Many of our friends and family back home in the U.S. and continental Europe think that founding a Cistercian monastery on the island of Tautra in Norway is taking a bit too literally Jesus' command to go out to the ends of the Earth. Though the temperatures are actually less extreme than at our motherhouse, Our Lady of the Mississippi Abbey in Dubuque, our latitude of 63 degees puts us 3 degrees south of the Arctic Circle and 8 degrees north of Moscow. This provides a very interesting experience of living on the edge of land and sea, civilization and wilderness, light and darkness. So close to the North Pole, we have 20 hours of daylight in the summer, and 20 hours of darkness during the winter months.

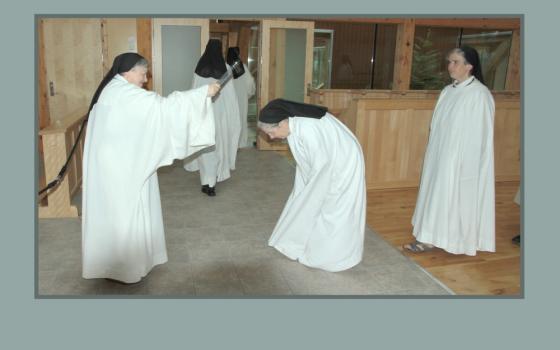

Our vocation as Cistercian nuns means that we live a sacramental life, celebrating the Eucharist every day and living under the same roof as Jesus in the Tabernacle. Each sister approaches the sacrament of reconciliation as often as she feels necessary, and we try to live forgiveness and reconciliation with each other each day. We sing psalms in church seven times a day and try to treat even the tools of the monastery with the respect due the vessels of the altar. Every evening at the end of Compline, our prioress sprinkles us with holy water as a reminder of our baptism and a blessing as we enter the night and the Great Silence.

Recently classmate Bill Shullenberger shared with me his wife Bonnie's memoir. Bonnie, an Episcopal priest, was a spiritual friend I never actually met. We corresponded sporadically until she died unexpectedly in 2009. In 1988-89, her final year in seminary, Bonnie was serving as chaplain at St. Luke's/Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan. She was on 24-hour call, and late one night, she was paged to visit an infant who had survived her birth with a collapsed skull and other severe congenital effects, just born and just barely alive. Her parents wanted her baptized.

Bonnie, gloved and gowned, went into the neonatal intensive care unit where Stephanie lay. Her eyes were fixed and wide open. Not knowing whether Stephanie was even alive, Bonnie blew gently on her eyes. She blinked. Bonnie asked for a bottle of sterile water. And as a nurse held a prayer book, Bonnie blessed the water, poured it into her gloved hand and baptized Stephanie, "In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit."

As the water touched her head, Stephanie shuddered. Her small dark eyes met mine, and suddenly I saw eternity open. For a second that seemed to last forever, I saw this wounded child as God must have seen her: beautiful and whole. Her life became to me infinitely precious. There was nothing in my life that I had ever done that mattered so much as what I was doing right then, and there was no child more beloved of God than this child.

Bonnie made the sign of the cross on Stephanie's forehead and then went out of the room to pray with her grieving father. Stephanie died an hour later.

As Bonnie later reflected on this experience, she wrote:

It occurred to me that God sees me as he sees the Stephanies of this world — beautiful and whole. . . . . God loves to see us as he meant us to be, and as we will be when we are with him at last. This is the God who loved so completely that he took it upon himself to join us funny and foolish creatures made in his image, so that all creation could be made new . . . [T]here is no trouble into which God's grace cannot enter, and there is no event that God's love cannot ultimately turn to the good.

This is what baptism does for us: enables us to see one another as God sees us: beautiful and whole. If we can live with this vision and insight, the hard moments of reconciliation become so much easier.

We, the baptized, are privileged to live a sacramental life. We live on the knife edge between life and death, at the intersection of time and eternity. We can look into one another's eyes and catch a glimpse of love that will last forever.

I have a theory about déjà-vu experiences. They are moments when, for some reason, we are allowed to step into eternity, beyond the bounds of time, when all "moments" are present. I really have met that person before, or traveled to that place. I think it will be like this when we finally step over the last edge of our life, and discover the new love that we have always known.

[Sr. Sheryl Frances Chen was assistant editor of U.S. Catholic magazine before she entered the monastery to join the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO). Now she is chantress and Saturday cook at Tautra Mariakloster on an island in the Trondheim fjord.]