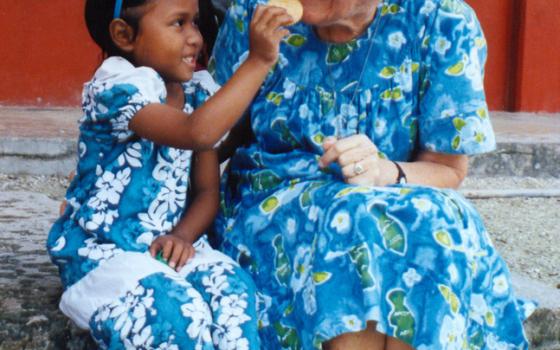

Sr. Dora Nuetzi joined the Maryknoll Sisters in 1954. She taught in New York City and Hawaii until 1985, when she moved to the Marshall Islands and taught religious education for over 20 years. Nuetzi currently lives at the Maryknoll Sisters Center in Ossining, New York, where she is working on a book detailing the history of the Maryknoll Sisters' work in the Marshall Islands. Brett Davis met with Nuetzi at the Maryknoll Sisters Center to talk to her about her experiences in the Marshall Islands for Brett's oral history book project about Catholic women religious.

______

In 1985, I flew to the Marshall Islands, and when I got off the plane, I wanted to kiss the ground. I was so happy!

The time I spent in the Marshall Islands is golden for me. It's all a gift. All a gift. There was no school there for learning the language. You just lived with a family or learned it by talking with the people.

We had two sisters who were going atoll-hopping. They were starting schools and also teaching prayer leaders. We had one priest who had been going to the outer atolls and one priest on the main atoll of Majuro. As our sisters traveled, I went with the two of them for a year. I had learned the language to a certain extent, but felt I wanted another year. I asked the pastor if I could spend another year just moving around, and I received his OK.

In the meantime, I was also learning what the needs were of the people. The atoll Likiep had been very Catholic because the Portuguese and Germans came over there. It was a very Catholic community and well-developed. I promised them I would come back and do something with them. After two years, I worked it out and talked with the community. They wanted a religion program, and I developed a program for them. At Christmas time, I took off a month from Majuro and trained the women to teach.

In Majuro, they needed a religion program and a teacher for the high school. I developed a religion curriculum, and I was delighted with what I had done there. I did teacher training and the religion program went well.

When I got off the plane in Likiep, the people were all there, standing and waving. We didn't have a real house. The convent had broken down. So we went to Father's house, and the women came and asked when we were starting. I told them to give me a day or two.

In Likiep there was electricity or anything. I had thin tissue paper with carbon in it. I had six carbons, and if you pressed hard enough, you could go all the way through. So I just wrote everything by hand and gave one paper to the teachers and began a program for religious education. And it's still going to this day, which is delightful!

Then, later, we got a manual typewriter. We typed up the lesson plans, and then eventually, many years later in Majuro, we had electricity and we got a computer. I trained the teachers, and it was fun because at night we'd have to use kerosene lamps since there was no electricity. My place was the only place lit up. The women would gather around and you'd look up and there'd be all the other people peeking in the door and windows to see what we were doing.

That was such a free and creative experience. The whole thing was free because there was no past history of how things would be done. You're creating it as you go along, and I had to work pretty fast to write and develop lesson plans. I also discovered that a lot of them had not finished high school. They had finished maybe grade school. I had a woman who was one of my teachers, but she really couldn't read. So we worked as a team and her friends helped her out to read.

Basically, I just taught right from the Bible. The first thing I did was a Christmas program. I took everything from Luke's Gospel and just typed it up. One of the blessings in the islands is that the Bible was translated around the 1970s, and it was a collaborative work between the churches.

Majuro had other churches. The Catholics came; Fr. [Leonard] Hacker came in 1948, and he started a school around 1952. The Congregationalist Church came, and they were well-established. They were there before us. Catholics were pushed out back in the early 1900s. The few Sacred Heart priests that came couldn't make any converts. People didn't appreciate them, so they just left. Father Hacker said it took him two years before they would welcome him and recognize him. Sometimes if he was walking down the street, they would just turn their heads and not look at him. He had a lot of prejudice against him, but he worked for the people and was there to help with their needs. He started a school under a tree. He had a lot of older men who were just beginning to read and write. So he did a lot in that way.

But my work on the outer atolls was a delight. In the beginning, I just had to write the program and figure out what was apropos for people there. I tried to make it as much in their culture as possible. I had another lady translate, and then we would write it up.

I got to the Marshall Islands in 1985. A small plane was purchased before I got there, and it would go from atoll to atoll, but only if there was a strip of land that was free of weeds. The strips weren't really paved or anything. If the plane was free and there was enough space for it to come down —

I would send out lesson plans on the plane and keep one step ahead of the teachers. Father and the sisters also began to have workshops in Majuro. All the outer-island teachers for religion would come during the summer for a two-week program. Sometimes, there were 100 people there because they'd come from all different places. We tried to get programs going in each atoll.

Likiep was one of my favorite places because it was the first place I went, and the people were very eager. I didn't go to all of the atolls. I went to five or six and started a religion program. They really need somebody there to get them started. I spent 17 years in the Marshall Islands. Those years were the best years! I enjoyed every minute of it!

[Brett Davis is a Brooklyn, New York-based photographer and writer. He is currently working on an oral history book project about Catholic women religious communities.]