When the artist Corita Kent left Los Angeles for Boston in 1968, everyone expected her to return. “She took what was supposed to be a sabbatical,” explains Ray Smith, director of the Corita Art Center – a gallery and archive located on the campus of the former Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, where Kent spent years as chair of the art department. “But she didn’t come back, and it’s a bit of a mystery why.”

It could have been the cancer, which dominated the last several years of Kent’s life and is, in part, credited for the introspective turn her artwork took in later years. The reasons were likely emotional. As one of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Kent was identified with the order’s very public battle with the Archbishop of Los Angeles at that time, Cardinal James Frances McIntyre, who opposed the order’s progressive political activism and lifestyle choices.

Smith says her move may have been spurred by a desire to get away from the publicity she unintentionally garnered as a result of the IHM’s tension with the cardinal. “She had become the public face of the whole protracted situation, but she was more comfortable making the banners than holding them,” says Smith.

Kent died of cancer in 1986, having never returned to Los Angeles to live. As with any great artist, though, her spirit is still alive in her artwork. For that reason, the significance of the Kent retrospective, "Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent," coming to Los Angeles this summer, cannot be overstated.

______

"Someday is Now" is the first full retrospective show of Kent’s work. Two years ago, co-curators Ian Berry and Michael Duncan debuted the show at the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, where Berry is a curator. The show has since been shown in museums from New York to Florida to Ohio, and finally last month landed at the Pasadena Museum of California Art in the Los Angeles area, where Kent lived and taught at Immaculate Heart College for most of her adult life. It continues through Nov. 1.

Berry says one of the main goals of the show is to introduce her work to new generations of artists and viewers. “She doesn’t come up enough in art history,” he says, “but those of us who organized the show think she is a critical part of American art history and contemporary art of the 1960s.”

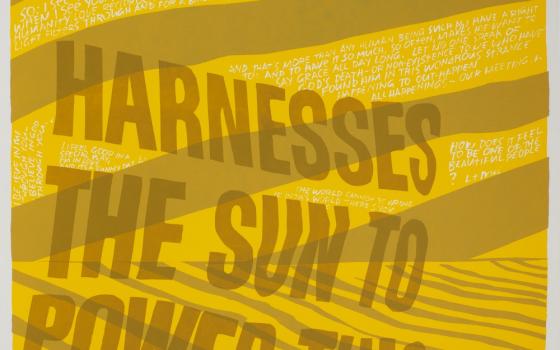

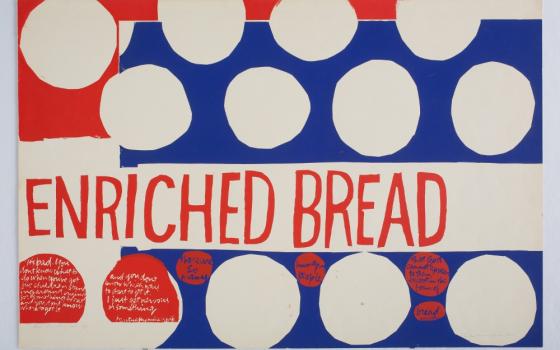

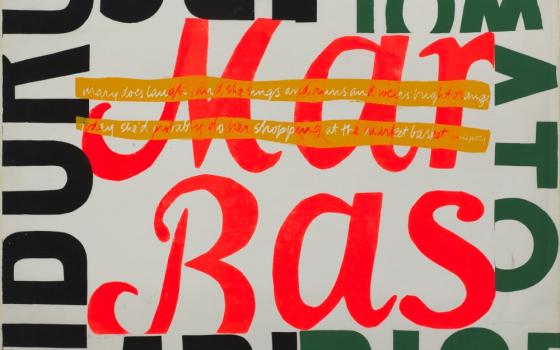

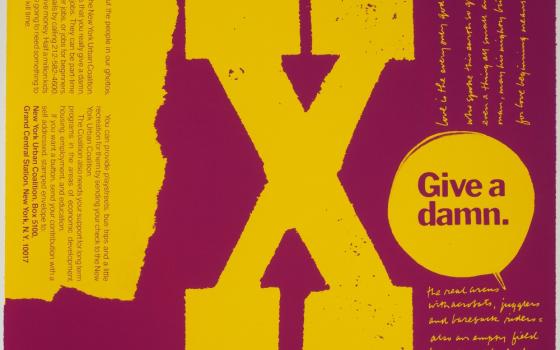

Much of Kent’s most well-known work uses bright, bold colors and a mixture of ad copy, often distorted in ways that make it look like it’s “flying through space,” according to Duncan, paired with handwritten messages which support her humanist perspective. The messages often take on her meaning under Kent’s lens. For example, her 1965 print, “Apples Are Basic,” features the handwritten text, “It’s a good sign when you admit you’re lost.” The text came from an American Oil advertisement, and had to do with car travel and getting lost, but with Kent’s treatment it seems to refer to the journey of the human soul.

As the first retrospective of her work, "Someday Is Now" was able to bring in pieces from two other periods of Kent’s art career: her earlier, more overtly religious work and her later, introspective work and simple watercolors. According to Smith her work stood apart as different from other religious artwork even from the very beginning. “At that point religious art of the 1950s was very clean, a lot of pastel colors and flowing robes. A lot of white people. Her work looked very different,” says Smith.

______

Kent joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary shortly after high school, following in the footsteps of family members – her sister was a nun and her brother was a priest. Throughout her life Kent credited this move with her becoming an artist. She told Newsweek in a 1967 cover story, “I probably would never have taken up art seriously if I hadn’t become a nun.” Indeed, she never received formal art classes until she entered the convent between high school and college.

Still, Kent was far from removed from the art world of the time. While she lived in Los Angeles, she traveled to New York yearly to visit galleries, says Smith. She was at the opening of the exhibition of Andy Warhol’s soup cans in 1962, among other important touchstones of the time. “A lot of people assume that these nuns were cloistered away and praying all day. That’s not accurate. She was not removed from the world or the art world at all.”

Despite that, according to Berry, her religious affiliation, along with the fact that she was a woman, might have hindered Kent’s ability to achieve the recognition in the 1960s pop-art movement that he believes she deserves. “Her being religious was not an easy match with the art world at that time.” After centuries of visual art’s primary purpose being to decorate churches and tell religious stories, Berry says, the “art for art’s sake” movement of the mid-20th century freed artists up to create anything they wanted – which may have soured some to work that was religious.

On the other hand, Kent’s work was considered too controversial for Cardinal McIntyre, says Smith. Her use of secular texts and advertisements was very nontraditional, and it didn’t sit well with the McIntyre’s conservative values. She was asked to refrain from depicting the holy family in her nontraditional aesthetic. However, Kent had found both a philosophical and spiritual home with her community – the order was known for its political activism and liberal views.

Eager to adopt changes brought by Vatican II, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary stopped wearing habits and began directing their own schedules for the day, and, for those nuns who were also teachers, negotiating their own contracts with diocesan school authorities, according the the Newsweek article. This did not sit well with McIntyre.

“Basically [the sisters] were given a choice from the cardinal to ‘be obedient women or nothing. Those are your only options. Leave or follow,’” says Smith. “That just did not work for the IHMs.”

Eventually the tension with McIntyre led to nearly all the sisters leaving the order in 1970 and reforming as the Immaculate Heart Community that it remains to this day. Kent herself had already left the order and moved to Boston in 1968, where her work initially became some of her most overtly political.

Kent routinely used her artwork as an outlet for political activism, calling for peace during the Vietnam War, racial equality and other progressive issues. “I am not brave enough to not pay my income tax or risk going to jail,” she once said. “But I can say rather freely what I want to say with my art.” The departure from Los Angeles freed her to do work that was more expressly politically active. For example, she used a Newsweek cover story with photos of Viet Cong being hunted, and juxtaposed it with a Walt Whitman poem that reads, “I am the hounded slave,” next to a picture of a slave ship and American soldiers.

Her last works, leading up to her death in 1986, were simple watercolors based on nature scenes. She left her work to the Immaculate Heart Community, where it is now housed at the Corita Art Center.

______

An art teacher at Immaculate Heart College during the 1960s, Kent encouraged her students to view the entire world around them as potential for the art they would create in her printmaking classes. She sent them to gas stations and grocery stories with thick pieces of card stock with small rectangles cut in the center – these were viewfinders, which her students used to frame the world around them, to see in ways they had never considered before.

“Her teaching methods were intended to break down fears of students who would say, ‘Oh I can’t draw.’ She was trying to get away from that fear of art making and open them up to really looking at the visual world and making their own expressive take on the visual world,” says Duncan. She was known for giving her students so-called “impossible assignments,” such as making 125 collages in one weekend. The goal was to get her students to break through the mundane and begin creating innovative work. “As you set out to make 125 collages the first two or three are going to be very conventional,” says Duncan. “But as you get more and more desperate you get more and more inventive.”

At the Pasadena Museum of California Art, a group of students from Kris Pilon’s screen printing class at Pasadena City College who were a field trip wandered through Kent’s prints. Many said they were inspired by her bright, bold color choices, some calling them “trippy.” Cindy Bui, one of Pilon’s students, said, “I’m totally jotting down color schemes. I think the way she used them was very, very effective.”

Some were surprised to learn she had been a nun. “You never see this kind of thing at church, in religious pamphlets, the bright colors,” said Vinod Ramaling, another of Pilon’s students.

Pilon said she hoped her students took some technical lessons from viewing Kent’s work – to consider using transparency to blend multiple colors, and to incorporate text in different ways. Mostly, though, she said she hoped Kent’s exhibit got her students to look at art, and life, in a new way.

[Georgia Perry is a freelance writer based in Oakland, California. She's contributed to several print and online magazines including, The Atlantic, CityLab, Portland Monthly Magazine and the Portland Mercury. She was formerly a staff writer at the Santa Cruz Weekly in California. Follow her on Twitter @georguhperry.]

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story stated that Corita Kent never visited Los Angeles after moving away. In fact, she traveled back and forth from Boston and Los Angeles.