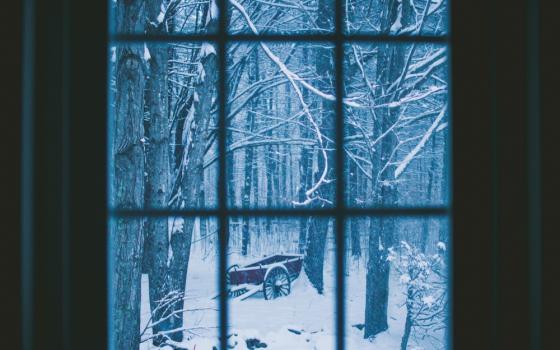

My week alone is coming to an end. I've been in hermit mode, making a retreat in a cabin in the woods. It's truly been a grace to be here, to escape from my normal routines and offer some focused energy to a big project. The solitude became a shelter; the quiet like a balm to my restless heart and mind.

While I separated from others, a great tension of my religious vocation was exposed as well: solitude versus community.

It seems that somewhere along the way I was taught to fear the solitary life, to associate lonely people with a haunted energy that compels others to reject, fear and avoid them — as if loneliness were a contagious sickness.

Many of the stories that I devoured as a child contained pictures of recluses living in an old, rundown house on the edge of town, feared by the whole village. The image repeats itself in so many books and movies that I can't even place it in one particular story from my childhood. I also have vague memories of my childhood playmates whispering rumors about the people who lived alone in rundown houses in our little town. Now I wonder why I learned to be suspicious of recluses, of people who were more isolated and nonconforming.

Children could be taught to be suspicious of an isolated life because it can be unhealthy. A lot of us select separation as a way to avoid dealing with life. Although we rarely isolate ourselves in the corners of society so much anymore, we all fall into patterns of escape. Today, most often our escape patterns are found in the tangled webs of life online.

By every swipe and scroll, we can ignore the depths of feelings and doubts, the terrifying powers of silence and vulnerability. Our devices can make it easy to tune out what is stirring within. Yet, our inner life invites us to tend to the churnings of our hearts and minds. Such tending is a path to God, a way to become the person we were made to be.

Although this is the invitation, a lot of us have the habit of hovering over screens and devices. We often enter into virtual drama instead of the trouble of being truly present to the living creatures and beauty surrounding us. Presence is the most radical thing we can offer to one another now, when we are tempted to checkout and ignore the challenges of feeling and relating. We'd rather avoid it all and feel a rush in our brain.

It is too easy to become obsessed about counting our comments and likes, as if these points prove that these behaviors — oversharing and publicizing of the ordinary — are worthwhile and meaningful. With each scroll and swipe, we feel the fleeting pleasure of being known, recognized — of belonging. Sometimes social media feeds us with a strange sense of fame.

What's really going on, though, is that dopamine is rushing through our neurons with each online interaction, creating a buzz of positive energy. This is the same sort of bliss that bubbles in people when they experience the pleasures of spousal loving, human touch or affection. These sensations are addicting, rewiring our brains to get us coming back for more.

Even more problematic, is that the buzz in our brains widens the gap between God and our hearts.

This trend concerns me. Could it be that wherever we place our energy and devotion, whatever we click into hoping to find satisfaction, has become a new god — a false path to holiness, an idol? Is this why the Vatican encouraged us Catholic sisters last year to be cautious about how we behave online?

If we're always plugged in, we're never truly alone, and solitude can be a path to holiness.

Somewhere along the way, thankfully, I also learned to associate solitary folks with wisdom. Accompanying the recluse we feared was the repeated motif of elders hidden away in quiet cabins, surviving off the land, living lives of simplicity and solitude — that shaped my imagination. I heard of saints and mystics, of the desert fathers and mothers, isolated in caves and communing with God.

As a young adult who deeply desired to be close to God, I was drawn to the ideal of a hermit's ascetic life. The image captured so much of my imagination, I felt in awe when I encountered sisters that were living in this way.

Once, I tromped across the muddy woods to visit a sister who lived alone in a cabin, surrounded by woods. I carried with me my questions and struggles, my hopes that she would instruct me in the spiritual path and teach me some great lesson.

As I approached the screen door and saw a little sign announcing the name of her cabin — Peace — decorated with dewdrops and the gentle design of a spider web, I felt shivers of wonder. This woman, living alone in the woods, likely knew God very well. Her solitude and prayerful life was a service for us all. I admired it and longed for it, but I didn't understand it.

A few years into religious life and before my lifelong commitment, I couldn't stop wondering why I was called to be a sister, why it was a good fit for me. I wanted to be a mother, I wanted to be a wife — but every time I would daydream about these possibilities, I would hear a deep "No" inside me. Why?

My spiritual director at the time, a Franciscan priest and psychologist, patiently listened to my questions. I really didn't understand who I was or why I was living this unique lifestyle, and the not-understanding was causing me agony. I was unclear about my purpose and direction; it felt like a struggle to find joy and contentment as a sister.

At the time, I was teaching high school on the south side of Chicago. Over Christmas break, I decided to go on a retreat. I drove north to a retreat center in Wisconsin's woods and quickly settled into a rhythm of meditation, walks, reading and journaling. In the silence and away from my typical routine, I prayed with the possibilities of my life. I imagined myself as a mother and wife. I saw myself looking happy, extending a lot of warmth and care to adorable children and creating a strong, healthy family.

I also imagined myself trying to do as I am now — getting up in the morning and grabbing my coffee and turning all my attention to God. I saw myself sitting in my prayer chair and lighting a candle and reading my psalm book. I heard a cry in the background and imagined a toddler climb into my lap. I knew it then, as certain as I know that I am alive: If I became a mother, my prayer life would have to be put on hold.

After my retreat, I was excited to tell my spiritual director about my new discovery. When I told him, he nodded. Did you know this? Why didn't you tell me? He grinned and gazed back at me with all sorts of kindness. I was waiting for you to realize it yourself.

I was glad to understand why I was called to be a Franciscan sister. Although walls of selfishness can block me from being my best self, solitude is an important element in my path to communion with God. And, in this, I am not so unique.

Just as each of us is made for togetherness, we all are made for solitude. This is a sacred tension of religious vocation.

There are good reasons for being alone: to pray and work, to encounter Christ and to learn the truth of who we are who we are called to be. Fostering reflective thinking skills, tracking your thoughts and behaviors, paying attention to what draws and attracts you, working with God on a big project — and then talking to God about all these things — can be the best teacher, the wisest elder we can visit in the woods.

You do not need to be afraid of solitude. Have courage and put down your device. Turn your heart and mind toward God. Let the silence teach you who are, and who you are meant to be.

[Now on staff at Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center in northern Wisconsin, Julia Walsh is a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration, a Catholic youth minister, a committed social justice activist, and a graduate of Catholic Theological Union. Her award-winning writing has appeared in America, Global Sisters Report, Living Faith, and PILGRIM Journal. Visit her online at messyjesusbusiness.com and follow her on Twitter @juliafspa.]