Chaldean religious find peace and hope in Chicago

There is nothing on the outside to suggest the brick two-story house is unlike any of the thousands of others that surround it on the north side of Chicago, until Sr. Margaret appears at the door.

She is slight, and her flawless white tunic matches the brilliant white band on her black habit. Her dark eyes sparkle brightly as a cloud of incense from morning prayers billows out when she opens the door.

This anonymous house, near a Jewish school, is the convent of the Chaldean Daughters of Mary Immaculate Conception, and Sr. Margaret Homa is one of the two sisters living here, having recently moved after 16 years in San Diego.

It’s a beautiful fall day, and as she leads me into the living room, I ask her if she’s prepared for the brutal Chicago winter to come.

“Oh yes,” she smiles. “I look forward to having different seasons again.”

Despite her time in southern California, seasons – and bitter winters – are nothing new to Homa, as she grew up in northern Iraq, where the terrain turns mountainous and winters are cold and sometimes snowy. Her family lived in Shaqlawa, in the mountains about 80 miles east of Mosul.

In fact, Homa, ethnic Chaldeans and the Chaldean Catholic Church are well acquainted with difficult environments of all kinds: Established in what was originally Mesopotamia, the Chaldeans have a history filled with invasions, persecutions, massacres and genocides. Now, after decades of persecution by Islamic governments in Iraq, Chaldean Christians are being taxed, kidnapped and slaughtered by Islamic State terrorists.

The church dates back to apostolic times and is part of the Eastern Rite under the Chaldean Patriarch of Babylon; it is in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church – the pope appoints Chaldean bishops – resulting in rich, orthodox liturgies that are nonetheless familiar to any Roman Catholic.

There are 12 Chaldean parishes in the United States, including two in Chicago, where there are an estimated 7,000 Chaldean Christians. The church encompasses believers from Iraq, Iran, Syria and Jordan, so Masses are often in the common language of Arabic, but ethnic Chaldeans speak a language Americans would identify as Aramaic, known as Jesus’ native language.

Homa offers me tea, then sits on a couch beneath a row of portraits of Chaldean patriarchs. On top is a portrait of Pope Francis. She explains that she was very happy in San Diego, but the bishop decided he would rather have diocesan sisters, under his direct control, instead of the Daughters of Mary.

“We were hand in hand with the church,” Homa says. “So it was kind of a shock. You get the feeling that you don’t belong to a church, which is especially hard when you’ve dedicated your life to the church.”

She never feels unneeded or unwanted in Chicago: The only other sister here is 84 years old and bedridden, and Homa is kept busy between the St. Ephrem parish just a few miles away and the Mart Mariam parish about a half-hour north in Northbrook. There are catechism classes, youth meetings at both churches, a choir to coordinate and a women’s group. Not to mention daily Mass, prayers, vespers (which they call ramsha), and rosaries to pray.

“It’s very overwhelming – there’s a lot of work here to do,” Homa says. “But God prepared me all these years.”

She begins to tell me about the tight-knit Chaldean community when her smartphone rings.

“Good morning, Father!” she begins in English, then switches to what I assume is Chaldean Neo-Aramaic. While she talks on the phone, I wander around the first floor, looking at the portraits in the entryway of St. John Paul II and St. John XXIII, a painting of Jesus that has had gold adornments applied to it like a crown, and the former front sitting room turned chapel, where the air is still heavy with incense. Near the landline phone is a laptop computer and a copy of “Spiritual Advice From the Saints.”

Off the phone, Homa tells me that despite how busy she is, she recently enrolled in online theology classes. It’s a lot to take on, but it’s also part of a commitment she made to her late father when she entered the convent at age 16.

“I wasn’t really mature enough to know what I was doing,” she says. “But my dad said, ‘I will allow it if you’re willing to accept the challenges, but promise me you’ll never stop going to school.’ I said, ‘No problem.’”

‘Fear grew up with us’

Homa, like most Chaldeans, grew up in two worlds; no matter which one she was in at the time, the other was never far away. At home, the family spoke Chaldean and was very strict in their faith, praying the rosary every night and going to church almost every day. But outside the house, she was a Christian in a Muslim world: Until fifth grade, school was in the Kurdish language, and most of the children she knew practiced Islam.

“We were very scared even to sit outside, so people wouldn’t see us. We learned not to show yourself to people,” Homa says. “If you acted in a certain way, it might put you in danger. If a boy approached me and wanted to talk to me, I ran away.”

The Iraqi culture taught that Christians were to be despised.

“Boys would try to kidnap girls and hurt them,” she says. “Fear grew up with us.”

Still, there was no escape from the Muslim world: Her parents owned a kind of small grocery store where the children would help out, and outside the home, they had to speak Arabic.

“You’re forced to live in that situation,” she says. “You were taught that no matter what, they are Muslim, and you can’t give them trust.”

And, whether that attitude was right or wrong, she says, it was constantly reinforced by both sides.

“They don’t respect the things you do, but you have to respect them,” she recalls.

She gets up and begins preparing lunch, explaining that we’ll be joined by Fr. Fawaz Kako, pastor of Mart Mariam. As she cooks, I ask her what it’s like to live in the United States after it waged war against her homeland not once, but twice during her lifetime.

But who attacks whom doesn’t matter to her: War is war, and all that matters is that it stops. She was 12 when the Iran-Iraq War began in 1980; she was a novitiate in Baghdad when Iranian missiles began falling on the city and the sisters had to flee to an outpost north of Mosul where it was safer. That brutal war – half a million soldiers died and a similar number of civilians – lasted eight years.

“I can’t judge. For me, it’s the leaders who are to blame,” she says. “My oldest brother was in the army. I prayed every day to St. Rita to bring him back safely.”

Homa was 23 and studying in Italy when the Gulf War took place.

“It was my first time out of Iraq, and there was no communication – no phones, no letters, nothing,” she says. “And what you hear from the news just makes it worse.”

She later found out a cousin was killed.

Homa was in San Diego when the Iraq war began. I want to ask her what it was like to be an Iraqi in the United States during that time, but I’m interrupted by the arrival of Fr. Kako. He sits down to talk while Homa finishes cooking.

He explains that Chaldeans in the United States are also in two worlds: Mart Mariam now has a Saturday Mass in English to cater to children.

“They’re first-generation Americans,” he says.

The 10 a.m. Mass is in Arabic and the 11:30 Mass is in the Chaldean's language. This, too, is part of their duality: Arabic for ethnic Chaldeans is the language of the oppressor. But it’s also the native language for the Syrians, Jordanians and Iranians who are Chaldean Catholics, and a common language for everyone. The sign of their differences also unites them.

They live in the United States, and love their adopted country and its freedoms. But they’re also a very close family, united in exile, Kako says, trying to maintain their unique identity.

“This is our promised land, where we can prosper,” he says.

‘Still on the cross’

Kako, 33, grew up in Baghdad, and was sent by the Redemptorists to Germany, then to Chicago. Despite the horror and persecution happening in Iraq, he remains inspired by those who have gone before.

“Back home, the church was a society in the middle of a society. Our ancestors were converted to Islam under the sword,” he says. “Our community has been persecuted from the first century; how we survived is only through the will of God. But we’ve kept our traditions, we’ve kept our language and, of course, we’ve kept the faith of Christ in our hearts.”

As I am speaking to Kako, it’s clear he has worked hard to develop an American accent over the nine years he has been here. He was ordained a Chaldean Catholic priest in 2010 and became pastor at Mart Mariam in 2011.

If there’s one thing that galls him about the United States, it’s that people don’t appreciate the freedom to worship as they wish.

“For us, it’s, ‘Hey, I didn’t see you in church.’ We still say that in our community, but being from a crucified church, you have to,” Kako says. “We had two dioceses [in Iraq] that just disappeared from the face of the Earth in one day because of ISIS. These were dioceses built in the first century.”

How dire is the situation?

“Iraq is not a safe place for Christians anymore. There are only three options: Be killed, convert to Islam or pay taxes. Christianity is still on the cross in Iraq, and we’re waiting for that third day.”

The taxes Kako refers to are known as Jizya, or tribute, imposed on Christians and Jews, that can be as high as U.S. $400 per person per month.

“Our hope is in Christ. That’s all there is,” he says. “And our patriarch is in Iraq right now. He’s very courageous; he’s not leaving. He says, ‘I’m with you all the time.’ That’s a sign of hope.”

But how do you find hope amid the slaughter, when even children are being beheaded? The Daily Mail reported recently that Iraq was home to 1.5 million Christians before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. There are now only about 250,000, most of whom have had to flee from their homes. Yazidi leaders told Vatican officials Jan. 8 that an estimated 5,000 Yazidi women are being held as slaves by ISIS militants.

Where is God in all of this?

“You gotta believe him, even though sometimes you say, ‘Seriously, how is this going to happen?’” Kako says. “But we always believe that gold is tested by fire.”

Homa comes in to tell us lunch is ready, and at a table laden with food for just three people, our talk turns to food, calories and trying to stay in shape, especially when Homa shows Kako a platter of something similar to a pasty – a crust filled with mashed potatoes and meat. A friend sent these pies frozen from Detroit, and despite Kako’s diet, he digs in.

“I’m going to have to work out twice as long to make up for this,” he says, laughing. “But it’s worth it. I would almost drive to Detroit myself to get these.”

All of the food is delicious, and as a reporter, I know I should ask what things are, but I’m too busy stuffing my mouth to do so.

‘I was crying all the time’

After lunch, the talk again turns to the situation in Iraq, and how hopeless it seems.

“One of my best images is of Jesus sitting on the donkey,” Kako says. “Most of the time I feel like I’m that donkey.”

The donkey didn’t know it was carrying the savior of mankind to his glory, didn’t understand its place in history – it only knew it had a burden to carry.

“Sometimes we all feel like that. We say, ‘God, save us,’ but his saving plans are beyond this world, beyond any government, any laws. Look at the Dark Ages – that was a time when we had great saints. God takes the fool, the oppressed, and makes them an example for others.”

Kako hasn’t been back to Iraq, but Homa goes back every three years to see her family. Her parents have both since died.

Her last visit began May 31; just a few weeks later ISIS attacked. Her hometown, Shaqlawa, is one of the places Christians fled ahead of the militants, and Homa immediately helped care for the approximately 500 families who had become refugees.

“One of the girls said, ‘I don’t want to pray anymore. Why would God allow this to happen?’” she says. “Others said, ‘It’s not fair. What did we do? Why is this happening?’”

The people had been forced to leave everything behind and were now living in a Shaqlawa banquet hall. They were forced out of their homes with no money, no cars, no passports.

“At first, I was confused, I didn’t know what to do, so I just started to pray with them, and soon I could see joy in their faces,” Homa says. “In the beginning, I couldn’t help myself, and I was crying all the time. At the end I was stronger.”

There were two other sisters there, as well, and the three worked morning to night.

“I gave a man a rosary, and he began to cry,” Homa says. “He said, ‘Do you know how many rosaries I left behind in my house? And now I am begging for one.’”

But, as so often happens, those who help those in need find themselves receiving as much or more than they gave.

“I see myself as very lucky to be with them at that time,” she says. “They were very comforted and at peace when they see the religious around them. The [banquet] hall didn’t have showers, so people would take them to their homes to bathe. It was a good opportunity for everyone to show unity.”

Among survivors, those in Shaqlawa were luckier than some. In Ankawa, she says, there was no place for refugees to stay, and they had to live in tents or on the streets. But they were also alive.

“As a human being – not just as a faithful person – as a human being, this is not acceptable,” Homa says. “These [militants] have lost all sense of being human.”

Dead bodies in the street

There is another fear, both tell me: What war does to the children who survive.

“Their whole childhood, they grew up hearing bombs and planes,” Kako says.

It’s a fear Homa’s family feels, too.

“My brother says, ‘We don’t worry about us, we worry about our children. They grew up with war and all these fights – how are they going to live?’” she says. “It’s very hard to find solutions.”

It’s a fear they both understand because they also grew up knowing little other than war. The first eight years of Kako’s life encompassed the Iran-Iraq War; he was 10 during the Gulf War.

“There was talk that Baghdad would be attacked with chemical weapons, so we fled north with thousands of others,” he says. “We were 35 people in a household built for five.”

And even there, war found them.

“I remember a plane came, and I remember holding a rosary in my hand under the table and saying, ‘Why is this happening to us?’” Kako says. “But in every tragedy, you have two options: You can take it to heart and let it mess you up, or you can work against it, and in the midst of war and pain and suffering, let God use you as an instrument of peace.”

The only real choice, he says, is peace.

“I’ve seen dead bodies in the street. I’ve dealt with people that treat you as a second-class citizen. But instead of hating, you pray,” Kako says. “That wasn’t only me or Sister, that was the whole community, because of Christ. We are who we are today because of our love for Christ. In the midst of our chaos, he creates order.”

Even when there wasn’t war, there were embargoes and hardships. Kako never tasted chocolate as a child, and after 1990 all the cartoons on television were about killing and war.

“There were two channels, and both were Saddam Hussein all the time,” he says.

When Homa joined the convent and went to Baghdad, she was not allowed to wear a habit; Kako knows all the verses of the Koran because he was forced to sit through Islamic classes in public schools.

That choice – between war and peace – seems to never go away.

“All my life, we had war, war, war,” Homa says, her voice getting smaller as the Chicago sun begins to set and the shadows in the room get longer. “Where is the peace? Sunni and Shiite – we are always in the middle.”

“You’re always in the middle and you’re always the infidel,” Kako continues for her. “And in a country that, historically, belongs to you.”

There is silence for a moment, and then it is time for prayers at St. Ephrem.

Between two worlds

St. Ephrem Chaldean Catholic Church, Fr. Sanharib Youkhana tells me, was the first Chaldean Catholic parish in the United States, established in 1904. The current building was constructed in 1962 for 55 parishioners; the church now has 350 and continues to grow.

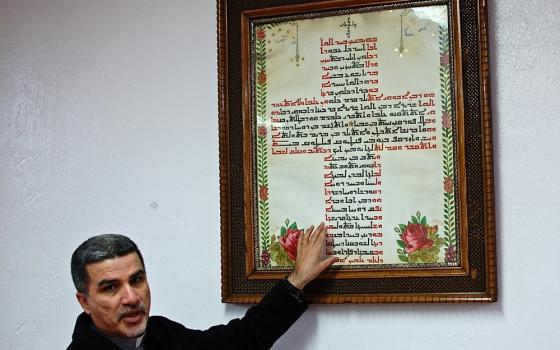

His English is not as clear as Homa’s and Kako’s, but there’s no misunderstanding both his pride in the parish and his warm welcome. From the darkened sanctuary, where about two dozen people are praying out loud, their voices rising and falling in a call-and-response, he practically drags me around the church to show off its history, its artwork and his office.

I tell him I want to take a few photos of people praying if it won’t be an intrusion, so he takes me to the side entrance to the altar and says I can shoot from there. I step through the door with my camera, only to be confronted with the fact that two dozen Middle Easterners are staring at the white guy in business casual with a huge camera taking photos of their faces as they kneel. I immediately turn back.

“No, no, it’s O.K.,” Youkhana insists.

I go back and take a few photos, but only after he promises to tell them I’m a reporter, not some government agent.

“It’s good,” he says. “You take pictures.”

Back in his office, though we’ve only known each other for a few minutes, he insists on giving me a gift: A lovingly worn Chaldean-Arabic dictionary. With the voices still rising and falling in prayer coming from the sanctuary, I realize that since I do not speak or read neither Chaldean nor Arabic, it will be one of the most useless – and treasured – gifts I’ve ever received.

I think about that dichotomy again as I step from the darkened church out into the fading light of bustling Chicago, moving from one world to another. And something Kako said earlier comes back to me about living in two worlds.

“We are split in half,” he said. “We are American citizens with rights and responsibilities. But another part of us is back home with our people.”

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. Follow him on Twitter @DanStockman and on Facebook.]