Sisters of St. Casimir of Chicago and Lithuania on a July 2016 visit. From left: Sr. Jone Sofija Budryte of the Lithuania community with her memoir; Sr. Margaret Petcavage of the Chicago community; Sr. Birute Semenaite, who lives with Budryte; and Sr. Virginia Gapsis of the Chicago community. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

Sr. Regina Dubickas had every reason to go to Lithuania before 1992. Her parents fled the country in 1945 to escape the Nazi occupation of World War II, and some relatives still lived there. She grew up speaking Lithuanian, steeped in the country's culture. She even joined a religious community, the Chicago-based Sisters of St. Casimir, with strong ties to the old country.

For 100 years, the Chicago congregation and the Sisters of St. Casimir in Lithuania have stayed close despite distance, Soviet repression and the fact that for decades, the congregation's existence in Lithuania was illegal and operated only underground.

In those decades, some Sisters of St. Casimir did travel from the United States to Lithuania and came back with stories of communist repression, bugged hotel rooms and restrictions on whom they could visit and where they could travel. But not Dubickas.

"I would hear those stories and say, 'I'm never going to go when it's like that,' " Dubickas said.

Sr. Regina Dubickas speaks at an Aug. 25, 2018, blessing of the legacy room of the Sisters of St. Casimir of Chicago's museum. To her right is Sr. Margaret Petcavage, vice postulator for the sainthood cause of Mother Maria Kaupas, who founded the community. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

Finally, with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Lithuania regained its independence, and freedom was restored. In 1992, Dubickas celebrated her silver jubilee as a Sister of St. Casimir and was allowed to ask for a trip as a jubilee gift. She wanted to go to Lithuania.

"It was very personal, very intimate. It was a pilgrimage for me," Dubickas said. "I don't have words to describe my emotion as the plane landed."

An undercover community

Though the U.S.-based sisters look to Lithuania as their roots, their congregation was actually founded first.

Venerable Mother Maria Kaupas traveled to the United States in 1897 with her brother, a priest, to serve as his housekeeper. There, she met Catholic sisters for the first time — the few sisters living in Lithuania were contemplative — and decided she wanted to join a U.S. congregation. Instead, Lithuanian American clergy asked her to form a new community to serve Lithuanian immigrants.

On Aug. 29, 1907, the congregation was founded in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and named in honor of Lithuania's patron saint. In 1911, it moved to Chicago, which had a large concentration of Lithuanian immigrants and would be a more central location for the sisters' ministries.

In Lithuania at that time, the country's occupation by czarist Russia was fading as its leaders dealt with World War I and a socialist revolution, and in 1916, the bishops asked Kaupas to establish her congregation there. She arrived in 1920 with four sisters, and the government gave them the 17th-century baroque monastery of Mount Pacis, today known as Pazaislis, outside of Kaunas.

A view from the Pazaislis Monastery's central domed church belltower, which is surrounded by additional buildings that form several courtyards. In the distance is the Kaunas Reservoir along the Neman River. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

The Baltic nation's short-lived independence began in 1918 and ended in 1940, when the Soviets took over. Aside from a three-year Nazi occupation during World War II, it would be part of the Soviet bloc for the next five decades.

The Soviet Union tried to eliminate existing religion and prevent future religious beliefs. Religious property was confiscated; Pazaislis became first an archive, then a psychiatric hospital, then an art gallery. Believers were harassed or imprisoned, and atheism was taught in schools.

"The sisters were told to get out of Pazaislis, so they disbanded," Dubickas said. "Some fled by twos and threes and got apartments. They had to take off their habits and any sign of their faith."

Sr. Margaret Petcavage, a member of the Chicago congregation and the vice postulator for Kaupas' cause for sainthood, said there were 25 or 30 Sisters of St. Casimir in Lithuania at the time.

"They were told they had three days to pack up and leave," Petcavage said. "They had to find places to live and get jobs. They did get jobs in schools, but as soon as [the schools] found out they were nuns, they lost their jobs."

At least 12 sisters fled Lithuania entirely, escaping to the West. And yet, the little community survived.

Sisters gather in the dining hall in Pazaislis in July 2018. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

Petcavage said four or five sisters would get an apartment where they could live together in a sort of convent. She would later visit one that was considered the novitiate and had a hidden room in the attic where sisters made their vows.

"It was all undercover. ... They had their own code," Petcavage said. "So religious life continued."

But not without risks.

"They would never tell the superior where they were going so if they were investigated, she couldn't be tortured because she didn't know anything," Petcavage said.

When sisters were caught, they were imprisoned. The first two superiors after Kaupas were each jailed for five years.

Sr. Edita Sicaite, a Sister of St. Casimir in Lithuania, was born in 1972 and grew up under Soviet rule. She entered the congregation in 1996 and is now the principal of the Jesuit high school in Vilnius.

Sr. Edita Sicaite of the Sisters of St. Casimir of Lithuania, left, and Daina Cyvas, communications coordinator for the Sisters of St. Casimir of Chicago, met in Vilnius, Lithuania, on Sept. 22, 2018, during Pope Francis' visit to Lithuania. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

"I'm a child of the Soviet times," Sicaite told Global Sisters Report on a Zoom call with translation help from Daina Cyvas, the communications coordinator for the sisters in Chicago. "I had the grace of living with the sisters who lived through the Soviet oppression, so I had firsthand accounts of what it was like."

Sicaite said Lithuanians would speak in a sort of code where words had dual meanings in case the government was eavesdropping.

"The harshest times were in the '60s and '70s, then, little by little, the sisters from America would visit," she said. "But those meetings and experiences were not in the open. They were closed, and they kept guard."

The American sisters would visit the relatives of the Lithuanian sisters, who would then just happen to visit those same relatives while the Americans were there.

Sicaite said the sisters held secret retreats. They hid the actual number of those gathered by hanging white linen bedsheets to dry in the backyard then walking between the sheets. Anyone watching would only see six or seven women, not the 30 who were actually there.

"They had such strong faith that conquered the fear," she said. "That was the faith miracle."

Sicaite knew Kaupas' cousins when they were alive, and they would tell her how they would search rooms for government listening devices, sometimes finding as many as 10 in one house.

"I lived with two sisters who used to go back," Dubickas said. "You were allowed to go, but only under tight restrictions. You could only visit certain cities. Your families had to come visit you at the hotel, where the rooms were bugged. You couldn't go to their homes. Some wanted to visit cemeteries to see the graves of relatives who had died while they were gone but were told no."

Sisters of St. Casimir of Lithuania are buried at the cemetery on the grounds of the main Pazaislis compound in Kaunas, Lithuania. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

And though visitors could not bring religious items into Lithuania, the sisters traveling there would sneak them in, mixing rosaries in with other jewelry. They would also sew money into the hems of their clothes to bring to the Lithuanian sisters.

"I brought them rosaries and medals, and they oohed and aahed over them, but they were in no rush to take them," Petcavage said. "Eventually, they took them, but they certainly weren't going to be wearing them. Their faith and their religion was in their heart."

In the 1980s, one American sister went to a cemetery even though it was forbidden.

"She went with her family to her mother's grave and got caught and arrested," Petcavage said. "It's a good thing she was an American citizen so they couldn't really do anything to her. She gave them a mouthful."

The American sisters would bring or send money and, after Lithuania's independence, the Chicago-based sisters raised about $250,000 to help the Lithuanian sisters restore the monastery, which was in shambles.

A tour group looks up at the ceiling and frescoes, painted by Michelangelo Palloni, in the Pazaislis church in a room next to the central dome. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

Finally, after 52 years of oppression, the sisters were free to openly practice their faith.

"They had their old habits," Petcavage said. "Lord knows where they hid them."

Sisters cut from the same cloth

Dubickas' parents fled Lithuania in March 1945, in the final months of the war. They put some valuables in a trunk and buried it near their home, thinking they would return after the war, then packed the wagon with their belongings.

"They just kept going west until they got to Germany," she said.

Dubickas was born in a German refugee camp in 1946. Four years later, the family found a sponsor in Springfield, Illinois, and moved there. Nine months later, they settled in East St. Louis, Illinois.

"I grew up Lithuanian: speaking the language, doing the dances," Dubickas, now the community's superior, said. "Our church was Lithuanian."

Dubickas knew she wanted to enter religious life after high school, but she wasn't sure which congregation to join. She and her mother took a Greyhound bus to Chicago and visited the Sisters of St. Casimir because of their Lithuanian heritage, and Dubickas immediately felt at home. She entered the community in 1964.

Over the years, seven or eight sisters escaped from Lithuania and made it to the United States, joining the sisters in Chicago. Because they had been part of the underground Catholic community back home, they knew the Lithuanian families of the U.S. sisters and would bring news.

Advertisement

Petcavage's father had fled Lithuania at the start of World War I to avoid automatic conscription into the Russian army, eventually settling in Pennsylvania. His three older brothers had already fled.

"What a sacrifice families made so their boys could survive," she said.

Petcavage grew up in Scranton, and though not much Lithuanian was spoken at home, the family was part of a Lithuanian parish, and the children attended a Lithuanian school. Joining a religious congregation with strong Lithuanian ties made perfect sense to her.

Now, the congregation in the United States is down to 43 sisters, most of whom live in a retirement village. The motherhouse is owned by Catholic Charities. But the ties between Chicago and Lithuania are as strong as ever.

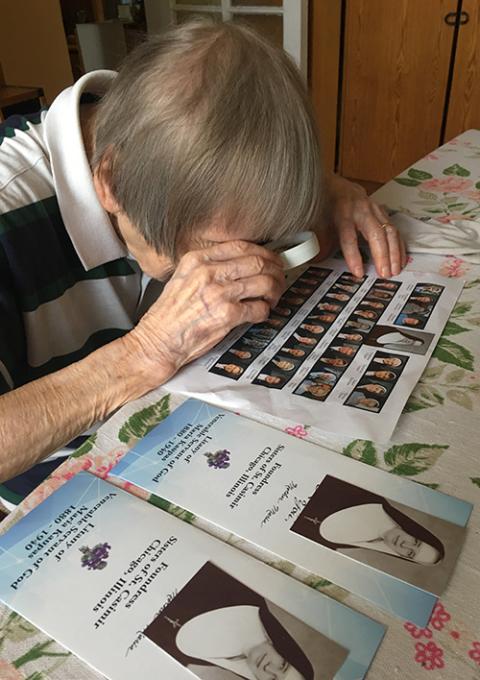

Sr. Jone Sofija Budryte looks at a photo of the Sisters of St. Casimir of Chicago in her kitchen in Vilnius, Lithuania. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Casimir)

"The foundation is the same," Sicaite said. "It's the roots. Their foundress, the prayers, their spirituality — it's all the same. So even if you've been apart 10 years, you feel like it's been just a day. Meeting the sisters from America, it was like you already knew them."

Dubickas has traveled to Lithuania several times since the early '90s, with many of the early visits aimed at helping the sisters there get the congregation up and running after 50 years of suppression.

On one of those visits, her cousins took her to the place where her parents' house had been. It had been destroyed during the war, and neighbors had dug up the trunk full of valuables they had buried. They were simple farmers, so the "valuables" had been things like good winter coats and household items.

"My mother did not go with me," Dubickas said. "She said, 'If my mother were still alive, I would go. But without her, it would be very hard for me.' Many people go back, but she didn't."

Her mother had told her that their farm had a hill that overlooked a lake and that she would often sit there and take in the view.

"When I was there, I had a few minutes alone, and I went and sat down by the water like she used to," Dubickas said. "Someone took a picture of me there. I had it framed and put up in my room."

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]