Judith Odero, now 34, remembers what it was like to knock on the door of the principal's office of the St. Theresa's Gekano Girls School in Kisii, Kenya, hoping that the School Sisters of Notre Dame would give her a chance at an education and a future.

Odero had already started studying at the high school, but knew she would be unable to pay for her last two years. She came from an impoverished family of seven, and her parents could not afford school for all of the children. The two boys were given first priority.

"I feared dropping out of school because I could easily become a victim of early marriage and not realize my dream of becoming a teacher," Odero said. "Most girls who did not attend school in my village were married off to fetch a bride-price."

That was in 1997. When the sisters visited her home, 60 kilometers (about 37 miles) away from the school, and determined that Odero truly needed financial support to continue studying, they decided to waive her school fees. But the sisters could not have guessed the impact of educating that one student.

In large rural families in Kenya, there is cultural pressure to educate the boys. That's because, when girls get married, they go stay with their husbands while boys remain in their original home to take care of the parents and continue the family name.

However, Odero had the passion and desire to finish her education, refusing to let that custom stand in her way. She approached Sr. Jeanne Goesseling, who was then the principal of St. Theresa's in Kisii, located in western Kenya.

Odero always wanted to be a teacher, and the offer of a scholarship, combined with the school motto, "Enter to learn, learn to serve," inspired her to work with disadvantaged children.

Odero got married after finishing her education and moved with her husband to Mathare, a large slum in eastern Nairobi, where he had landed a job. Living in the urban slum, she realized so many people in her immediate neighborhood needed an education, just as she did as a teenager. She volunteered her services at CASO Upendo Academy in Mathare as a community worker for five months. There she learned how to approach parents and persuade them of the need to educate their children.

But it wasn't enough to volunteer. With her husband's support, Odero decided to go to back to school to acquire skills and knowledge that would enable her to best serve these kids.

After four years at the Migori Teachers Training College in western Kenya, Odero decided to come back and start her own school for children in Mathare.

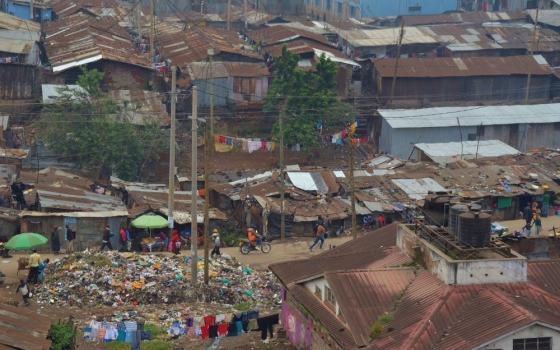

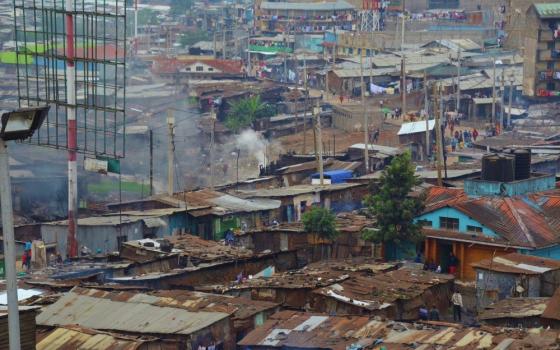

Mathare is the second largest slum in Nairobi, two square miles and home to about half a million people. By comparison, a similar number of people live in Baltimore, Maryland, which covers 81 square miles. Because of this congestion, survival is a daily battle against the backdrop of disease, crime, drug abuse, child abuse, prostitution and lawlessness. Sending children to school here is not a priority.

"I was always affected seeing children of school-going age loitering around," Odero says. "I'd see them playing in the dirty trenches full of water emanating from burst sewers. I'd see children, especially young girls, carrying 10- or 20-liter containers [up to 5 gallons] of water on their backs, some on their heads, as they helped their mothers to fetch water. This reminded me of my own situation. I feel their struggle. I know they have the potential and interest to learn but no support."

The streets of Mathare are full of garbage, and contaminated water flows on the road. The government does not pay much attention to the poor drainage system or in keeping this place clean. Residents pay 5 cents to use the toilets and bathrooms until they are closed at 9 p.m. At night, people use plastic bags as toilets. Since there is no trash removal, they have no choice but to throw the bags out on the streets.

Mathare is an informal, unsanctioned settlement of people from rural areas in search of under-the-table wages for work in the city. In the early 1960s, residents sought to improve their settlements by establishing their own schools, community organizations and advocating for services with the then Nairobi City Council. However, the council never recognized the settlement.

In the first years after Kenyan independence from Britain in 1963, the city council regularly demolished structures and failed to provide water or refuse collection in the area. Demolitions no longer take place because the government has not established relocation centers for displaced persons.

Mathare can be downright dangerous if you are unfamiliar with the area. Visitors are advised to leave their valuables behind due to pickpockets, and even journalists and donors need protection from a resident.

A school for Mathare's children

Odero started Destiny Junior Educational Centre in 2013, armed with only an idea. She had no funds to rent a room or to buy teaching materials. A friend donated a room, learning and reading materials, and food, which enabled her to begin a pre-school with about 40 pupils. She later got support from Mercedes Dancan, a Canadian donor recommended by a friend who was working at the United Nations office in Nairobi.

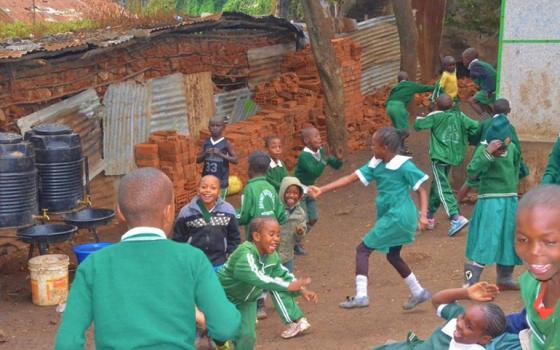

Odero and eight community volunteers walked from door to door, approaching parents whose school-age children were at home, either because their families needed them to work or they lacked money for school fees. Odero convinced parents to allow their children to try school. News about her school soon spread. In three years, the number of pupils attending kindergarten to eighth grade has increased to nearly 400.

Odero charges a minimal fee for school because many families here survive on less than a dollar a day. She feeds the children and encourages them to take the leftover food home. "When they take home food, I am certain that the following day they will come back strong and ready to learn," she says.

The children also have extracurricular activities, such as learning songs, dance, plays and poems. About 20 pupils from her school dance as part of the Sunday morning Mass at St. John and Paul Catholic Church in Mathare.

Odero, a success story for the Notre Dame sisters, has her own success stories. One is 17-year-old Ian. Although his peers are in form three (11th grade), Ian is still in seventh grade, after "irregular attendance" for more than two years, she says. "The boy is a total orphan," says Odero, who was asked by Ian's neighbors to help him get back in school. "Ian had no one to take care of him but, as we speak, he is one of the best performing pupils in his class," interested in engineering and hoping to improve life in the slums, she says.

Many of her students come from families headed by children; their parents died, were killed while executing crimes or were arrested for brewing illicit beer called changaa. Some are HIV-infected, and some have no idea where their parents are, Odero says. "They need people to talk to them and give them hope for the future because, without this, they are traumatized."

Odero says the frustration and stress can be enormous for these children, many who are victims of abuse and neglect. She struggles to provide enough food and teaching materials.

She is hopes to fundraise in order get a land in Mathare to build a school and a rescue center for homeless kids. For classrooms now, she rents rooms made of sheet iron with mud floors.

Odero also wants to buy land outside Nairobi to start a farming project to grow food for her students. She also dreams of creating a vocational training center to prepare children for jobs after they finish school.

Odero meets most of her donors online and writes proposals to garner international support. "We receive volunteers who come to mentor our teachers so as to equip them with more knowledge. Some come to distribute school uniforms and learning material," she says. Volunteers from foundations stay up to six months or a year, depending on the program.

Though the School Sisters of Notre Dame left St. Theresa's more than eight years ago, they run three other schools in western Kenya in addition to outreach programs for orphans with HIV/AIDS and other vulnerable children.

Sr. Mary Odundo is a counselor in Homa Bay County in western Kenya, where HIV/AIDS has claimed many lives. She is impressed by the good work being done by the alumnae of St. Theresa's, especially Judith Odero. Odundo says the call of the School Sisters is to offer transformative education, and she is happy it has been able to bear fruit through its former students.

"Judith's initiative is a wonderful idea and a brave move. Few people would think about starting a school for vulnerable kids, much less risk working in the slums," Odundo says. She adds that Odero has both knowledge and wisdom combined with good values learned from the sisters.

"I am delighted that we were able to help [Judith] reach her full potential and that she is now giving others the opportunity to reach theirs, too," Odundo says.

[Rose Achiego is a freelancer based in Nairobi, Kenya.]