Hanaa Abdullah poses with her children and her brother's children in her brother's apartment in Madaba, Jordan. Abdullah and her brother both fled Syria and now live in rental apartments in the city but have difficulty making ends meet and getting the services they need. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Reflect on your own or with a partner on the following questions. These will help you to connect with the story you're about to read.

- In your experience — or based on what you have heard — how do people respond when refugees from other countries come to their communities? Why?

- Based on the title of this story – why do you think people in Jordan might want to help the Syrian refugees, but don't want them to stay?

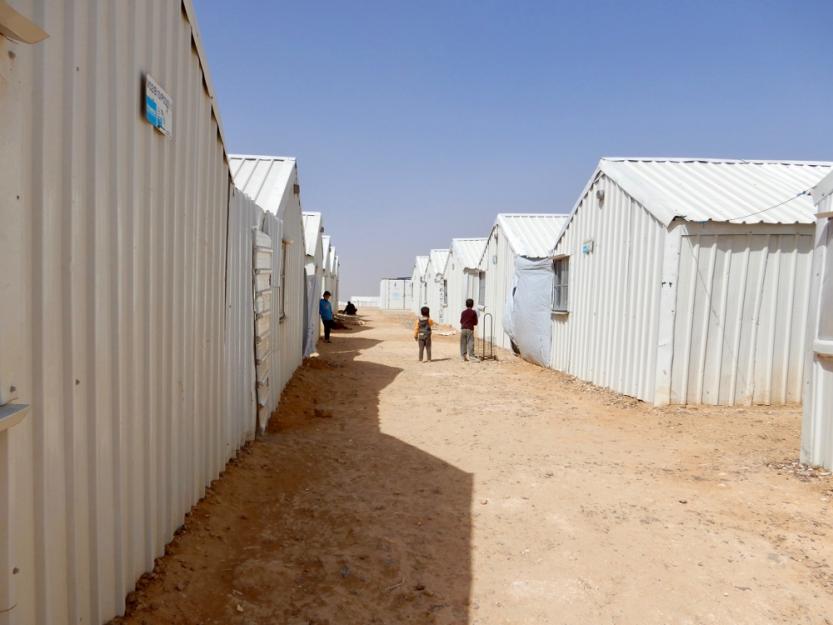

Azraq refugee camp in Jordan was entirely planned and constructed before the first refugees arrived in May 2014. It has 10,479 corrugated metal shelters carefully organized in neighborhoods and blocks. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

What is the best way to meet the needs of refugees? (This article describes a few different approaches, with the pros and cons of each.)

Seeking Refuge: Jordan takes in masses of Syrians but prefers they don't stay

Jordan's Azraq refugee camp is located in the desert. Without a tree in sight, everything in the camp is brown, coated by a desert dust so widespread that even the beige-tinged sky seems to hang low and close.

In perfect rows, three meters between each building, 10,479 metal huts break up the horizon.

Azraq Camp is the pride of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Usually, refugee camps are chaotic and messy, with desperate people building makeshift accommodations wherever they can. But Azraq is different. It is one of the world's first refugee camps planned, constructed and finished before the first refugees arrived, designed as carefully as a 1950s American subdivision.

Azraq's well-organized layout has many benefits. Residents have easy access to health care, education, cash assistance and subsidized food at the World Food Project hangar, a huge supermarket. Around 35,000 people are registered in the camp, which opened in May 2014.

A family's shelter in the Azraq refugee camp is outfitted with a material that minimizes the searing heat in the summer and provides some protection from the cold in the winter, but there is no electricity. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Most Syrian refugees in Jordan do not live in places like Azraq. According to the U.N., 81 percent of refugees in Jordan live in urban areas, finding housing in cramped apartments, working informal jobs that pay in cash, doing their best to get by in the crowded streets of Amman and other cities.

Refugees scattered around the cities have much more difficulty obtaining services. Although they also receive refugee identity cards and can get the same support as those in the camps, it is more challenging to inform them of their rights and ensure they receive them.

While large international organizations provide services at refugee camps, many urban refugees are falling through the cracks. As the war in Syria drags on and the refugee situation shows no sign of easing, sisters and Catholic organizations in Jordan are concentrating on aiding city refugees, trying their best to connect them to as many resources as they can, or just lending an understanding ear.

A history of welcoming

Throughout history, Jordan's blend of hospitality and political stability has made it the destination for wave after wave of refugees. First the Palestinians came, in 1948 and 1967, following wars with Israel. Today there are more than 2 million Palestinian refugees in Jordan who have full citizenship. Culturally, they still identify as refugees, though international organizations no longer consider them as such.

Iraqis and Kuwaitis came during the Gulf War in the 1990s, then more Iraqis came in the early 2000s after the American invasion and again in 2014 when the Islamic State group terrorized their country.

Since 2011, more than 655,000 Syrian refugees have streamed across the border, escaping an eight-year civil war. In the beginning of 2018, Jordan had 740,000 refugees, according to UNHCR

Jordan has a 16.5 percent unemployment rate, and the number of residents living under the national poverty line climbed, from 13 to 14 percent over the last decade, according to the World Bank.

The desert country of 10 million people is quickly running out of water and doesn't have the natural resources for the swift population growth resulting from the influx of refugees. According to U.N. data, Jordan's rate of accepting Syrian refugees in the last decade would be equivalent to the United States adding more than 20 million into its total population. In fact, the U.S. has admitted only 21,205 Syrian refugees since 2002, U.S. State Department data shows.

Welcome to visit, but please don't stay

Like many other countries, Jordan severely limits the ability of refugees to work, in hopes that they will soon return to their home countries. The country reluctantly issued 46,000 work permits for refugees in 2017, but the vast majority of refugees cannot legally work. This thrusts them deeper into poverty and makes them more dependent on international organizations.

Another part of Jordan's strategy to ensure refugees don't stay is to assign them to live in Azraq. The basic accommodations and sheer boredom make many residents consider the camp an open-air prison. Zaatari Refugee Camp, a larger camp only a few miles from the border, has a bustling economy and a main street where enterprising Syrians have set up businesses from hair salons to bridal studios.

But in Azraq, the camp's U.N. directors tightly control every aspect of life. They decide who can run stores and where the public can gather. They are installing a cash benefit payment system that reads the iris of the eye, like something out of a science fiction movie. Refugees must obtain permission to leave the camp.

"Azraq is not a pop-up camp that people came and immediately settled," said Emanuel Kenyi, an UNHCR official. Kenyi is originally from South Sudan but spent most of his life as a refugee in Uganda. "Azraq was planned for a year before the first people moved in. As Zaatari was getting filled up, they started planning Azraq before the refugees arrived."

Jordanian authorities are trying to convince urban refugees that life will be easier in the camp, so as to prevent situations where refugees assimilate into city life and decide to stay. Many refugees struggle to pay rent and feed their families in the cities, where services are harder to access.

The Caritas clinic in Amman is one of the places where urban refugees can obtain subsidized health services under agreements with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

A child-friendly space in the Caritas clinic in Zarqa, a suburb of Amman, gives parents the opportunity to go for medical appointments and consultations without worrying about what to do with their children. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Stepping in to fill the gaps

Urban refugees are spread out and busy trying to figure out how to survive, requiring more personalized solutions.

In many ways, sisters are uniquely positioned to address the unique needs of these refugees because they are integrated with the community and familiar with Catholic organizations providing aid. In Zarqa, a suburb of Amman, Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine of Siena run the Pontifical Mission Mother of Mercy Clinic, which provides prenatal care and vaccines for more than 1,000 people every month.

The clinic opened in 1989 next to a Palestinian refugee camp with the goal of helping the displaced. Today, it provides heavily subsidized medical care to refugees and foreign workers from Afghanistan, Chechnya, Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Bangladesh, in addition to impoverished Jordanians.

The Dominican sisters are themselves refugees from Iraq, forced to flee in 2014 when Islamic State militants attacked the area of Nineveh. The congregation lost 33 convents, three schools and six kindergartens in bombings across Iraq, according to Sr. Habiba Toma Binham. The refugees they serve know the sisters are intimately familiar with the pain of losing a home and facing an uncertain future, Binham said.

Dominican Sr. Habiba Toma Binham, left, and Sr. Maryan Nahla Kame in the records room of the Pontifical Mission clinic in Zarqa, are refugees themselves, having fled Iraq in 2014 when Islamic State militants attacked the Nineveh area. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

The clinic frequently treats psychiatric diseases and psychosomatic issues when refugees complain of pain that doesn't seem to have a biological explanation.

"They are worried about their lives and future," said Rasha Altoum, a social worker at the clinic. Altoum is a third-generation Palestinian refugee. "They come here to be comfortable, because we give them the chance to talk freely without fear."

Altoum recalled a young Iraqi girl who came to the clinic, eyes tightly squeezed shut, telling the sisters she had gone blind. "Her family was always thinking about leaving [Jordan to go back to Iraq], and she was scared so she reacted by kind of going blind," she said. "So we let her speak about what she's feeling. We asked, 'What are you afraid of? What can we talk about?'"

'We were all once refugees'

Many sisters find common threads among the refugees' challenges, regardless of where people come from. One is an insistence on getting immediate help, stemming from overall uncertainty and instability.

"People in need are always angry," said Soheal Abbassi, the supervisor for Caritas in Zarqa. "They have their needs, their kids' needs, they have to pay the rent, they are really worried and scared. We tell them, 'We are trying to help you, but nothing is for sure.'"

Caritas runs 22 centers across Jordan, focusing on health and education. Caritas also provides remedial tutoring service and runs "catch-up school," an afterschool framework for Syrian children who couldn't gain admission to government schools because of severe over-enrollment.

Abbassi said Jordanians know the situation for refugees is desperate and are trying to be welcoming. "There's some, maybe not anger, but they are wondering, 'Why isn't the help going to us, why are all the non-profit organizations working with refugees,'" Abbassi said. Jordan requires NGOs working with refugees to dedicate 30 percent of their programming to Jordanians in need, but there is still some resentment.

"There's also less assistance coming now," Abbassi said, pointing out that international donors have tired of the Syrian conflict. "So there's less for refugees and less for Jordanians. So now everyone is angry because there's less for everyone."

And Jordanians know the situation isn’t likely to change soon. "Last year, people were saying it will be calm in Syria, but it's still not safe to go back," said Abbassi. "We know it will be at least two to three years until everything is safe."

Even when the violent conflict is over, that doesn't mean the flow of refugees will stop, as survivors find it is impossible to make a living in the shattered country. "Today, there are still new refugees coming from Iraq, and it's been 20 years since the first war," said Abbassi.

As sisters and international organizations try to create a safety net for urban refugees, they also point out that their most important role might be just to listen.

The Hashmi neighborhood is a rough corner of Amman, with about 200 Iraqi refugee families as well as Egyptians who work illegally in construction. Sr. Carmela del Barco, a Dorotea sister originally from Italy who has been in Jordan since 1975, said the arrival of a wave of Iraqi refugees four years ago turned the sisters' convent into an informal counseling center.

The sisters' official ministry in Hashmi is running a school for 500 students from first through 10th grade as well as leading catechism and religious discussion groups. But a large part of their time is also spent sitting in their living room or visiting parishioners in their homes, listening to their stories and trying to help them however they can.

"We do small stopgap measures," said Sr. Rania Khoury, one of the three Dorotea sisters, known formally as the Sisters of St. Dorothy, Daughters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, in Hashmi. “They like to come here to speak, it's a very important spot for them. We are near the church... We can't do everything, but we try to help families with sick babies and children."

On some months, international donations allow them to provide diapers and formula for 150 babies or help a family pay for a medical test.

"When we have nothing, we try to listen so they can feel better," said Khoury. "If you just listen so they can express everything, they feel better than before. They leave here feeling calmer."

The Sisters of Sr. Dorothy used to have a presence in Syria, but after a sister was killed in a 2013 bombing, the congregation left.

Left: Dorotea Srs. Carmela del Barco and Rania Khoury are in their sitting room in Amman's Hashmi neighborhood, which has turned into a de facto counseling center for the approximately 200 Iraqi refugee families who arrived over the last four years fleeing the Islamic State. Right: Sr. Hanne Saad, a Franciscan Missionary of Mary volunteer at Caritas in Amman, helps Syrian and Iraqi refugees get medical tests and medicine. (GSR photos / Melanie Lidman)

The most important thing

Some problems are impossible for the sisters to solve, so they can only provide emotional support.

"Just being with refugees, that is the mission," said Sr. Hanne Saad, a Franciscan Missionary of Mary who volunteers with Caritas in Amman and works mainly with Syrian and Iraqi refugees. "We don't need to talk. We need to listen."

Saad said the biggest challenge is the refugees feeling helpless and depressed because they cannot work. "They have the energy to work but they can't," she said. Those are the kinds of problems the sisters can't solve. Still, they try to strengthen the refugees. "We have hope in life, because if you don't have hope, you don't have life," she said.

That is the hope that Hanaa Abdullah, a tailoring teacher who fled a village near Deir ez-Zor, in eastern Syria, clings to every day. She lived in Azraq camp with her husband and three children for seven months in 2016 before they were able to secure a permit to live outside the camp.

"The first months in the camp, I was just sitting and crying," Abdullah said. "When I wanted to get out of the camp, I got help. I'm happy to be out. It's better for the children's psychology, education. And life is better here."

After moving to Madaba, a large city south of Amman, the family had new challenges: how to pay for rent and electricity, how to enroll the children in school, how to collect the cash assistance awarded to refugees, where to get health care. She gets text messages irregularly from the U.N. refugee agency.

"I try to be as strong as I can in order to be in a better situation," she said. Her daughter, Joud, 10, is still traumatized from the plane bombings that destroyed their hometown. "When we first got here, whenever Joud would hear a plane she would put her head in my lap and start shaking, covering her ears," said Abdullah. Now, Joud is less scared of planes, though the family is still trying to adjust to their new lives in Jordan.

"The biggest happy story for us is that we're together as a family," Abdullah said. "The rest is less important.”

A nurse at the Pontifical Mission Mother of Mercy Clinic in Zarqa weighs a young Syrian refugee ahead of his vaccinations. The center vaccinates more than 1,000 children per month. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Reflect on your own or with a partner on the following questions.

- The sisters are providing important services to refugees. How has their own history made them better able to care for the refugees?

- Do you think it sounds mean or cruel that Jordanians don’t want the refugees to stay, or does their attitude make sense to you? Why?

Jesus showed a true love for outsiders and people in need. Near the end of his time on Earth, Jesus tells his disciples in Matthew 25:31-40 that people will be judged based on their love and care for the least among them.

"When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit upon his glorious throne, and all the nations will be assembled before him. And he will separate them one from another, as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will place the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. Then the king will say to those on his right, 'Come, you who are blessed by my Father. Inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me.' Then the righteous will answer him and say, 'Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? When did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? When did we see you ill or in prison, and visit you?' And the king will say to them in reply, 'Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.'"

- Why can it be difficult to see Jesus when we look at strangers and people in need?

- Beyond meeting their needs, what good can come of our efforts to reach out and serve refugees and others?

Pope Francis recently shared a special message with the young people of the world. In Christus Vivit, he observed how people might ignore or shun migrant people and their needs. Here’s part of what he said:

Nor must we overlook the particular vulnerability of migrants who are unaccompanied minors, or the situation of those compelled to spend many years in refugee camps, or of those who remain trapped for a long time in transit countries, without being able to pursue a course of studies or to use their talents. In some host countries, migration causes fear and alarm, often fomented and exploited for political ends. This can lead to a xenophobic mentality, as people close in on themselves, and this needs to be addressed decisively.

- Xenophobia — a fear or prejudice against people from other countries — is common in our world. Where and how have you seen it happen?

- The pope's call for decisive action isn’t limited to governments and nonprofit agencies. How can you help prevent the spread of fear and alarm about migrants?

Consider the unique gifts that sisters in this article bring to their work.

- Why might refugees struggling with loss and uncertainty have special reason to trust the Dominican sisters?

- The Sisters of St. Dorothy sometimes can do little more than listen to refugees. Why is listening such an important gift to people who have many great needs?

- Explore more about the most common medical problems that migrant people face. How are they prevented and cured? Discover a group that addresses these problems and consider ways to support it.

- Reach out to a lonely person in your school or community — perhaps a new kid at your school or an older person in a care facility. Let them tell your story to you, and do your best to listen.

- Alone or with a group of friends, make an effort to greet one stranger every day for a week. Reflect on how your efforts might change their lives — and yours.

Open our hearts, Lord, to serve and love the strangers among us.

Tear down the walls and borders that keep us from reaching out freely to people in need.

Inspire to see your face in theirs and love them as we love you.

Amen.

This article comes from the series "Seeking Refuge," published by the Global Sisters Report. You can download the entire e-book HERE.

Tell us what you think about this resource, or give us ideas for other resources you'd like to see, by contacting us at education@globalsistersreport.org