As soon as the first sisters moved onto the church grounds in a rural region outside of Beijing, the babies started showing up on the doorstep. They were babies with severe disabilities, abandoned at a few months old, with no trace of the family who left them behind.

China's one-child policy was not enforced in the rural countryside, like here in Hebei province, where families continued to have an average of three or four children.

"These are very poor families, and these parents have a lot of pressure, not only for taking care of the disabled kids, but also taking care of many other children," said Sr. Niu Chun Mi, director of the Gaoyi Therapy Center for the Liming Family. The Liming Family is the primary ministry for the St. Therese of the Child Jesus Sisters, known locally as the St. Therese of the Little Flower Sisters. The Liming (House of Dawn) Family is a group of three institutions that serve children and adults with severe mental and physical disabilities.

"Parents began abandoning these children in front of the door to the church, and the bishop [Raymond Wang Chong Lin] asked the sisters to take care of them," recalled Sr. Xeufen Zhang. Xeufen was one of the original 10 founders of the St. Therese sisters in 1988, when Wang oversaw the re-founding of the congregation after China's Cultural Revolution had forcibly disbanded religious congregations.

"In the beginning, we kept the orphans in the same house as us, and we slept together, and we ate together," said Xeufen. "Before I entered the community, I thought that sisters live in a house with a big wall and pray all day. When I entered, I saw that a sister's life was very different. We needed to build the house ourselves, brick by brick! We needed to take care of these orphans and students. I didn't choose to be a mother, but suddenly I needed to be a mother and a father, too."

It wasn't until 1998 that the sisters formally opened the orphanage in a separate building, with guidance from sisters from Hong Kong, just after the Hong Kong sisters were allowed to make contact with mainland Chinese sisters.

Today, the Liming Family has three branches. Biancun Nursing Center provides accommodations for the youngest children who do not have families. The Gaoyi Therapy Center offers special education, speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and "integrative sensory" therapy, an occupational therapy for children with both physical and mental disabilities.

At the Ningjin Occupational Center for young adults aged 16 to 35, staff train the residents to make crafts that are sold locally and yield a small income.

"It started with the orphanage, but there were more and more orphans, and our former superior said we needed to reduce the number of orphans," said Sr. Ma Suling, superior general of the St. Therese sisters.

"Many parents don't want to abandon their kids, but reality forced them to," she said.

Resources and support for parents

The sisters started the therapy center in 2006, with the purpose of providing resources and support to parents, so they could keep their children at home. "Some hospitals accept these kinds of children for therapy, but it's very expensive," said Ma. "They need a lot of long-term therapy, even for years. If a child has cerebral palsy, they might need three to five years to learn how to walk with a device."

At the Liming centers, the therapy is heavily subsidized. Forty-minute sessions cost 25 yuan (about $3.50), less than 50 percent of the cost of hospital therapies. Families pay on a pay-as-you-can basis, but Ma said only about a third of the families are able to afford treatment. The rest is covered by donations from private individuals, including Catholics throughout China.

"We also do training work for the parents, and the parents often accompany the kids during therapy," explained Sr. Zhang Cun Cun, vice director of the therapy center in Gaoyi. "That's good for the long-term therapy for the kids."

"Teachers teach the kids to take care of themselves," Zhang added. "This reduces their expense to the families. They give them the therapies, and also personal hygiene. They teach them how to wash their own bowls and tie their own shoes."

It's a radically different approach from how institutions and the public used to treat people with disabilities, expecting that they couldn't do anything for themselves, the sisters said.

There are 130 children and young adults living at the Liming Family centers, which have helped more than 1,800 people since they started.

Changing society with stories and art

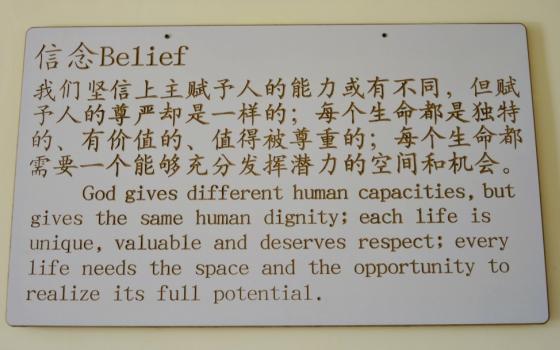

In addition to providing services for people with disabilities, the St. Therese sisters are trying to influence how society treats people with disabilities.

They have a speakers bureau that brings young adults from their center to tell community center and university audiences about their lives. "Their stories inspire a lot of people," said Sr. Mi Lihong.

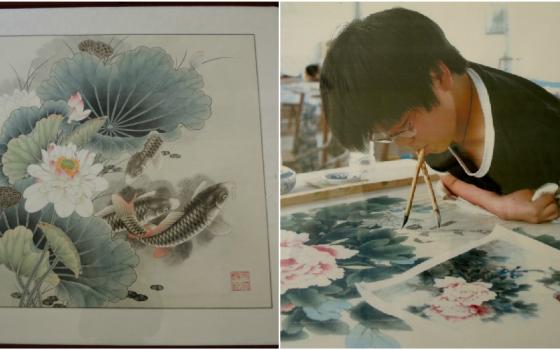

The Liming centers also organize talent shows, showcasing residents who can play the piano, sing, write poetry on a computer using their toes to type, or paint using their mouths. One resident, named Tian Herbal, is now studying on a full scholarship at Beijing Normal University. She does not have use of her limbs and paints stunning watercolors of giant flowers using a brush clamped between her teeth.

"Through these activities, we want the society to know our value of life, that we respect life like this," said Mi.

"After we leave a place, we don't know what happens but we hope what we told them affects them in some way, even if it's limited," said Tian Hua Hua, 23, one of the residents of the Liming Center. Tian, which means "gift from God," is the last name that the sisters give all of the orphans. Tian Hua Hua is part of the speakers bureau and a professional photographer. His work, featuring shots of intimate, spontaneous moments of people with disabilities going about their daily lives at the Liming Center, was shown in a gallery in Beijing and in international media.

The sisters actively promote a connection between the community and the Liming Family centers. They recruit local families to be "supportive parents." For 300 yuan (about $40 per month), a family "adopts" one of the residents at the Liming Center.

"Sometimes they come to visit, sometimes they take our patients to their house," said Mi. "We want to make a family that is there to support them for an emotional perspective."

She said that adoptive families relish the bonds they create with Liming residents, inviting them for holidays and weddings, staying in touch over the years.

They also match "supportive parents" with families of children with disabilities, to help give them extra support and enable the children to live at home.

Administrative mission

The St. Therese sisters are known as a congregation that specializes in organizational development. Part of their mission is advising other religious congregations on vision planning and running effective chapter meetings. But their expertise also extends to helping to administrate local institutions.

"We have organized more than 30 institutions [involved in disability work] to engage with each other across China," said Mi. "The Chinese government institutions have invited us to help their centers run better, and we work with a Taiwanese institute to create good standards for these institutions."

Some institutes in the network "are run by religious sisters; some are private," Mi added. "We realized our mission is to lead other institutes to develop at the management or professional level."

Originally, the Liming centers were run only by sisters, but eventually they realized that hiring experienced laypeople for administrative positions helped the organization run more efficiently. Mi said that, at the beginning, there were some clashes in leadership style between the sisters and the laypeople, some of whom are not Catholic. "We're still on our way to seeking the best management," she said.

The Liming Family was also able to forge a connection with the local government, a big step for a religious congregation where the government is often hostile or suspicious regarding religious groups.

"Each time before the spring New Year, we would go to the government and ask for support, but we were always ignored," said Mi. "They thought we did useless things and wasted money."

"The government does things according to their policy," she explained. "Years ago, there was no policy to support disability or religion. As time passed, we have pushed for policies to change."

Slowly, that policy has changed and, with it, the government's attitude. The government now has its own therapy and occupational centers for people with disabilities, though there isn't enough space for all of the children and adults who need those services.

According to civil data from 2013, there were 878 nongovernmental orphanages in China, such as the Liming Family, serving 9,294 abandoned children. More than half of the orphanages — 583 — were run by religious people, including Catholic sisters and Buddhist monks.

Previously, the Chinese government's refusal to recognize or assist these private orphanages resulted in many challenges. A major difficulty was registering abandoned children for the Chinese equivalent of a social security number, since the nongovernmental orphanages were unrecognized.

Starting last year, the government agreed to pay a small portion of the Liming Family's budget. While the amount the first year was small, the sisters said, it was a huge step in the recognition of the congregation's work and service to the community.

Zhang, the vice director of the therapy center in Gaoyi, credits the government support with its emphasis on connecting the residents of the Liming Family to the wider community. "This [speakers bureau] is so people will pay more attention to them but also so we have some connection with the government," she said. "We are trying to inspire the government to take care of these kids."

"The support is complicated and sensitive because of religion," she added. The government has also started its own welfare houses for children with disabilities.

A morning (movie) star

Zhang stops for a moment to scroll through her cellphone, until she stops at a video of one of the beloved Liming Center success stories: 4-year-old Tian Chen Xing, whose name means "morning star."

"He had very serious cerebral palsy, and he came here when he was 3 months old," said Niu, the director of the Gaoyi center.

The cellphone video of Chen Xing's first steps with his leg braces raced through the sisters' messaging groups, and they send each other dozens of pictures and videos of Chen Xing via WeChat, China's popular messaging service. During Mass, Chen Xing gets passed from sister to sister, as he makes faces to get them to smile and gets covered in kisses and affection.

"He's made a huge development in speech and walking, and, without therapy, it wouldn't have been possible," said Niu.

"It's a very successful case," she added. "He's like a movie star in the congregation."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]