Lakshmi Kumari is a confident girl, even though she belongs to the Musahar — the lowest among the former untouchable castes in India. Unlike her mother and other older Musahar women who are illiterate, the 16-year-old girl has completed high school and learned to repair computers and cellphones. She also practices karate for self-defense.

"I am today what I am because of Sudha Didi ("older sister")," says Lakshmi, who lives in a boarding hostel for Musahar girls at Danapur, a satellite town of Patna, capital of the eastern Indian state of Bihar.

"Sudha Didi" is Sr. Sudha Varghese, a member of the Patna province of Sisters of Notre Dame, who has been working among Bihar's Musahars for the last three decades.

The 68-year-old nun, who insists she be addressed only as Sudha, says she focused on educating Musahar, especially girls, after she learned about their education level, which she called pathetic. Citing 2011 census figures for literacy, she says, "It is about 2 percent among men and less than 1 percent among women."

Manoj Menon, a journalist, hails the Catholic nun as "an angel of hope" for a people "who have lived in the dark tunnel of starvation, oppression and ignorance for centuries." An impressed Menon, who met the nun while covering elections in Bihar 12 years ago, then featured her work in his newspaper Mathrubhumi ("motherland") and followed it up with another article on Feb. 5 this year.

Menon, a Hindu, says the nun could bring drastic changes among Musahar women because she identified with them, living in a thatched hut in their hamlet, eating whatever they provided, even rat meat.

Sudha says what she did was to join the poor in their struggle "for existence, dignity, identity and livelihood." She says she plunged into it despite knowing it was going to be a long struggle and journey. "But the poor and marginalized deserved my life, love and service the most."

Serving the poor was what took her away from her home in Kerala, southern India, to Bihar in 1964 to become a missionary. After initial training with the Sisters of Notre Dame, she was sent to the congregation's schools to teach.

"Big schools and children from rich families did not satisfy my search," recalls the nun.

So, in 1977 she began visiting the poor, especially the Musahar when she was in Bhojpur district. In 1986, she moved her residence to the village of Asopur near Danapur to be closer with the Musahar. Her mode of transport was bicycle and people fondly called her "Cycle Didi" ("big sister on a bicycle").

Sudha says what she saw in the Musahar village shocked her. They lived in fear and squalor far away from other communities. They worked as agricultural laborers for landlords, who underpaid them and often sexually abused the women.

"The women believed getting raped was their destiny," she says. Most Musahar men spent their days drinking locally brewed cheap liquor. "They had no self-esteem," she recalls.

The upper castes controlled various government welfare programs and denied the Musahar access to subsidized food, primary health centers and schools. The police and government officials colluded with them.

Sudha adopted a two-pronged approach to confront the system. She educated Musahar girls and fought cases in courts for the hapless community. She was convinced that only education could improve the Musahars' plight.

Assisted by two younger nuns, she gathered women, taught them about their rights and protested injustice. She also obtained various government welfare benefits for them. To fight the legal battles, she studied law.

Her activism invited the wrath of the upper-caste people, who threatened to kill her. She told her detractors that many people would come to take up her cause, if she were killed.

However, she moved to another village in 1989, as advised by her supporters. "Many Musahar people wanted us to stay with them," she said.

Sudha brought revolutionary changes among the Musahar through Nari Gunjan ("Women's Voice"), an umbrella organization she launched in 1987 to coordinate multilayered activities such as education, advocacy and welfare services.

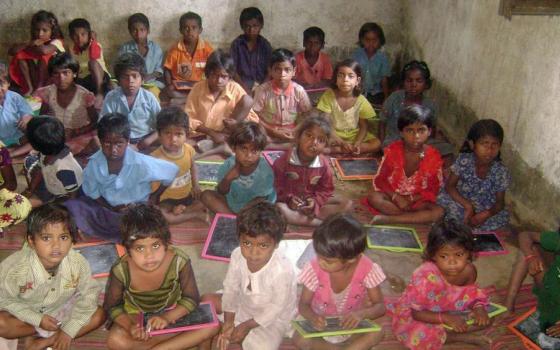

She started teaching Musahar girls in 2001. She went after the unschooled and school dropouts and taught them about reproductive health, nutrition, cleanliness, sanitation, and small savings initiatives.

Only a few girls used to attend the government schools in their village. Even those who dared to go, such as Kumkum Kumari, faced ridicule from upper-caste people. Some teachers, who were also upper caste, neglected and ridiculed them.

Kumkum told GSR that people jeered at her saying, "Look at that Musahar girl going to school." The 12-year-old dropped out and started tending grazing cattle or collecting cow dung that the Musahars dried in the sun to use as fuel.

It was then that Sudha met her and brought her to the Danapur boarding facility to stay with girls such as Lakshmi.

About 250 girls like them now reside in two hostels the nun manages — a second one at Gaya, 65 miles south of Patna. Sudha named the boarding place Prerana ("inspiration") to encourage the girls to look beyond their social deprivations.

Lakshmi says Sudha met her when her parents were planning her marriage after she dropped out of the school in third grade. "Sudha Didi persuaded my parents to send me for higher classes in the Prerana hostel," she told GSR.

Sudha opened hostels when she realized the girls could not study if they stayed in their huts. "Their emotional and mental levels are different from other children. We need to understand this first," she explains.

The nun says her efforts have produced the desired fruit. "The Musahar mothers have realized that education is the most powerful tool of empowerment. The women now take the lead to send their children to school."

She launched a program called Aksharanjal ("region of letters") to make adult women literate. More than 700 women now can read and write, and they put pressure on their community.

The Nari Gunjan also manages 40 Kishori Kendra (centers for teenage girls), each with 40 children, in various parts of Bihar. It has also set up 42 centers to offer education coaching and national test preparation to girls.

Sudha's organization has opened five centers in Purnea, about 230 miles northeast of Patna, where 70 girls pursue higher education. It also manages a computer training center at Parsa, a few miles from Patna.

All this has helped 2,250 girls to graduate from high school or skill training centers in the last 30 years, Sudha says.

The Nari Gunjan coordinates over 1,000 self-help groups for Musahar women in Patna and Saran districts. Each group teaches its members about their rights. Group members, about 10 to 15 per group, learn financial independence through savings societies.

Sudha's organization also manages two child adoption centers that care for 26 girls. In another center, her volunteers tend to about 100 elderly women. They also manage a place for women rescued from human trafficking and run a program under the government-supported Jivika ("livelihood") operation.

Rajiv Kumar, a project manager with the organization, says Sudha's work is "very challenging but rewarding." The Musahar respond positively to the initiatives. "They tended to become dependent on Sudha Didi initially. But now, they can stand on their feet," he says.

Sudha's work among the low-caste women attracted the attention of the government and others.

In 2006, the Indian government presented her with Padma Shri ("lotus honor"), the fourth highest civilian award in the country.

At a reception for her that year, the then Archbishop Benedict Osta of Patna, applauded her fight for the voiceless. "Our heads are held high by you. Our church is honored," the Jesuit prelate said.

She has been honored many times since then for her work in human rights and education, earning the Vanitha Woman of the Year award on International Women's Day in March, the Icon of Bihar Award last year, and serving on the state Minority Commission and the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights.

Sudha credits the Musahar people for these awards and accolades. Accepting the Padma Shri Award, she said, "The honor is because of the Musahar people. If they had not accepted me, I would not have been able to do what I did."

Sudha says her biggest award came when the Musahar people built a hut for her in their village. She was thrilled to hear about a 14-year-old boy resisting his parents' efforts to arrange his marriage. The legal marriage age in India is 21 for boys and 18 for girls. "This is an example of social consciousness and empowerment," Sudha claims.

The villagers have now approached her with a new request. Repeat with their boys what she has done for the girls. The boys are worried they will not find brides if the girls get educated and they remain illiterate.

"That was the turning point in my life. I found a new meaning and much satisfaction as a religious sister, in my commitment to the poorest of the poor," she says.

[Jose Kalapura is director of the Jesuit-run Xavier Institute of Social Research in Patna. An author and journalist, he specializes in Christian history and the socially disadvantaged communities of Bihar.]