My life begins in baby-girl pink, as is the custom of the day, and grows to soft pastel dresses with socks to match, or not, my mother's hands being full with two newborns at this point. When I get a weekend job at the cosmetic counter in Woolworth's, I buy my own wild and wacky teenage clothes.

Then I enter the convent. Here begins my life in black and white. Black-and-white clothes, black-and-white rules, black-and-white destination — heaven or hell.

I should have seen life's infinite shades of gray, being an English teacher. What is literature, after all, but the story of our muddling around in gray areas? When Emily Dickinson writes, "I dwell in possibility," she is not talking black and white. But it takes a dark room for me to see light.

And so it is. In the dark time of the year when light is stingy, I enter a photographer's darkroom, not unlike John of the Cross' la noche oscura, the dark night. I fumble in the dark, lit only with a small safelight, a reminder of God's ever-present love in dark places. At the enlarger, I project a negative image of Mary onto white paper, cropping here, enlarging there, like an ascetic choosing what to keep, what to discard. Then I slide the paper into an acid bath and bend over it, prayerfully. No incense here. I breathe in fumes and gently rock the tray; it's never easy to change negative into positive.

Finally, in wondrous awe, I watch a print of Mary emerge in black, white and infinite shades of gray that are more indicative of her life.

Don't be fooled by those folded hands, that placid face. Check her raised foot, the wild, wind-blown swirl of her garments. Mary is running to her cousin, Elizabeth, who is not running, being heavy with child and waiting for her cousin.

And Elizabeth's greeting? How is it that the mother of my God should come to me?

Mary, pregnant with the living God, replies: My soul magnifies the Lord. Magnifies. Enlarges. As if she herself is in a darkroom, or more accurately, is a darkroom where the Son of God himself is developing. Because nothing is impossible with God who dwells in infinite possibility.

The folds in Mary's garment are like the chapters of her life, from Nazareth to Bethlehem, Egypt, Jerusalem, Calvary. Her last recorded words are spoken at a wedding. Seeing the wine run low, she tells the waiters to do whatever her son tells them. Her son, it seems, had no intention of telling them anything. He, too, is developing in wisdom and grace.

Do whatever he tells you. Those words are engraved in every last fold of Mary's garment. They are meant for us, too. Do whatever he tells you in the darkroom of your soul.

They wrap his crucified body in long strips of cloth, round and round the corpse from neck to toe, then soak the whole shroud in redolent spices. They lay a separate cloth over his face, perhaps like a veil, like a black-and-white fact they cannot fathom.

On Easter day, two disciples run to his tomb. Entering with some trepidation, they find him gone and a heap of shroud with the smell of spice hanging in the air. The cloth covering his face is placed apart.

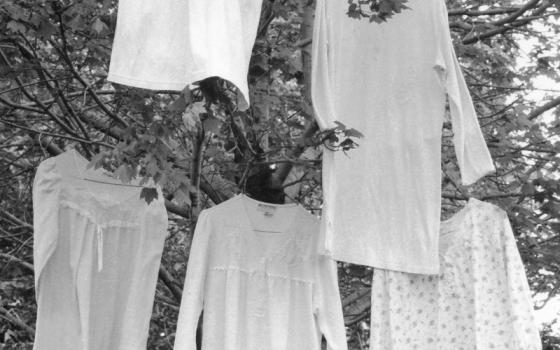

My mother dies three days before Christmas. We bury her two days later under winter snows. On Easter day, I hang her nightgowns on our backyard tree. The smell of her dusting powder clings to her garments as they rise in resurrection, as she has done, and Christ Savior before her.

Soon after, I bury a sunflower seed nearby. In time the seed breaks apart in its dark room and a tiny shoot lifts up. I water and mulch even as my mother's nightgowns flutter and rise.

In time, the sunflower is my height and I look into its face, much like Dante looked into the face of a rose. He saw paradise, a sphere with rows of petals representing the blessed. They whirled round and round the Divine Godhead dwelling in unfathomable mystery.

I look into a sunflower and see earth, rows and rows of leaves, each one a person remembered, quivering, beautiful. The whole earth lies in a sunflower. A morning offering lifted like a host.

[Joan Sauro, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet, publishes widely in the Catholic press. "We were called Sister" (U.S. Catholic) was awarded first place for Best Essay 2014 by the Catholic Press Association.]