On a mild day in December, I found myself at Springbank Retreat in Kingstree, S.C. – sitting in a tipi. I’d never expected to usher in the new year at a Native American pipe ceremony, but I was moved, and honored, to participate.

I’d been looking for a spiritual place to get away for a few days after Christmas and write. I found Springbank on the Internet and wrote to director Sr. Trina McCormick, who told me to come on down.

Past country fields and dilapidated barns, I drove the two hours to Kingstree from where I live, Charlotte, N.C., until I finally parked in front of Springbank’s stately white main house. I was met by a woman in a plaid shirt, Jerilyn Skyface Flowers, a photographer and caretaker of a farm in Georgia. She was staying at Springbank for two months to build a tipi for the center.

The tipi Flowers eventually constructed is now a permanent fixture on the grounds, called the St. Kateri Chapel.

Later, I learned that Flowers and McCormick are part Micmac.

On my last day, they invited me to participate in the pipe ceremony. Five of us sat in a circle on the floor of Flowers’ own tipi, and offered prayers as we puffed smoke from handmade pipes in the seven directions: north, east, south, west; and above, below, within. McCormick led the ceremony. The whole experience felt sacred to me. Even sacramental.

“The presence is in every direction – above, below, within – and if we really knew that, how differently we’d live our lives.” McCormick said to me later. “But we forget.”

Blazing a trail

“Healing Self, Healing Earth.” That’s Springbank’s motto.

A post on National Catholic Reporter’s EcoCatholic blog earlier this year shared details from an Atlantic magazine story, “Nuns with a New Creed: Environmentalism,” that profiles religious communities in the United States and Ireland dedicated to teaching people about conservation, clean energy, and respect for the natural world.

Springbank Retreat Center for EcoSpirituality and the Arts is part of this mission.

It hosts sabbaticals each spring and fall. While they’re open to anyone, most of the sabbatical participants are women religious. Laypeople of all faiths are welcome, too, and often come to the grounds for personal retreats.

Springbank is in the Diocese of Charleston – the only diocese in South Carolina, a state that’s around 3 percent Catholic, McCormick said. The center has had a presence by the Dominican Sisters of Adrian, Mich., since the 1980s, when Sr. Betty Condon became the center’s director for 17 years.

When she first arrived at Springbank to help Condon in 1986, “There were no trails, and the property was still very overgrown with vines,” McCormick told me. “Everything was in need of major care. My first thought when I saw it was, ‘Oh, this is too much work. I’ve got to get out of here.’”

McCormick, 68, has a strong background in the visual and healing arts. She grew up in Miami, one of 11 children, and entered the Adrian Dominican community after two years of college, eventually earning an MFA in painting from Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles. She also attended San Diego School of Massage and later studied with Henri Nouwen. She came to Springbank with Sr. Ursula Ording, who became the center’s director. The two Adrian Dominicans had conducted retreat work together in Massachusetts. Ording, who taught pottery at the center, died in 2013 at age 78.

After her California studies, McCormick said, she and Ording considered their ministry: “Our original dream [was] to be at a beautiful place where we could invite men and women to come and to discover their creativity, through quiet, through being in the natural world.”

“I love it here,” McCormick says now.

History

The first house on the land was built in 1782. Original owner John Burgess developed his 5,000-acre plot into a rice and cotton plantation. A slave cemetery for the hundreds who worked the land still stands in the woods, marked with crosses; the 1989 devastation of Hurricane Hugo destroyed many earlier grave markers, and new graves are still being found.

The home’s last owners, Howard and Agnes Hadden, acquired it in 1930. Howard gave it to his wife as a wedding gift. The current house was rebuilt along the original plan after a fire in 1947. Agnes Hadden was friends with Clare Booth Luce, who had given her property to the Cistercians to build Mepkin Abbey in South Carolina. Booth Luce encouraged Hadden to do the same, so in 1955 she gave her property to the Dominican Order of Men to be used for spiritual purposes. In the 1960s, Dominican priests operated Springbank as an outreach center. The center closed in 1979. For a few years, it stood abandoned. Then, in the early 1980s, sisters and priests returned to clean it up and reposition it as a retreat center.

Springbank was turned over to an ecumenical board of directors and has been staffed by sisters since. The core staff – McCormick; Sr. Theresa Linehan, 66, of the California province of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur; and Margaret Welch, the cook, live full-time on the grounds.

McCormick, Ording and Franciscan Sr. Karla Barker, a member of Springbank’s staff for 21 years, together created the sabbatical program. (Barker died on September 17.) A number of Franciscan sisters are among the sabbatical program’s many presenters. So is Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Barbara Fiand, author and retreat leader on contemporary religious life and spirituality. She’s leading a retreat this fall.

Today, the main house holds administrative offices and a small library full of books on Catholic and Native American spirituality, women’s studies, ecology and more. Attached to the house is a chapel built of cypress by the Dominican priests. Sabbatical participants sleep in the “Large Retreat House,” a converted horse stable on the grounds.

The Cosmic Walk

On my second visit to Springbank this May, Linehan drove me around the 80-acre grounds on a golf cart to give me a tour, something she often does for visitors.

“Everything that you see in the woods has all been blazed and trailed by Trina, Karla and Ursula,” she said.

As we rode, Linehan explained sites I had seen on my own as I walked around the grounds that winter: the labyrinth; the Grandmother Tree, an enormous live oak in the front yard that is between 800 and 1,200 years old, under which the Haddens are buried; the “Circle of Trees,” a spot in the woods where author Sue Monk Kidd wrote The Dance of the Dissonant Daughter. Near the grotto, Linehan indicated a lane of bricks “made here on the property by the slaves. We think they had to make maybe 1,000 bricks a day.”

She also noted devastation still left over from an ice storm that hit the South in February: limbs down, a tree had crushed an outdoor chapel. (It was repaired in June by Sr. Karla Barker's nephews, who had originally built it.) During the storm, the sisters on sabbatical had to sleep in the living room: “That was the only heat we had, was the fireplace, and that group really bonded, really quickly.”

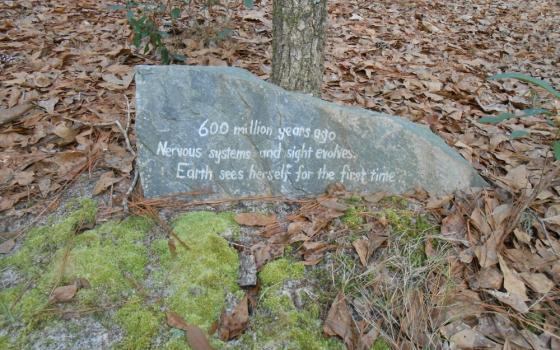

And then there was the Cosmic Walk, a 1.7-mile trail that winds throughout the woods and ends by the swamp. It’s marked by stones placed at intervals along the path with significant events lettered upon them, from “13.7 billion years ago, the universe flares forth out of ultimate mystery” to “4.5 billion years ago, birth of our sun and solar system” to the arrival of plants, insects, animals, human arts, music and various forms of religious life – all the way to the creation of the Internet in the 1990s. The wording and ideas were adapted by McCormick from the work of Sr. Miriam MacGillis, a member of the Dominican sisters of Caldwell, New Jersey, and director of Genesis Farm, a spiritual and ecological center in New Jersey.

On our tour around the grounds, our golf cart was often chased by one of the numerous dogs that live at Springbank. Sometimes they even jumped on the cart to be petted. The dogs have all been rescued – left on the side of the road, abandoned in parking lots or found wandering the woods, Linehan said.

“Because our philosophy is that we’re all related and interconnected,” she said, “we keep them.”

Sabbaticals and healing

Springbank offers sabbatical programs of one, two or three months long. Usually there are six to eight participants, Linehan said. Sisters come from all over the United States, from Maine to California. The program includes a contemplative retreat; classes in the arts, Native crafts, ecology and spirituality; and opportunities for spiritual direction, massage and healing touch (McCormick is a certified massage therapist and Reiki master).

Linehan teaches the Native American drum-making class. She is part of the “Stockbridge Muncie band of the Mohicans. I’m a card-carrying member of the tribe.”

In large and small ways, the sisters of Springbank teach care for creation. Sabbatical participants learn about the works of environmental scholars and theologians Thomas Berry, Brian Swimme, Richard Rohr and others. On the Springbank website is a quote from Pope Benedict XVI: “If you want to cultivate peace, protect creation.”

McCormick talks about Pope Francis and his calls to stop the destruction of the environment. At dinner, which sabbatical participants eat together in the main house, each person chooses a unique napkin ring from a basket and uses it to identify their cloth napkin throughout their stay, saving water and paper. They try to eat organic meals, growing food in the vegetable gardens outside. They teach about composting and recycling.

The sisters who come to Springbank on sabbatical are usually ending leadership positions with their congregations or years of ministry in a particular area.

“When they come, they tap into their creativity,” Linehan said. “Because they don’t take the time to ever do anything like that, they don’t know” how much they actually have within them.

A California native, Linehan came on sabbatical at Springbank herself in 2009 after five years in leadership for the California province of the School Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. Before that, she had ministered as an elementary school teacher and administrator and worked as a diabetes nurse practitioner with the Hispanic population in Salinas, Calif.

Linehan first heard about Springbank from another sister in her order, Judy Markiewicz of the Boston province, who had taken a sabbatical there and had been on the staff. They met at an annual meeting for their congregation, which “used to have eight provinces” in the United States. (“We had been talking about merger as every other order has been talking about,” she said.) At the meeting, she met Markiewicz “mainly because she was Native American. There’s not very many Native Americans in the order.”

Linehan sought out Springbank and had such a “wonderful sabbatical” there that she joined the board and then the staff. “I came [on staff] in the fall of 2011. And literally jumped on a plane, jumped off the plane, and then next day I was picking up people for the sabbatical program. And I don’t think I’ve stopped since.”

Laypeople also come to Springbank for sabbaticals and retreats, including ministers of various faiths who sometimes bring their church groups. Groups of artists sometimes come as well, or individuals seeking a quiet place.

It costs nothing to walk around the grounds. Short retreats based on programs range from $200 to $800 depending on length and materials. Private unstructured retreats, like mine, cost $65 a night, not including meals. (You can cook your own food in a kitchenette or join sabbatical participants at their evening meal for $10-$12). Springbank’s sabbatical programs of one, two or three months, range from $2,500-$6,500.

Bishop Robert Eric Guglielmone of the Charleston diocese is “very supportive and very caring” about Springbank Retreat and shares a respect for Native American culture, McCormick said. At the end of the spring sabbatical in April, he came to Springbank with Abbot Stan Gumula of Mepkin Abbey in Moncks Corner, S.C., and Msgr. Chet Moczydlowski from John the Divine Catholic Church in Charleston to bless the finished St. Kateri tipi chapel.

The three blessed the icons that the sabbatical participants had made, blessed the tipi, and then “the three of them went in there, and the abbot sat down, and he loved the space. Because of its . . . conical shape, it just invites you to a spiritual uplifting,” McCormick said. “Everybody who goes in, your eyes go up.”

One body

Pat Marrin, editor of Celebration, NCR’s monthly worship resource magazine, was one of the Dominicans who returned to Springbank to help clean it up for its regrowth as a retreat center following the period when it lay dormant.

In an assessment report for the order in 1981, Marrin wrote, “If certain times, places and moods can dispose a person to natural contemplation, then Springbank combines a high number of such factors in a unique way. . . . Its character seems honed and marked, and even wounded, by more than just natural forces.”

In a recent email, he expanded on the idea:

“We emphasized to retreatants that it was holy ground, but there was paradox in that,” Marrin wrote. “We were told that the site had originally been an Indian burial ground, then a plantation. It was a deeply wounded place. . . . spiritual purpose was layered on top of a history of suffering, and perhaps this helped Springbank be a place where people got in touch with reality, invited them to participate in some kind of redemptive offering there.”

And just being there did make me mindful. While walking by the swamp, I’d noticed tiny black frogs the size of bugs fleeing from my every step, and treaded carefully to avoid crushing them. At dinner one day, I told McCormick that I’d instinctively swatted and killed a mosquito outside. “I’m sorry. I wasn’t thinking,” I apologized, feeling guilty about killing another creature.

“Maybe that’s what this place is about, is helping to . . . make us aware,” she said, thoughtfully. “We’re so connected. Everything is. It’s like one body.”

[Erin Ryan is a columnist and associate editor for Celebration and a former staff writer for NCR. She was a member of Mount St. Scholastica Benedictine Monastery in Atchison, Kan., for nearly seven years. She lives in Charlotte, N.C., where she has been a freelancer for the Faith section of the Charlotte Observer and works as an assistant at Charlotte Fine Art Gallery.]