A man pulls a cart of recycled material past a mural that says "From the heart comes peace" in Bogotá, Colombia, Nov. 22. Though 2016 peace accords put an end to the decadeslong conflict between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the government, Colombia's poorest, many in rural communities, still suffer violence, said Dominican Sr. Diana Herrera Castañeda. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Consider what you need to live with a sense of security and dignity. Reflect on the fact that some people must live with constant fear for the safety of your family members; how would this affect you?

Like many countries in Latin and South America, Colombia suffered from an oppressive government, which gave rise to antigovernment groups and to violence and conflict; many innocent civilians were often caught up in the violence. What would it be like to live for years in such insecurity? How do people heal after losing loved ones to such violence?

In Colombia's conflict, women religious provide 'opportunities for life'

By Rhina Guidos

BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA — Sr. Diana Herrera Castañeda still remembers those tense weekends from her childhood in Bogotá.

"It was the time of Pablo Escobar," Herrera said. "I was about 9 years old. On Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays, starting at three or four in the afternoon, one could hear bombs everywhere. And you were at home — with your parents, with uncles — always in fear."

The concern was even greater if a family member was away from home.

Years later, as an adult and a sister of the Congregation of St. Catherine of Siena, she realized that what others suffered at that time had been much worse than the anguish that permeated the city.

"It's very different when you hear the story of the people from [rural areas], where they were displaced," she said. "I had the opportunity, seven years ago, to work with two associations of peasant women. ... They told how their mothers would hide them at night to prevent the illegal armed group from [taking] and raping them and [from] taking their sons away as recruits."

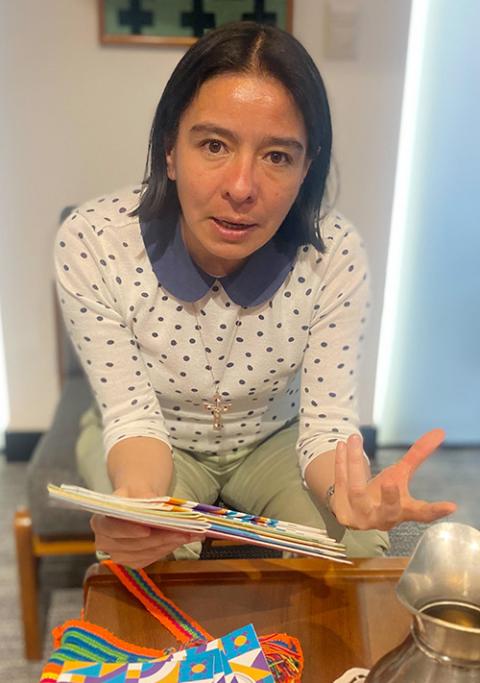

Dominican Sr. Diana Herrera Castañeda explained on Nov. 22 in Bogotá, Colombia, the role women religious have played in the country's peace process. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Now, as an academic, Herrera studies the role of religious sisters in Colombia's more than 50-year conflict.

"One begins to find that female religious life has played a very important role in accompaniment, and, above all, accompaniment in the most violent places, where people expressed resistance," said Herrera in an interview with Global Sisters Report in Bogotá Nov. 22. "It is a story that I feel has remained silent and hidden."

Perhaps religious sisters have not been present at the dialogue tables between opposition groups, like members of the church hierarchy have in Colombia, something that resulted in the signing of peace agreements in 2016. But with their ministries and presence in towns that suffered near and far from the capital, nuns have contributed to the peace process in an intimate way, Herrera said.

On many occasions, they have taught others "to see this moment of pain, of anguish, in a different way, to redefine it through productive projects," she said.

In some places, women religious have helped recover the historical memory of what happened in areas that suffered disproportionately from the war and, in some cases, where the conflict still lingers.

In places like Chocó, Antioquia and Granada, sisters, through sewing and baking projects, have given victims the opportunity to channel their pain, or physically participate in an activity that helps them meditate, then talk and heal from their losses, from the abuse. Sometimes, for the sisters, that takes the form of sitting down to participate in a craft and reaching out to people who haven't been able to talk about their traumas before, Herrera said.

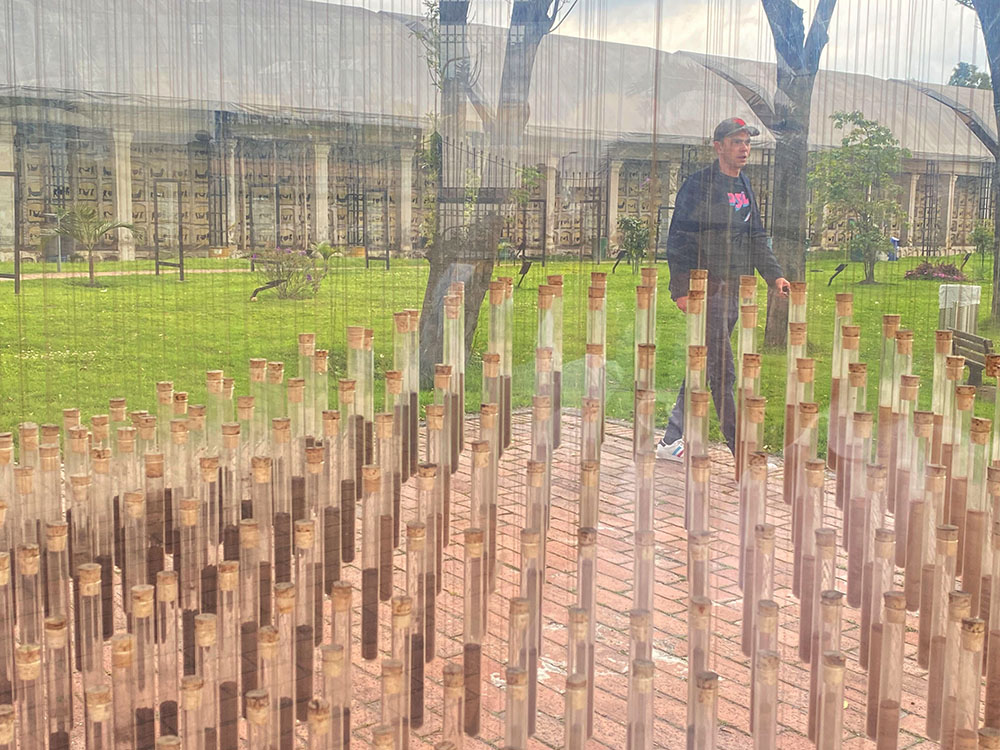

A visitor to the Center of Memory, Peace and Reconciliation in Bogotá, Colombia, walks Nov. 22 past an installation of vials filled with soil from the country's towns and cities that suffered violence during the decadeslong conflict between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the government. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"You sit down to sew with [the person]. And it is very beautiful because then sewing is not simply an activity. ... It's taking the portraits of missing persons and crocheting them, taking the name of a missing person and decorating it with flowers or symbols," Herrera said.

And in Colombia, stories of pain and violence, and people who need healing, abound.

In some places, such as the Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation in Bogotá, you can hear stories of the war, such as that of Gloria Inés Alvarado. Her eyes still sparkle when she sees the photo of her beloved son, Luis Alejandro Concha Alvarado. He was an extraordinary violinist, Alvarado said, focused, at the age of 23, on his philosophy studies at the Free University of Bogotá. He was days away from leaving for Paris, where he had received a scholarship to continue his studies.

"I don't think my son was perfect, but he was extraordinary as a human being, as a person, as a family member, as a companion," Alvarado said, contemplating his image in the middle of an exhibit, Nov. 22, that included photos of her family. "But the news that broke worldwide on April 16, 2006, alleged that my son was a terrorist."

For his mother, Luis not only became another victim of the armed conflict that day, but also a victim of the state's lies.

Left: Gloria Alvarado stands on Nov. 22 next to a photo of her only son, who was assassinated, and whose killing and its consequences is now part of an exhibit at the Center of Memory, Peace and Reconciliation in Bogotá, Colombia. Right: Alvarado explained to GSR the work of art that depicts how her eyes could not have seen the danger her son was under. She said no one has taken responsibility for his killing. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Government officials suggested to members of the press that Luis and three other students, who died with him during an explosion in the building where his family lived, were assembling explosives to help the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, known as FARC, in conflict with the government at that time.

Despite the insinuations, officials never presented evidence nor investigated the incident, she said. The only thing they did was sow doubt and pain for the family, as well as for thousands of Colombians who still seek answers about the deaths and disappearances that transpired during the conflict.

Illustrating the pain that many like Alvarado carry with them day after day, the final report of the Truth Commission (published in 2022) revealed what "women had to witness," Herrera said. "How they entered their homes, killed their husbands, took their sons, and raped their daughters. ... And not only the illegal groups. Unfortunately, the army also took part in all this."

What is not disclosed, Herrera said, is the dedication of many religious sisters during those times, some of whom have been very visible, such as the case of Sr. Maritze Trigos Torres, a Dominican Sister of the Presentation.

Trigos, a human rights defender for more than 30 years in different places of conflict in Colombia, speaks in a 2019 YouTube interview about her "option for the one who needs the most, for the one whose human rights have been violated."

Trigos "helped teach people how to exercise their right to petition, taught people how justice works in Colombia, and [how to] speak up," Herrera said. "She was part of a search unit for a group of missing people and went to help find the bodies of the people who'd been killed."

Herrera said there are also cases of sisters like Yolanda Cerón, of the Company of Mary, shot dead by paramilitaries in September 2001 in front of a church in the urban area of Tumaco, Nariño, situated in southwestern Colombia.

Like Trigos, Cerón saw the need to join the resistance and helped those around her, many of them Afro-Colombian and Indigenous, to defend themselves, Herrera said.

"Illegal gangs are emerging, as well as drug trafficking groups ... and so they had to denounce the Colombian state, and that was when the whole mess began because the state itself began to go against them," Herrera said.

During the toughest days of the coronavirus pandemic, when many activities were carried out virtually, Herrera had the opportunity to listen to reconciliation talks from a region accompanied by sisters during the conflict, she said. She heard stories of what she calls "accompaniment in silence" from sisters who visited families, who were with them in mourning the death or disappearance of a loved one, or how they helped people escape clandestinely.

Two men read the text of letters written by those who knew victims of Colombia's civil conflict, while walking the grounds of the Center of Memory, Peace and Reconciliation in Bogotá Nov. 22. The letters express the pain of those who suffered the loss of their loved ones or who don't know, decades after their disappearance, what happened to them. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"There are religious communities who hid people in their homes, in their convents, in their communities, so that they could escape" and survive, she said.

She also heard about a community of women religious who dedicated themselves to single mothers-to-be so that they would not have abortions, as some did not want to give birth amid the conflict.

"They took them in and said, 'No. Come. We'll give you support, but don't abort,' " and they accompanied them, even when the time to give the child up for adoption came.

Colombia continues to have problems despite having signed peace agreements. The war, in some places, for the poor and distant and rural towns and cities, is still going on, Herrera said. So the sisters' work also continues.

"That is where religious life begins to make more sense, from its social side, to say, 'Our task is to listen, to help people find their way, not so much to heal, but to help them see that there are other opportunities, for life,' " and proving that life, no matter what happens, can go on, she said.

What are some of the ways Catholic sisters showed compassion and strength during the decades of conflict in Colombia? Why should the sisters' stories be uncovered and made known?

Like other countries in Latin and South America during the last seven decades, Colombia had many people who "disappeared" during times of violent repression and resistance. How does not knowing what happened to loved ones impact their families?

Why have women gotten so involved in the peace process in Colombia?

What methods of healing do the sisters use today for individuals who suffered and for families who lost loved ones in the long conflict? Why is this work important?

The great Prophet Isaiah declared: "Seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow" (Isaiah 1:17).

When Jesus "was handed a scroll of the Prophet Isaiah," he found and read these words: "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring glad tidings to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free" (Luke 4:17-19).

How does Isaiah, and Jesus — using the words of Isaiah — define the Savior's mission?

As followers of Jesus Christ, how do these words challenge us to go beyond our own concerns? How do these words relate to the ministry of the sisters in Colombia?

The U.S. Catholic bishops say that because everyone is made in the image of God and thus every human being has dignity as a child of God, "the Catholic tradition teaches that human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Therefore, every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency."

In June 2025, Pope Leo XIV said that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is part “of humanity’s cultural heritage” (echoing Pope St. John Paul II) and these rights place "the human person, in his or her inviolable integrity, at the foundation of the quest for truth.” Human rights promote the dignity of every human person.

Why does our church uphold and promote the concept of rights belonging to every human being? What human rights are necessary for individuals and communities to survive and to develop fully and to flourish?

What specific human rights can you name (or look up)? Were any of those rights violated in the political situation in Colombia that motivated the Catholic sisters to become involved? What do you know, or can find out, about St. Óscar Romero's ministry amid the human rights violations in El Salvador?

The sisters in Colombia displayed spiritual strength in standing with the victims of violence during the many years of conflict in that country. They display steady perseverance in working to help people heal from the loss of loved ones to violence. Can you think of ways to become more grounded in your faith so you, like the sisters, can develop strength and perseverance to help others? How can these sisters be a role model for you as you grow in your faith?

Learn more about human rights — see the Maryknoll sisters and the Maryknoll community's social justice site: https://maryknollogc.org/issues/human-rights.

Follow Human Rights Watch's issues and suggested advocacy actions: https://www.hrw.org.

We pray that all people of faith in this world recognize we are our sisters' and brothers' keepers, and thus we are all connected with sacred bonds. We pray that we have the spiritual strength to respond to the call to create a world where peace, justice and healing are possible because human rights are fully supported. Hear our prayers, O Lord, hear our prayers. Amen.

Tell us what you think about this resource, or give us ideas for other resources you'd like to see, by contacting us at [email protected].