easy access to healthy food and transportation without anger for the lack of attainability my black and brown brothers and sisters have of such basics, I'm failing to love. And when I experience nothing but respect and kindness from police officers and assume it's everyone's experience, I'm turning away from the Truth. (Words I wrote in an essay in 2016: The skin I didn't ask for: Bemoaning my white privilege and the evil of racial violence.)

5.

This is a true story:

6.

I am alone in a large stairwell in a Catholic retreat center. I have wandered away from the event that I am attending, in a gloomy mood and needing some space to myself. I am clinging to a giant crucifix hanging over my head, crying. I lean my whole body against the orange stuccoed wall. My head and hands crush into the corpus, the cross. Tears soak my face, coat my glasses; my nose drips. I ignore the mess that I am becoming. I ignore any sense of time that could make me end this cry too soon. I cry for an unknown amount of time. When I leave the stairwell, I don't feel better, but I am changed.

7.

Source: Facebook / Ellen Tuzzolo

8.

I have been conditioned to think that I should help the poor, the marginalized, the people of color. I have been taught to go on mission trips and to do service projects because the "less fortunate" need my help. I have been taught to fear change. I have been taught to preserve my culture, my traditions. I have been taught to take pride in who I am, in my whiteness. I have been convinced that if I see a person of color in trouble, that I ought to rescue them, jump into the situation, help them, advocate. I have been mistaught; I see now that it is not my job to save or redeem. I have to notice how my whiteness can be destructive and come out sideways. I have to admit that racist and white supremacist attitudes are deeply engrained in me. I have a lot of reasons to repent. I have to do my homework and notice when I am sinful, ugly. I have to repent.

9.

I am sitting at a table next to another Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, scribbling notes on the back side of the racism handouts I found in my folder. Exhausted and dazed from a day of travel, I only catch some of the words of warning coming from the sister speaking at the microphone.

In the room are more than a hundred people from throughout the United States — sisters, partners and employees who are the justice promoters from various communities of women religious. It's March 24, 2019, and the first day of a three-day Justice Conference for Women Religious convocation near the St. Louis airport.

The warning coming from the sister speaking at the microphone, Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Anne-Louise Nadeau, is a message rooted in her experience of working side-by-side with Sr. Patricia Chappell for two decades to confront the sin of racism and its destruction. "If I would have known how much transformation would cost ... I'm not sure I would have said yes ... but I like the woman I am becoming ..."

Standing up against racism lost her relationships, trust, support, credibility. People don't always believe her. She has been unwelcomed, shunned, avoided, ignored. Some people who were once her friends now view her as a new threat. And again and again, she has learned to do her homework: to become more self-aware, to realize how she participates in the systems of oppression. She must change her attitudes and her views, her behaviors.

Living the Gospel and standing up for justice tends to be dangerous, risky; the price for being a white ally and standing with people of color can be one's life; being a student of history has taught me this. Plus, following Jesus ought to cost our lives. His acceptance of the cross shows us the way.

"If I would have known how much transformation would cost ... I'm not sure I would have said yes ... but I like the woman I am becoming ..."

10.

"We have to stop demonizing people and realize the biggest terror threat in this country is white men, most of them radicalized to the right, and we have to start doing something about them."

—Don Lemon

"From 2012 to 2017, the number of actual white-supremacist attacks more than doubled, from 14 to 31. ... The Anti-Defamation League attributes 73% of extremist-related killings in the U.S. from 2009 to 2018 to the far right."

—Charlie Campbell

11.

There is a major cost for shrinking from naming evil. Evil creeps through every society and crawls into the hollows of our hearts, where our deepest fears lie dormant. Evil crawls into the places where we hold our dreams and desires, cling to pride and comforts and subtly shifts our understandings, gets us to justify our destructive behaviors. If we see how evil lurks, ready to convince us of lies, then we might be able to name it, confront it in ourselves, each other. If we name the evil then we can have power over it; we can change.

12.

"If faith is the evidence of things unseen, then perhaps disillusionment is the evidence of things we see with our own eyes."

—Natasha Oladokun

13.

The cross is an intersection of powerlessness and power. From the cross of Christ, I learn to not fear powerlessness, and how to let God's power reign. I long to imitate Jesus. I hope to become powerless so that others can become more powerful. I wonder if there will ever be a day when every white Christian will imitate Jesus and fearlessly avoid the temptation to protect their own power.

14.

Twenty-one years after my first visit to a convent, I meet Sr. Patricia Chappell again at the Justice Conference of Women Religious convocation in St. Louis. As she teaches, she enlivens the room and reminds us how to be sister to each other, how to stand with one another and how to walk alongside with love.

She helps us sing from our hearts, our souls.

There is a balm in Gilead

to make the wounded whole.

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sinsick soul.

After the music, Sister Patricia speaks and reminds us that we all are moving together. "We are that balm in Gilead," she says.

The music of transformation continues.

[Now on staff at Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center in northern Wisconsin, Julia Walsh is a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, a Catholic youth minister, a committed social justice activist, and a graduate of Catholic Theological Union. Her award-winning writing has appeared in America, Global Sisters Report, Living Faith, and PILGRIM Journal. Visit her online at messyjesusbusiness.com and follow her on Twitter @juliafspa.]