Earlier this year, the United States reached a record $1.5 trillion in student loan debt. Almost 40 percent of the nation's adults under the age of 30 have student debt — some of them six figures' worth, the Pew Research Center reports.

The effects are far-reaching and well-documented: Because of their debt load, today's young adults are delaying or foregoing major life decisions like buying a house, having children or pursuing a religious vocation. For years, organizations have existed to help young Catholics with the latter, but with no solution to the debt crisis on the horizon — as college costs continue to increase, so does the amount of debt students take on — these groups are now looking for new ways to meet the ever-growing need.

The Labouré Society, for example, is in the process of developing a program that turns the society's original debt-elimination model on its head. Now, in addition to helping individuals fundraise to pay down their debts before entering religious life or the priesthood, Labouré wants to teach religious institutions how to raise funds to eliminate the debt they've already taken on using the same fundraising tools it's been teaching to individuals.

"I know of one institution where they're paying a half a million a year to pay off the past student loan debt for their people," said John Flanagan, Labouré's executive director. "Wow. What could you do in your mission if you didn't have to spend that half a million paying off the student loan debt that you allowed your candidates to enter with?"

Flanagan, a former missionary whose mother was a Franciscan sister for seven years, said he never gets tired of seeing people's eyes get big when they start imagining what they could do with those freed-up funds.

"That's what I'm offering," he said. "That's what we can help with."

A few generations ago, this problem was practically unheard of; the majority of would-be religious began pursuing their vocations immediately after graduating from high school and were then educated at the colleges and universities affiliated with their communities.

Today, however, men and women enter religious life after they've already earned advanced degrees and accumulated the corresponding debt. Added to that, said Fr. Stephen DeLacy, director of vocations for the Philadelphia Archdiocese, is the fact that higher education now "operates as business," often encouraging students to take on more debt than they'll be able to manage with their chosen careers or vocations.

DeLacy said he hopes the Philadelphia Archdiocese will be one of the first institutions to take part in Labouré's new program once it gets off the ground. He said he imagines Philadelphia's St. Charles Borromeo Seminary could use the financial freedom such a program would offer to support underfunded ministries and to bolster the seminary's existing donations campaign.

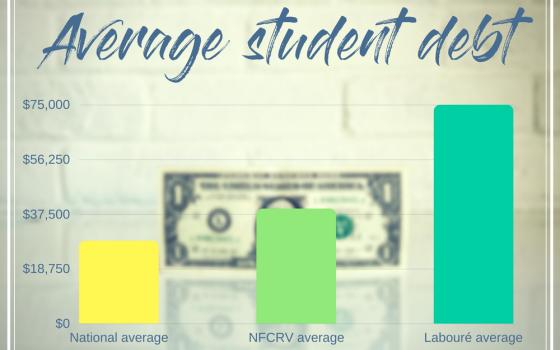

At the National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations, which awards grants to women and men planning to enter religious life, executive director Phil Loftus said he's been keeping tabs on a hot new trend in the corporate world: student-debt assistance as an employee benefit. (The fund is financed in part by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, which also funds Global Sisters Report.)

Since 2016, in an effort to recruit and keep young talent, companies like Fidelity Investments, Penguin Random House and Aetna have rolled out debt-repayment programs alongside their more traditional benefits like medical and dental insurance. This means, Loftus said, that the church is now in competition with the secular world — which could be a problem if young would-be religious don't realize they have options to get out from under their student debt.

"What we're losing as a church is the energy and enthusiasm of young people," Loftus said. "Their good work is being deferred due to this [debt] burden."

Take, for example, recent fund grantee Sr. Graciela Colon, a Sister of Christian Charity and immigration lawyer. Five hours a week, Colon provides pro bono legal services at an immigration resource center in Morristown, New Jersey. Loftus said it's unlikely she could afford to volunteer her time in that way if she still had a mountain of student debt to pay off.

To ensure religious vocations seem as viable to young Catholics with student debt as secular jobs, Loftus — who came to the fund in May following a 30-year career in consumer marketing, most notably working on the popular "Got Milk" campaign — said his No. 1 job is advertising.

"We started out getting our house in order, if you will, and now we're really trying to get the message out about this need and help grow the fund so that we can have a viable and sustainable offering for years to come," he said.

The shifts in focus at both the National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations and Labouré shouldn't be taken as an indication that either program has been struggling. Far from it, Loftus and Flanagan said.

Last year, the National Fund for Catholic Religious Vocations gave out $250,000 in grants, mostly to future women religious. More significantly, Loftus said, although not everyone was awarded the full amount of money they requested, everyone who applied for a grant received one. In 2016, the fund began a new partnership with the National Council of Catholic Women that will raise grant money through its Vocations Purse Club.

In 2017, the society helped a record 37 people raise a record $1.2 million, Liz Bunnell, a Labouré spokesperson, wrote in an email to GSR. Twelve people began formation in 2017 thanks to Labouré, another record for the organization, and the society is set to help more people in the next five years than it has in the last 10, Bunnell wrote.

Flanagan said if Labouré is a success story, it's only because of God's grace.

"God is never outdone in generosity," he added.

Flanagan said people often want to know why he's in this line of work, especially given that he has to fundraise for his own salary. He tells them that having more religious and priests in the world is the gift.

"Think of what's the impact of what one sister does in her life. What one priest does in his lifetime. The number of sacraments, the number of religious ed classes taught, prayers said," he told GSR. "It's innumerable. We can't really put a tag onto it."

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]