This month, and probably for every October for the rest of her life, Haitian Sr. Evelyn Moliney will remember a time she would rather forget.

A year ago, Hurricane Matthew bore down on southwestern Haiti, threatening a large swath of coastal area, including the city and surrounding areas of Jérémie, the capital city of the department, or province, of Grand'Anse.

Moliney was working in the town of Marfranc, about 15 miles southwest of Jérémie, with four fellow sisters of the Congregation of the Little Sisters of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus. The sisters were helping care for 40 residents of a senior citizens home run by the Haitian congregation.

The sisters debated whether they and the residents should stay or evacuate — a common question when Haiti is threatened, as it often is, by a hurricane, and people try to gauge the storm's strength. The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere does not have good infrastructure and lacks an adequate system of public shelters.

The sisters thought the seniors' residence could withstand the torrential rains and winds.

It didn't.

During the evening of Oct. 3 and the morning of Oct. 4, the Category 4 hurricane packing sustained winds of 145 mph hit Haiti, blowing off part of the building's metal roof, as the storm continued through the night. The sisters prayed and comforted the residents, sprinkling the inside of the home with holy water even as rain poured into the building.

When it was safe, the sisters moved the residents to a police station and a local priest's home. But during the evacuation, a wall of the building toppled, killing one of the residents. "It was traumatic for all of us," Moliney said during a recent interview while in Baradères, a mountainous community in southwestern Haiti also hit by Matthew, though not as severely as Jérémie and Marfranc.

Even now, a year later, the trauma remains — something that Moliney is hesitant to talk about much. Prayer helps, she said, but the everyday difficulties continue. Many residents of the Jérémie area — like the senior center residents — are still in temporary shelters, though Moliney said this week that construction on the center will begin later this month.

"Most of the people can't rebuild, and there is not the means to do it," she said of many Jérémie residents.

That is just one of the many challenges facing a congregation still reeling from the loss of congregational members and devastation from the catastrophic January 2010 earthquake. "Our economic situation is precarious," Sr. Denise Desil, the mother general of the nearly 200-member congregation, told Global Sisters Report. "We need support to support others."

Still, Moliney said, "We felt encouraged to be part of the work of God's people," noting the solidarity and help during the hurricane that people in Haiti gave each other.

Aside from the earthquake, Hurricane Matthew is among the most serious disasters that have challenged the island nation in the last decade. The official death toll from the storm stands at 546 people, though as many as 1,000 may have died, local officials say.

In the weeks preceding the first anniversary of the hurricane, Haitians worried about new threats from hurricanes Irma and Maria, which pummeled other Caribbean islands. Maria brought some rain and flooding but luckily nothing worse; Irma largely spared the country, though farmers in northern Haiti experienced some serious losses, as the Miami Herald reported.

The anniversary of Matthew and the potential for new disasters prompted discussion among Haitians about the fragility of the country and lessons learned dealing with disasters. That talk continues as the United Nations designates Oct. 13 as International Day for Disaster Reduction to mark "the way that people and communities around the world reduce their exposure to disasters and raise awareness about the risks that they face."

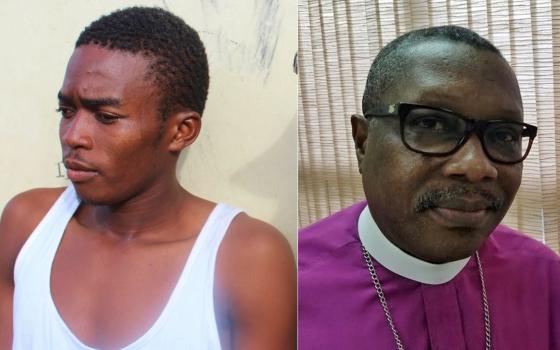

The after-effects of Hurricane Matthew are still being felt, as it "devastated many homes and crops along the southwest coast of Haiti; it also swept away livestock," Anglican Bishop Ogé Beauvoir, the executive director of the Haiti operation of the humanitarian organization Food for the Poor, told GSR.

It also came just weeks before harvest season, resulting in food insecurity, the inability to access food, which remains a "great challenge for many communities in Haiti," he said.

Beauvoir told GSR he is not worried that aid and donations being directed to other Caribbean islands as well as areas of Texas, Louisiana and other places affected by this year's hurricanes will have an impact on Haiti's rebuilding efforts.

American donations have already supported crop planting after the storm, plus a reforestation project, new chicken coops, bee hives and training for bee keepers, goats, fruit tree seedlings plus seeds to grow black beans, corn and other vegetables, he said.

As for lessons learned from Matthew, Beauvoir said there was a "lack of preparation at certain levels" which made it difficult to organize distribution of food "and reach the vulnerable population."

However, the bishop said that there are many effective regional community organizations in Haiti, such as the Association of Mayors of Grand'Anse, "which demonstrated their closeness to the communities they serve and which enabled us to broaden our field of distribution."

Beauvoir did not downplay other problems. Rebuilding after the devastation from the storm posed challenges, particularly in badly hit rural areas. Some Food for the Poor convoys were attacked, he said, and some storage facilities in Jérémie and the city of Les Cayes were robbed. But Beauvoir praised police for escorting some of the organization's convoys to areas needing food.

Overall, the biggest lesson learned from Matthew "is that the population needs to be better prepared to face natural catastrophes," he said.

Desil predicts that the other Caribbean islands affected by various hurricanes this year will be "rehabilitated" through their ties to other countries, such as St. Martin's to France. "It breaks my heart that we [members of her congregation] can't go to help them," she said in a recent interview.

Building stronger, reducing future risk

While there are plenty of resources in the world to aid nations rebuilding from disasters, she acknowledged that Haiti — while lucky so far during the current hurricane season — could face international "donor fatigue" if it were hit with a hurricane this year or in the near future.

Reflecting on "lessons learned" from Matthew and other major disasters, including the 2010 earthquake in which 220,000 people died, Desil said Haiti must construct sturdier buildings to be better prepared for disasters.

Desil knows the sorrow and agony stemming from the problem. Three sisters and a driver were killed when the congregation's small house in Port-au-Prince collapsed during the quake, and a fourth sister was killed elsewhere. And 122 students died when a congregational-run school in the western city of Carrefour collapsed. "It was terrible," Desil said.

Haiti has learned from the quake, she said, but there are always concerns about how well new buildings are actually being constructed and whether they could withstand damage from a major earthquake.

As for Hurricane Matthew, a number of clinics and other facilities run by the congregation withstood damage from the storm, faring much better than the seniors residence — though Jérémie and the surrounding cities were among the worst-hit from the hurricane.

Every hurricane season — roughly August through November — brings renewed anxiety in Haiti. "We always worry. We never know what will happen," Desil said.

When Hurricane Maria briefly threatened the city of Cap-Haïtien, the tell-tale graying skies and choppy waves made people anxious, particularly those living in low-income areas near the city's coastal front. The hurricane did not hit the city, though it affected part of neighboring Dominican Republic, which shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. "We worry a lot," said Watson Joachin, 24, a student and musician who lives in a river area of the city called Nan Bannann that often floods. "And we stay here because we don't have anywhere else to go."

When the situations get bad, Joachin said neighbors count on each other to provide food and shelter when needed. "We take care of ourselves," he said.

That feeling of solidarity — needed in a country where, for the most part, people do not count on any government aid, either from national or local authorities after a large disaster — was very much present in Jérémie and Marfranc after Hurricane Matthew, said Moliney.

That included both the help residents offered each other and the humanitarian aid from foreign assistance and donations received from other countries. Moliney compared it to experiencing heaven in the midst of hell. "That's exactly what it was," she said. "People helping each other."

That was crucial, she said, as is the persistent and unshakable belief in God's love for Haiti. "We always have hope," Moliney said. "We always believe in God, and we always believe we will come out of it."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is [email protected].]