In A Light to Light Other Lamps, Sr. Maureen Moorhouse recounts years of hardship and spiritual satisfaction, disappointment and rewarding relationships for the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Zimbabweans they have worked with for six decades.

It is a dispassionate tale – if you are doing God’s work, you neither complain nor marvel – brought to life by various memoirs from the sisters who live and work there.

And it is a tale threaded with the legacy of colonialism. Sisters recount everyday life in white-run Rhodesia and the transition to black majority rule that, more than 30 years on, has left Zimbabwe’s promise unfulfilled.

Founded by Nano Nagle in 1749 in Ireland at the height of the Catholic oppression, this small band of dedicated women religious spread across the world, moving to India in 1887, from where they set sail for Zimbabwe in 1949.

The Presentation story in Zimbabwe began when Bishop Aston Chichester of what is now the Harare diocese sent the first five sisters to Mount Melleray Mission in the country’s Eastern Highlands on the border with Mozambique, some 170 miles from Harare. Sr. Marie Louise Frost, the only living Presentation pioneer, says that Mother Josephine O’Connor was aghast at what they found there.

“What they told us was a convent looked like stables because there were no windows, only doors,” Frost writes. “There were two bedrooms with three beds in each room, a dining room and a kitchen. We discovered other surprises: there was only one bathtub, which we had to share with the priests. I did everyone’s laundry on Mondays in cold water from the river (there was no electricity or piped water).

“We taught in the mission – the girls lived in thatched houses of poles plastered with mud and the floors had to be spread with cow dung each Saturday to lay the dust. We had brought medicines from India and we gave them out on Sundays but there was no clinic: that lay in the future.”

Establishing new outposts and challenging racism

Next the sisters moved 49 miles north to Avila Mission, where they built a primary and secondary school and a clinic. The mission had no running water. They used water from the nearby river, which happened to be full of parasitic flatworms that enter through the skin and cause organ damage (bilharzia). St. Kilian’s, some 90 miles further on, was the third Presentation sisters’ mission.

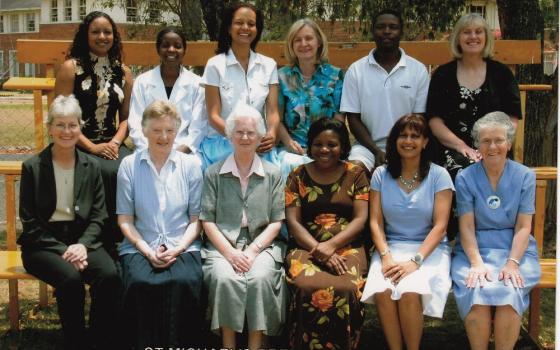

In the early ‘50s, Presentation sisters also established St. Michael’s preparatory school for St. George’s College in Salisbury, now Harare.

Presentation sisters thus found themselves working among black and white people – but the two worlds did not intersect until January 1963, when St. Michael’s accepted Solomon Chiweshe, its first black pupil. The action contravened the Land Apportionment Act, which had created zones for white and black people to live separately.

A group of parents, including two members of Parliament, demanded an explanation: they were told that because Solomon fulfilled the admission requirements, there was no reason why he should have been refused. Only one parent withdrew his son in protest.

Little more than a year later the liberation war had broken out, pitting the minority white government against black nationalists. The 16-year civil war would tear the country apart and stoke international tensions until the handover from white to black majority rule would finally be signed December 1979.

The Presentation sisters’ three missions on the Mozambique border, in the line of fire between guerrillas and Rhodesian security forces, were constantly harassed.

Bishop Donal Lamont of Manicaland, a province along the Mozambique border, was an outspoken critic of the Rhodesian regime. He told the sisters to deal without fear or favor with both sides because it was not their struggle. Moorhouse writes how the sisters used to hear the tramp of boots passing through the mission during many long nights, and they often gave the guerrillas food and medical treatment.

“So many of the guerrillas were Catholics. They were just boys and they wanted to come into the mission every evening to say the rosary with us. The bad ones had been brainwashed and did do dreadful things – but they were not the majority,” Moorhouse writes.

The sisters became so admired that at one stage a group of guerrilla commanders suggested adopting their new grey and blue habits (a modern response inspired by Vatican II) as the female guerillas’ uniform. As the war heated up, the Presentation sisters in the Eastern Highlands, among others, were forced to close these missions and relocate.

(Sisters would return to the Eastern Highlands of Zimbabwe only in 1996. This time it was to the city of Mutare, 166 miles from Harare, and they focused entirely on St. Mary’s school in Chikanga, a new township with no secondary school. )

Presentation sisters forced out of the missions on the eastern border moved to Wadzanai – “lay down the hatchet” – a training center that opened on St. Michael’s spacious grounds in 1978 and has become a college offering religious education to young men and women.

Damages of war

Not all of the sisters’ projects succeeded.

At independence in 1980, Sr. Aletha Matiswayiri, the first Presentation sister from Africa, and Sr. Madge Aherne went to reopen St. Therese Mission at Chiduku 50 miles outside Harare. They worked hard to put the hospital back into shape after the damage done during the war.

“We were so eager to resume our missionary work that we presumed too readily that peace had come,” Moorhouse writes. “The convent showed signs of the ravages of war. There were patients in the hospital, but the buildings were badly in need of repair. People were affected emotionally and psychologically by the war experience, and they also experienced a degree of uncertainty and apprehension for the future.”

Nevertheless the hospital was repaired and the workload increased. The two sisters would be up early each morning, anxious to help the sick, the wounded and, above all, the babies. The number of patients increased; the sisters attended outside clinics over a wide area three times a week, and the babies were being vaccinated and records were being kept.

“Such a peaceful routine could not continue after the upheavals of the war. There were disturbing signs on Christmas Eve when a group of men disrupted Mass – but left eventually,’’ according to Moorhouse.

The staff and the wider community did not accept the sisters’ presence, and on the evening of Christmas a gang of people came to attack them. “We saved ourselves by locking ourselves in but left early the next morning . . . We returned to Chiduku on January 7, and when the same thing happened again the mission was closed,” Sr. Margaret Ahern is quoted as saying.

Moving forward

A happier fate awaited a girl’s school, Nagle House, which opened in Marondellas (Marondera) 55 miles from Harare in April 1959. From its early days public exam results showed good passes at this small school in a wide range of subjects and topics, such as mathematics, English, science, French, art and biology.

By the 1970s the sisters felt the need for closer contact with people nearby in the poorer township of Dombotombo and, despite the restrictions on interaction between whites and blacks, Moorhouse would cycle there from Nagle House to teach English and help them pass their English exams.

Today Nagle House is one of only four post-independence stations that the Presentation sisters run. The others are St. Michael’s school in Harare, St. Mary’s secondary school in Chikanga in the Eastern Highlands and the Guruve outreach program.

Guruve, 100 miles from Harare, survives despite initial problems with the parish priest, who felt the sisters were there to cater to his every need, not those of the community.

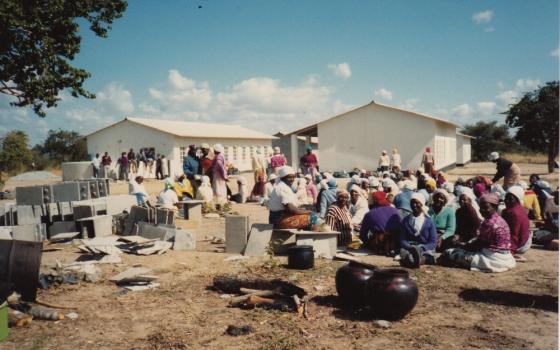

In 1989 Sr. Nora Broderick, Sr. Eileen Clear and candidate Judith Bingura took up residence in a newly constructed cook’s house and began preparing children and adults for the sacraments at the mission and its 12 outstations.

“We are a diminished congregation. It is hard to attract the right sort of young women – so many are focused on material things,” Moorhouse told GSR. “At first we accepted anyone and this was a mistake: several of the girls did not understand religious life and found they couldn’t cope.”

A new novice joined the order this year, a cause for celebration. She is in Guruve and, if she decides to take vows, the Presentation sisters will send her to their congregation in the Philippines for two years, after which they will encourage her to take a degree, probably with a view toward becoming a teacher.

“Anatola joined us from Chihota two years ago: she says she remembers me from when she was three and decided then that she too wanted to be a sister. I suppose it was because I’m white. She is a delightful girl and we are proud to have her join us. I do look forward to her return from the Philippines.” Moorhouse writes.

As their congregation in Zimbabwe became smaller it joined together with 40 Presentation sisters in Zambia where Sr. Bella Vethemuthu, originally from Tamil Madui in India, is the superior general.

Despite the smaller presence in Zimbabwe the community of Presentation, Moorhouse writes that the sisters continue to live up to founder Nano Nagle’s message:

In the face of fear . . . chose to be daring

In the face of anxiety . . . chose to trust

In the face of impossibility . . . chose to begin.

[Jill Day is a GSR contributing editor and writer in Harare.]