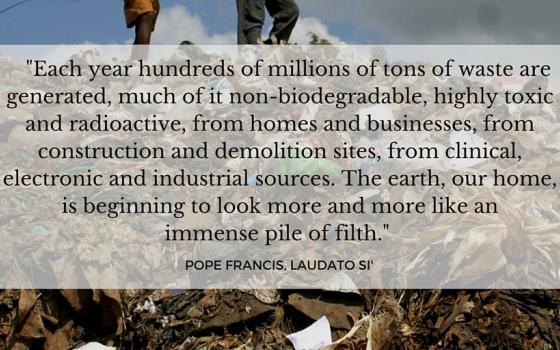

Global Sisters Report is publishing a special series about how trash is managed in the world and how sisters are helping people affected by landfills. We start this project to mark the one-year anniversary of Pope Francis' encyclical, Laudato Si', about climate change, pollution and waste, which warns that: "The Earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth."

______

Sarika Dhamke was only 10 when the onus of looking after her seven-member family fell on her shoulders.

Her mother, the family's only breadwinner, had fallen ill, and Dhamke, being the eldest of three girls and two boys, had to take up the challenge.

The only apparent option for the illiterate, untrained girl was to join hordes of slum children who scavenged in the streets and landfills of Indore, a central Indian city of 1.5 million.

That was 12 years ago. Now Dhamke owns a three-room house in the same slum where she grew up in a tiny hut. A year ago, she married a truck driver; one of her younger sisters also was married, and the youngest siblings now attend school.

"What I am today is because of the sisters. They helped me save money and get a proper price for the waste materials I collected. They also trained me to lead a better life," Dhamke told Global Sisters Report as she squatted with her siblings in the front room of her 350-square-foot house.

Dhamke is among some 2,000 women in the Indore slum who credit Catholic nuns for the drastic changes in their lives.

The nuns work in the Jan Vikas (People's Development) Society, a church social service center in the commercial capital of Madhya Pradesh state. Dhamke recalls that, after her mother fell ill, she was forced to do something to feed the family. "My father was an alcoholic who never bothered about us," she says.

She had seen her mother collecting discarded items — plastics, metals, wires, glass bottles, paper — from roadsides, dumping grounds and other places. "Since waste collection does not require any skill and training, I started to do it," she says.

Unlike other waste pickers who wear tattered and soiled clothes, Dhamke dresses in clean, colorful saris with a matching blouse whenever she is off work. "The nuns also taught me the value of cleanliness and hygiene," explains the woman, who works independently.

The Jan Vikas Society labors among 10,000 people living in 35 of the 559 officially recognized shantytowns of Indore. It was started by Divine Word Fr. George Payattikattu in 2001 as part of his order's decision to serve the people living poorly in urban areas. Before that, the Divine Word priests had mostly worked in rural areas.

Payattikattu says their field studies convinced them that waste pickers in the city were mostly women who were exploited in various ways. "Even though they are doing a great service to society by clearing waste, they are treated as outcasts or untouchables," the priest laments.

Because priests had limitations in working with women in India's conservative society, Payattikattu approached Augustinian Sr. Julia Thundathil, a social worker, to help him in the mission. The nun began to interact with the waste pickers soon after she joined the church center in May 2002.

"When I first met them, they were very hesitant to even talk as they suspected we were there for converting them," recalls Thundathil.

Madhya Pradesh is one of the Indian states that consider religious conversion a criminal offense.

As her traditional approach to influence the waste pickers failed, she decided to become one of them. For over a year she worked as a scavenger, going to the waste pile and "doing everything that they did," Thundathil told GSR. She learned that waste pickers leave home around 4 a.m., collect garbage until noon and then go sell it in a scrap shop.

"I also followed their schedule, just like one of them," she says. Asked how she coped with the stench and filth of landfills, she says, "When you work for Christ, no difficulty can stop you from achieving your target," adding, "I became a rag picker for Christ and help his people."

She says street dogs and pigs often attack the women while they are working. The workers also suffer needle pricks and other dangers because people do not separate wastes before dumping them into garbage bins.

Thundathil says her experience as a scrap collector helped her gain "immense insight" into the women's lives.

Their main problem is their alcoholic husbands, who physically assault them, she says. "The husbands do not do any work and cling to their wives like leeches," the nun says, and adds, "It was really disgusting and painful to listen to their stories."

When Thundathil started working among waste pickers, they earned an average 30 to 50 rupees a day (U.S. 65 cents to $1.10). The husbands commonly snatched up half the money for drinks, and any resistance met with a thrashing.

Moreover, the scrap dealers underpaid the women, who were illiterate.

Payattikattu said Thundathil took the initiative to start a financial self-help group and a cooperative society for the women in 2004. The members included waste pickers and domestic workers who lived in the slums.

"We wanted to bring value to their life, bringing qualitative changes in their lives," the priest says.

With the help of the nuns, the center educated the women about separating the garbage according to its commercial value. This practice helped improve their earnings.

"There are 16 varieties of plastics, and their prices vary from 2 rupees to 20 rupees a kilogram," the priest explains.

Enterprising women such as Dhamke now earn more than 300 rupees (about $4.50) a day. Thundathil says the women found the cooperative society to be a big boon for them as they began to save up to 5 rupees from each day's income. This helped them avoid moneylenders, who charged exorbitant interest for loans. The society charged only 1 percent interest for money the women borrowed whenever they were in need.

All this allayed the slum dwellers' misgivings about the Catholic priests and nuns. "They started believing that we were there for their welfare and not conversion," Thundathil says.

Dhamke says she managed to build her house with a loan from the cooperative society and other savings.

To circumvent swindling by dealers, the church center opened two garbage shops for the women. But it had to close them after scrap dealers complained, Payattikattu recalls. However, the initiative to train the women to sort better prompted the scrap dealers to pay them three or four times more than before.

The center has pressed civic authorities to issue identification cards to waste pickers to protect them from unwanted harassment from police and local people. Divine Word Fr. Roy Thomas, director of Jan Vikas, says the police first suspect the slum dwellers whenever a theft takes place in the city.

After ensuring economic stability for the women waste pickers, the center began training them in health and hygiene and conducted awareness classes on HIV/AIDS.

For young people, the center offers English language classes, introduction to computer use, tailoring and embroidery, and several other courses.

In 2015, the center turned its attention to those working in landfill areas in the city. Thomas says women working in landfills do not come in direct contact with the waste pickers who work on demarcated roads. The work is the same, but it's easier not to have to roam the city streets looking for waste and risking unwanted attention, he says.

More than 590,000 people live in 114,000 slum households in Indore, according to the 2011 national census. Every day the city generates about 700 tons of waste, which is transported by trucks and dumped at the landfill at the city's outskirts.

Sr. Sushila Toppo, an Our Lady of the Garden sister, began working among women in landfill areas a year ago. "They are more comfortable than those on the roadside, in terms of work and earning," the 38-year-old nun told GSR. Toppo and Thomas estimate the landfill covers about 500 acres of land in Indore.

One of the women working in the landfill area is Pinki Goswami, a widow. "I opted for this work after my husband's death three years ago," says the 25-year-old mother of three.

She is happy now because she can earn more and without reporting to a boss. She had first worked as a domestic. "I had struggled to support my family as I could hardly earn even 2,000 rupees a month," she recalls. Now, she takes home an average 500 rupees a day ($7.45).

Toppo also organizes occasional medical check-ups camps for Goswami and other women, taking care not to disturb their work.

Another worker, Maya Prajapati, says scavenging in landfills is safe for widows like her. "We get paid for the work we do. We are accountable to ourselves. We have work all the time in all the seasons," says the 30-year-old mother who wants to send her two children to school.

Toppo says Prajapati is an exception. "Most rag pickers don't send their children to school as most of them are illiterate." The prime objective of most women is to eke out a living for their family. "They are not bothered about anything else," she says.

However, the nuns want the women and their children to join skill development and awareness programs to better their lives.

Toppo's efforts seem to have succeeded. Kiran Gadwal, a waster picker at the landfill, said the nun visits them often and treats them with compassion.

"The landfill is a place where nobody likes to come. It is dirty and stinking. But the sister keeps visiting us and is very warm and friendly," says the 30-year-old mother of five children. She says people always looked down on them.

Kaushalya Bakawala, another landfill worker, says before joining Jan Vikas they had led a primitive life with no knowledge about the world outside the garbage cans. "But now things have changed," she says.

The 46-year-old mother of five says their association with the church center has emboldened them to oppose those trying to oppress them.

"I was very shy before coming into contact with the nuns, but now I do not fear to go to the police station or meet local leaders," she says.

[Saji Thomas is a freelance journalist based in Bhopal, a central Indian city. He has worked for several mainstream newspapers such as The Times of India. This article is part of a collaboration between GSR and Matters India, a news portal started in March 2013 to focus on religious and social issues in India.]