Wilson stands at the front of the cafeteria wearing a bright red button-down shirt, jeans, and tan Chuck Taylors. He has a sincere face with bright eyes that exude both innocence and strength. His right hand clasps the microphone, and the left gestures or occasionally moves the cord out of the way as he shuffles back and forth. He is just over 5 feet tall and skinny as can be, but his presence fills the whole room. Twenty-five people sit at round tables, brows furrowed and eyes fixated in both interest and concern, as he tells his story.

Wilson is a 20-year-old migrant from a small mountain village in western Guatemala. He came to the United States nine months ago, and I recently met him at our local parish.

Although he is new to the community, he was the first to volunteer when I put out a request for someone to speak about immigration at a church on the other side of town. He told me he feels passionate about letting people know what immigrants go through, and it shows. His delivery is confident and measured, even though he has to stop every few sentences for me to interpret. One would never know this is his first time sharing his journey with an audience.

Over the last decade, I've been privileged to talk with hundreds of immigrants. Still, each new story brings my heart to its knees. The courage, the faith, the injustice, the heartache, the indomitable human spirit: All of it stops me in my tracks.

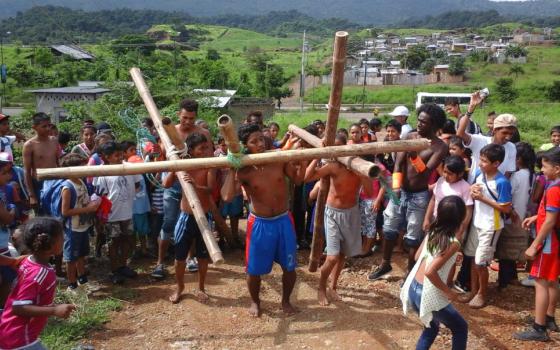

As I listen to Wilson on this week before Semana Santa, my heart hangs on each word. In awe, I realize I am hearing a modern-day Way of the Cross journey. While the rhetoric in our country would condemn Wilson as a criminal, I see that he is Jesus.

Wilson tells us he grew up "extremely poor but dignified." There isn't much work where he comes from, but somehow his parents scraped by enough to put a little food on the table every day and send each of their five children to at least a few years of elementary school. Wilson is the oldest, so he had to leave school when he was barely a teenager to help his family. He worked in construction, making the equivalent of $4 a day.

As Wilson approached his late teens, he worried more about his family and their town. His parents were getting older, and the expenses were growing. His younger siblings had to drop out of school.

On a wider scale, a foreign mining company was seizing surrounding land. It dammed off one of the main nearby rivers for use in the mine, and its operations were contaminating remaining water sources. Some people found jobs in the mine, but they were dangerous and disgracefully low-paying. As Wilson told me once, "Our world cares more about money than poor people like me."

After much soul-searching, Wilson decided to leave Guatemala. He knew the road ahead was treacherous; it's no secret that many have died on their way north. Like Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, Wilson had prayed in agony for another way, but risking his life in migration seemed the only choice. At 19 years old, he prepared to walk the path of sacrifice for love.

There is pain in his face as he tells us this part.

"It was a day of great sadness, the day I left," he says. "I hugged my parents and my siblings. I said goodbye to my friends. I don't know when I'll see them again." Like Jesus stripped of his garments, Wilson was stripped of all he knew and loved.

The first leg of the journey, he remembers, was getting to the Mexican border, where he had to pay off the gang-influenced immigration police to let him in. Sometimes, they steal the money and send the person back to Guatemala or kidnap them. Thankfully, Wilson made it through.

Then came days and days of walking or riding buses and trains through Mexico.

"I experienced hunger and thirst in a way I'd never known," Wilson says. "I was exhausted because I only slept a few hours here and there. I missed my family terribly."

All the way through Mexico, Wilson was vigilant, aware of his vulnerability as a stranger in a new land. When he finally got close to the U.S.-Mexico border, the most perilous part of his voyage awaited.

"We had to cross the Río Bravo," he tells us, eyes wide with the memory. Somehow, he made it across, even managing to escape U.S. Border Patrol agents on the shore by swimming downstream and hiding until they left.

He emerged, sopping wet and separated from fellow travelers, into the expansive desert, where disorientation overtook him. He walked for several days and nights with only a small ration of bread and water. After so much strife, this was like Jesus falling for the third time.

He thought he would die, lost and alone, when he miraculously encountered another migrant, a Simon to help bear the weight of the cross. Together, they found the highway and, later, the town where they could connect with coyotes to transport them through the interior United States.

Exactly 40 days after leaving Guatemala, Wilson had reached what he hoped would be his promised land. He called his parents to let them know he was alive. They had gone to bed 39 nights in a row unsure of their son's whereabouts or if they would ever hear his voice again. Tears flowed on both ends of the crackling phone line.

At this point in telling his story, Wilson stops and sighs.

"So, you see, people don't come to the U.S. for fun, or on a whim, or because they think they're going to take advantage of your luxury. It is a life-and-death decision to come here. I did it so that I could make life even a little bit better for my family."

Eventually, Wilson paid another coyote to bring him the rest of the way to Cincinnati, where acquaintances from his hometown are settled. He moved in with two friends, also young men here alone, and joined our parish. Just a few months after his arrival, he became the leader of our youth group.

In Wilson's hometown, his dad effectively runs the Catholic church; there are so few priests in the region that they have Mass only once every few months. Faith, service and leadership have always been central to their family.

Wilson is a hard worker. His friends helped him find a construction job in Cincinnati. The company only gives him four hours a day at $9 an hour, so he hopes to find a different job soon. Even with such a meager income, he manages to send money back to his family and chip away at the monstrous debt he incurred traveling to the United States. It costs thousands of dollars.

Even after such a long and treacherous passage, Wilson still carries his cross. The experience of living here in the United States, he says, is the most difficult yet. Every day, he feels the gnawing ache of being isolated from the people he loves most. He can't drive in the United States. He can't get a stable job where his dignity is respected. He knows the sting of racism and the angst of fear. With the most recent executive orders and prevalent anti-immigrant rhetoric, he worries that his 40 days on the road could be rendered void in an instant.

When an audience member asks about his status here, he says plainly, "I am an undocumented immigrant, afraid every day of being deported."

Still, he will not give up.

"My motivation for all this," Wilson says passionately, approaching the end of his presentation, "is my family. Right now, I'm sending one of my brothers to school. I didn't get the education I'd hoped for, but I want my younger siblings to have what I didn't have. I don't make enough for all of them to go yet, but I'm going to keep trying." There is deep, courageous love in his eyes. Tears of admiration well up in mine.

This Holy Week, I carry in my heart the millions of migrants and refugees for whom the Way of the Cross is not simply a spoken prayer but a raw, real reality. I venture to say Wilson knows the Passion story in his bones. Like Jesus, he is a man of great love. At just 19 years of age, he was willing to sacrifice everything for his family. Like Jesus before Pilate and the crowds, misguided people consider him a threat and would unjustly condemn him as a criminal. Like Jesus, he relies on God and trudges onward wholeheartedly. It is not in vain. The seeds of his suffering bring new life for others.

Wilson is Jesus for me. And Jesus, without a doubt, is for Wilson.

[Tracy Kemme is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati. Author of the blog Diary of a Sister-in-Training, Tracy is excited about the future of religious life! She currently ministers at the Catholic Social Action Office in Cincinnati and as Latino ministry coordinator at a local parish.]