"Polé, polé" is a Swahili phrase that means "slowly, slowly," and it's one you'll hear over and over when you climb Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa at 19,431 feet (5,895 m) above sea level. The human body can't survive at altitudes that high, but if you train yourself by going slowly up the mountain, you can enable your body to adapt to the low levels of oxygen that make high altitudes so difficult.

Mount Kilimanjaro is not a technically difficult peak. The challenge is mental: You must believe that you will get to the top. If you go slowly enough — polé, polé — you most likely will.

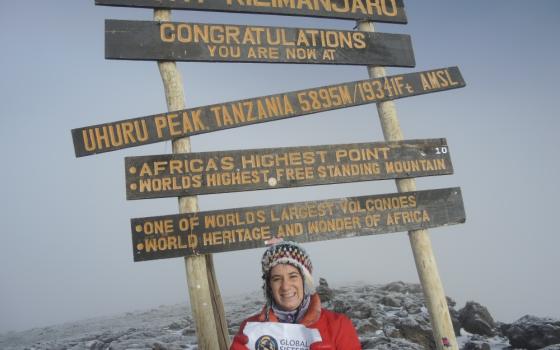

During a recent reporting trip to Tanzania, I decided to take some time as a tourist and climb Mount Kilimanjaro with Tro-Peaks Adventures. I hiked via the Machame Route, a seven-day climb. Each day of the hike, you pass through a new temperate zone, from temperate rainforests to moorlands to alpine deserts to glaciers. There's a lot of time for contemplating as you weave through lava fields and past 200-year-old senecio trees.

And I had a lot to think about after spending two weeks in Tanzania, reporting for Global Sisters Report. Tanzania has the distinction of being the country with the most sisters in Africa: There are approximately 14,000 sisters in this country of around 50 million. Neighboring Kenya, which has a similar population, has 5,000 sisters.

This large number of sisters comes with many challenges. The education system in Tanzania is notoriously weak, and with so many members, congregations can't afford to educate all of the sisters. A sizable portion of the sisters do not have education beyond seventh grade, which can confine them to menial work such as cleaning, cooking or farming. The former general secretary of Tanzania Catholic Association of Sisters, Sr. Pacis Massawe of Our Lady of Kilimanjaro Sisters, said that sometimes, these uneducated sisters end up working as unskilled laborers for the dioceses, getting paid by the church as little as 10,000 Tanzanian shillings (approximately U.S. $5) per month.

Tanzania is made up of more than 120 different tribes, which were united into a single national identity through the work of the country's first president, Julius Kambarage Nyerere, after gaining independence from the British in 1964. One of the successful ways he promoted this united identity was through the use of Swahili as a national language.

Today, Tanzania does not suffer from the divisive tribalism that plagues Kenya and other countries in the region. Much of that is thanks to a strong national identity made possible through Swahili. But the universal use of Swahili also means that residents learn English as their third or fourth language, after one or two tribal languages and Swahili. Very few sisters in Tanzania speak English. This further isolates sisters from regional educational opportunities and conferences.

Tanzania is also struggling to develop. The average income is U.S. $1,900 per year, ranking the country 204th out of 230 countries, according to the CIA World Factbook. When I spoke about GSR to a group of 40 formators who are training the next generation of sisters, only six of them had Internet access. Of those six, only three had ever heard of the term "website."

I fervently believe that GSR can be an important resource for sisters, helping them learn from each other and connecting them with funds and opportunities. But as always with development work, the sisters who need these connections the most acutely are the ones who are the hardest to reach.

These were the thoughts running through my mind as I sat under a sky impossibly full of stars on our second night on Mount Kilimanjaro as a full moon rose over the snow-capped peak.

On the third day of climbing, we reached an altitude of 15,100 feet (4,600 m) in an acclimatizing hike before descending to sleep several hundred feet lower. After an exhausting eight-hour climb to the highest altitude I've ever reached in my life, I collapsed in my tent to rest. An hour later, I ventured outside for the customary tea and popcorn.

I exited my tent and was greeted by the most humbling sight. Clouds play hide and seek with the summit all the time, and when we descended to camp, the area was shrouded in mist. But suddenly, the clouds parted, and I saw before me a 1,000-foot (300-m) sheer wall, with the summit reaching impossibly higher beyond that. The vista was stunning, but I was crushed.

"How have we been hiking for so long and we are still so far away?" I thought to myself. "And that wall! That wall looks impossible to scale."

Aside from the misery and difficulty of the summit push, this was the lowest point for me on the trek. I felt physically exhausted, worried about the altitude, and doubtful I could hike for another four days. On top of that, I was nervous that my whole trip to Tanzania had been fruitless since it had been so difficult to make connections with the sisters, aside from a few administrators who had acted as my translators.

The next morning, I approached the wall with trepidation. But what had looked like a sheer wall from a distance on closer inspection was climbable through a skinny path that snaked up the side and wove its way through cracks and small ledges. The most exciting moment of the climb was the Kissing Rock, when you had to stand spread-eagle over a deep chasm, facing a rock so close you could kiss it, as you scrambled to the other side. Thank God I had just my small day pack and not the 45-pound (20-kg) bags that our inexhaustible porters carried on their heads.

Two hours later, I pulled myself up and over the plateau, putting the sheer wall behind me. The summit still seemed infinitely far away. Looking out over the clouds blanketing the land below us, I felt as if I was on an island surrounded by a white sea. "Polé, polé," I thought to myself. Wending and winding our way over the Barranco Wall, we had made it.

There are problems, like the lack of widespread Internet access in developing countries in Africa, that GSR cannot even hope to bring about. But we can approach the problem from a different angle, utilizing the tools already in place.

Many sisters in Tanzania and across the continent are starting to use smartphones. While pay-as-you-go Internet access means they aren't using these phones for browsing the Internet, they are using WhatsApp, a mobile messaging service that utilizes very little data.

So as an experiment, GSR will be launching a pilot program to offer a WhatsApp discussion group, which will offer text-only excerpts from articles on our website as well as questions for discussion. We're calling it GSR Africa:Connect.

I've never tried anything like this before. I don't know if it will be successful. But I've also never climbed a mountain like Kilimanjaro. Sometimes, the challenges in front of us seem impossible to scale, but on closer inspection, there's always a way up if you can get creative.

Africa:Connect is one way GSR is trying to adapt to the different realities of the many places where sisters work around the world. If you're located in the region, we hope you'll join us on the journey as we push ourselves to new summits with your guidance.

Polé, polé.

______

For the pilot program of GSR Africa:Connect, the group will be open to sisters in Africa. If the pilot is successful, we will expand to include more sisters’ discussion groups in other regions and for our other readers as well. If you are a sister in Africa, or you know of a sister in Africa who would like to join the discussion group, please contact Melanie Lidman at [email protected]. Download the WhatsApp application for your phone.

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the nation's leader as Joseph Nyerere.