Passionist Sr. María Angélica Agorta visits with a woman in her home in Villa Hidalgo, Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Photo: GSR/Soli Salgado)

At 35 years old, Gaby* is a mother of 13, a grandmother, and a runaway convict.

Of her 13 children, eight have been put into foster homes over the years as a result of her and her partner's drug dealing, for which they were ultimately imprisoned several years ago. After she got pregnant while detained, she negotiated a brief release in November 2020 to give birth while under house arrest and leave her baby at home in her Buenos Aires villa, or urban shantytown.

But while she was out of prison, Gaby destroyed her ankle monitor, opting to live like a fugitive and gamble life behind bars if she's found.

For the Passionist Sisters who regularly meet women like Gaby in Villa Hidalgo, navigating the art of accompaniment can feel like a minefield, learning through trial and error how to initiate meaningful conversations that eventually yield trusting relationships.

Passionist Sr. Florencia Buruchaga, right, visits with a woman in her home in Villa Hidalgo outside Buenos Aires, Argentina. (Photo: GSR/Soli Salgado)

"In other villas, the abuse a woman suffers is more visible" in the form of bruises from domestic violence, Sr. Florencia Buruchaga said. "But in Villa Hidalgo, their suffering is more private, more invisible."

The trust between Sr. María Angélica Algorta and Buruchaga and the residents of the villa began as most Argentine relationships do: chatting while drinking mate, a traditional herbal tea.

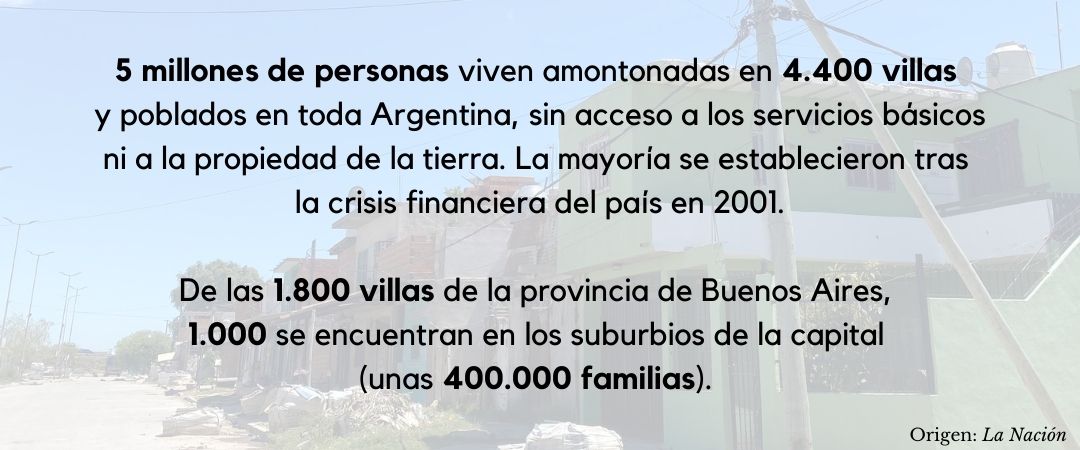

Entering the villas of Buenos Aires as an unaccompanied outsider is commonly discouraged; for most of the population, driving past the stack of tin houses peeping above the highway is the closest they may ever get.

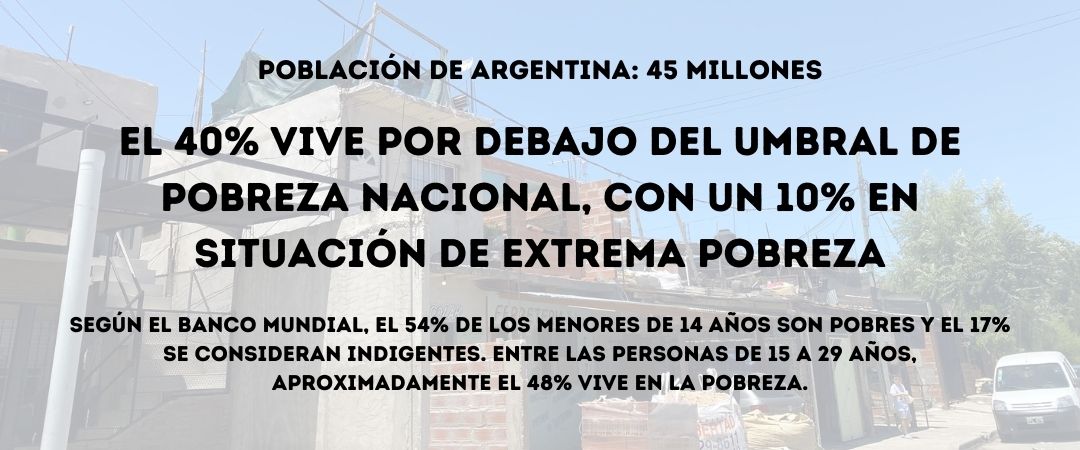

(Graphic: GSR/Soli Salgado)

The ticket into Villa Hidalgo for Algorta and Buruchaga (who live in the suburb of San Martín, a five-minute drive from the villa) was a young woman who sought their help: Her cousin was about to attempt suicide by throwing herself onto the nearby train tracks, and she wanted the sisters to counsel her. Since that incident, the sisters continued returning to the villa with the woman, walking the unpaved roads together and stopping for conversations as they slowly became familiar faces.

While Buruchaga and Algorta are the only two ministering in Villa Hidalgo, their fellow sisters throughout the city carry on similar work in their nearby villas.

"We are Passionist because we accompany the passion of men and women, especially the most neglected," Buruchaga said.

"We believe that, today, the most neglected are the women of the villa."

Passionist Srs. María Angélica Agorta, left, and Florencia Buruchaga have spent their entire religious lives living with people on the margins but began ministering to the residents of Villa Hidalgo outside Buenos Aires, Argentina, in February 2021. (Photo: GSR/Soli Salgado)

A space just for villa women

The sisters find inspiration in Fr. José María di Paola, a friend of Pope Francis who's known as "Padre Pepe" throughout Argentina, and his ministry, the Homes of Christ. Padre Pepe and his team have established spaces throughout the country over the last 20 years with a focus on addiction or those affected by it. The ministry welcomes young people from the streets with hopes of helping them address their issues, usually related to abuse, drugs or crime, and "preparing them to return to the streets — that is, their environment — and hopefully transform their families, too," Buruchaga said.

But of Argentina's roughly 150 Homes of Christ, few, if any, are dedicated solely to women.

"Behind a woman, there is always a child," and therefore women are more "complex" to help, Buruchaga said. "She never moves alone, whereas when a man wants to do a treatment, he can just go and do it. But the woman doesn't have that possibility because she has to take care of the children, the school, the house, the husband. She's relegated."

A family gathers outside their home in Villa Hidalgo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, on a late summer morning in January. (Photo: GSR/Soli Salgado)

In February 2021, the sisters, linked with Padre Pepe's team and resources, aimed to create a space similar to a Home of Christ for the women of the villa: Project Dignity. They would need help from local women to get started.

When they knocked on the door of the villa's Caacupé Chapel, the eventual site of their community space, the sisters met Olga Barreto. They asked her if she and the women needed help and accompaniment.

"Sí, mucho," Barreto remembers telling them.

Barreto moved to Buenos Aires from Asuncíón, Paraguay, in 1999 "with only the clothes on my back," she said, along with her then-toddler daughter and her partner at the time. "We were looking for a better life. There just wasn't work [in Paraguay], no way to advance."

Barreto is the emblem of a villa woman: The Paraguayan immigrant works as a domestic maid, is married to a builder and lives with two of her three children (ages 12, 14 and 24) in a small house.

"The villa needs a lot of companionship because so many women live badly, both economically and emotionally from abuse and violence," she said, adding that local children also become victims of violence, drugs and alcohol.

Three days a week, Barreto volunteers with two other women in the backroom of the chapel to hand out food and snacks to the children of Hidalgo and nearby villas, creating a space where kids can play, draw, sing and pray.

"Here, they have food and milk, but they also find peace where they know they'll be cared for," she said.

Before the sisters appeared at the chapel door to ask how they could help, "we felt very alone," Barreto said. "Now, we're supported in every sense": The sisters help them acquire food, offer spiritual sustenance, and oversee the construction of the chapel's communal space.

"The women now realize they're not alone, that there are people who are invested in their well-being, that someone is interested in what happens to them, that they're not invisible, that there are people who are aware of what's going on in their lives," Barreto said. "It gives them hope."

'This system does not allow one to grow as a person'

Though engaging with individuals is important in renewing the women's sense of dignity, the Passionist Sisters say the issue is systemic, as Argentina's welfare system has perpetuated generational poverty by not giving people who live in poverty any incentive to work.

Buruchaga and Algorta said those in the villas tend to fall in one of two categories: immigrants from Paraguay or Bolivia, most of whom arrive motivated to find work and pay, and Argentine families who have lived in poverty for multiple generations, many of whom have never known a family member to hold a job because they have long depended on substantial government checks.

(Imagen de GSR/Soli Salgado)

"If you talk to some people in confidence and ask them how much they earn with all their welfare checks, they earn much more than a person who works an official job eight hours a day," Buruchaga said, noting that this also creates resentment among the struggling middle class. "Federal assistance essentially deteriorates motivation to work."

That mentality is cyclical, the sisters said, and therein lies the injustice.

"This system does not allow one to grow as a person," Algorta said. "It doesn't respect their dignity because a system that respects a person's dignity would provide education, decent work." Instead, children from the villa's elementary schools can barely read, and high school graduates achieve elementary standards, in some cases "not even enough education to become a cashier."

The sisters, therefore, were intentional in not making their presence about handouts; rather, through the process of conversation, those they minister to come to appreciate the dignity of work on their own.

Then there's the pervasiveness of drugs: Algorta and Buruchaga estimate that for every 10 houses in Villa Hidalgo, eight sell drugs: crack, cocaine, nevado (marijuana laced with cocaine), and paco (a combination of crack residue, baking soda, and sometimes glass and rat poison).

"Here, drugs are a given," Buruchaga said.

But most resort to dealing drugs "because it's easy money, and they have no other option," she said. "They don't realize how hard it is to get out, that there's always a cost to getting involved."

Barreto agreed, saying most people "get involved in drugs out of necessity and from a place of pain."

One of Project Dignity's increasingly popular resources is Susana Orlandi, a clinical psychologist with experience working in prisons. The sisters recruited her to make weekly trips to the villa, where she hosts individual 30-minute sessions pro bono in the chapel's backroom.

Domestic violence, sexual abuse, malnutrition, and other conflicts in the home are typically the issues Orlandi hears from the women, she said.

"They've opened up a lot over time," Orlandi said, so much so that she recently increased her visits to twice a week so she can see more women, who learn about her through word of mouth.

"One of my ideas [for Project Dignity] is to create a women's group so they can support and listen to each other in group therapy," Orlandi said. Though the women come to her with different problems, "feeling alone" is at the heart of their concerns, she said.

Advertisement

"The differences I do notice with my private patients are the resources and tools they lack to advance their life and better themselves," Orlandi said, citing their economic dependence, the culture, and lack of education. "The problems may be the same, but the solutions are harder to come by."

Still, just having a space where they can feel heard is invaluable, she said. Working with women, "the effects are like a waterfall on their children and grandchildren."

Barreto said she dreams of greater outreach in the community and hopes they can "build a bigger team" to be able to do more throughout the villa, especially for the children who lack good role models.

"To change the lives [of those in the villa] — especially in just a year — is hard," Barreto said. "It takes time, work, therapy. They need help to learn, to feel that they're capable. But if there's accompaniment and interest in them, then little by little, they can achieve more. It's hard to solve everything at once, but we can make their load lighter."

For their part, the sisters hope to one day sell their home in neighboring San Martín and move to the villa to be closer with the poor "not just economically," Buruchaga said. "But poor in dignity."

*Global Sisters Report is not using Gaby's last name to protect her privacy.