Three main factors in recent years have combined to depress enrollment at many Philadelphia-area Catholic colleges, particularly the smaller ones, like Immaculata University.

They are:

- Fewer parochial schools, once a reliable source of students for Catholic colleges

- Ever-climbing tuition and residence costs

- Students opting for less expensive schools or community college to avoid long-term debt

In July, Immaculata is taking a step that is both historically significant and perhaps important to the school's long-term prospects: bringing in a president who was instrumental in helping another Catholic university find a firmer financial footing. She also happens to be the school's first president who is not a Catholic sister or priest.

For its part, Immaculata trimmed its staff late last year and cut tuition rates by almost a quarter for the 2017-18 year in a move to attract new students. Indeed, the enrollment office reports its figure has stabilized in the last two years and is beginning to grow.

On July 1, the school started by the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary will welcome Barbara Lettiere, a 1972 alumna with extensive experience in the worlds of business and finance.

Leadership at Immaculata, now situated amid a bustling, well-trafficked suburb that has grown up around it, passes from the hands of Sr. R. Patricia Fadden to Lettiere, currently chief financial officer of Trinity Washington University and a member of the Immaculata Board of Trustees.

Like many of Immaculata's original students, the new president was the first person in her family to attend college, she said in a recent telephone interview.

The Trenton, New Jersey, native, who attended the now-closed Cathedral High School, recalled the impression that the Immaculata Sisters made on her during her first visit. "I was impressed by the caring of the sisters. It seems to be that they were most interested in my ultimate success and would do anything to ensure [it]. If you went to Immaculata, you were going to learn whether you wanted to or not."

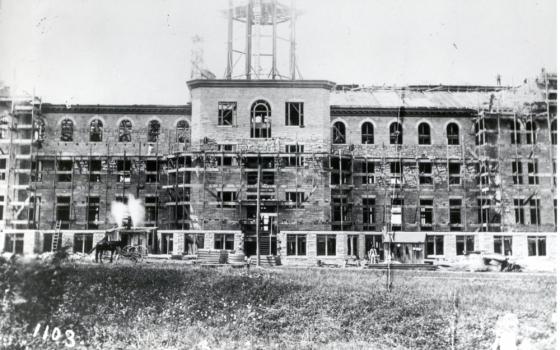

A presence in the Philadelphia suburbs since the later years of the 19th century, the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters have been committed to teaching since their founding in Michigan in 1845, says Sr. Anne Burton, the school archivist.

"From the beginning, we were educators, established to educate those children who needed one," she said from her office in the library, surrounded by glass-enclosed cases brimming with pictures and mementos that document the pathway from women's high school to coed university.

Many of the children they served in the early years of the 20th century were the daughters of immigrants interested in being equipped (the school offered business courses) to go out and earn a living, says Burton. Drawn by dint of founder Mother Camilla's persuasive vision for women's education, professors from Villanova University and other local colleges would make the trek to bucolic Chester County to teach sisters interested in getting a college degree in the evenings, returning home by bus the next morning, Burton says.

"I love it that Mother Camilla had that vision and that business acumen," said Burton. It was Mother Camilla Maloney who purchased the farmland on which the school that became Immaculata was built.

As it prepared for the transition to "lay" leadership, Immaculata did what other sister-founded colleges have done: created a position that would ensure that the order's charism would endure. That position, vice president for mission and ministry, is held by Sr. Mary Henrich, a Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and theology professor. Twenty-four colleges out of 104 sister-founded schools are still currently led by religious, 20 of them women.

Over the past year, Henrich has held several mission-focused meetings with faculty and administration throughout the school, she says. "My challenge this year was to get everyone talking about it, finding ways to articulate and promote the conversation," says Henrich, a former elementary school principal.

Though she didn't rule out the possibility of there being a future president who is a sister, says Henrich: "I just think now there wasn't a sister who felt that she had the expertise," adding that contemporary college presidents require a grounding in business as well as in fundraising and marketing.

The new president applauds the actions of the Immaculata community. "It was a very smart move on the part of the sisters to introduce this position on the university campus," says Lettiere, noting that a few years ago, the university also had changed its bylaws to allow a non-religious person to be head of the board of trustees and president. As president, Lettiere will no longer serve on the board of trustees, according to the university communications office.

From one college to another

As the recent CFO of Trinity Washington University, the new president is no stranger to grappling with the choices necessary for smaller colleges to survive. Lettiere says she recognizes the challenges that face her and Immaculata, including navigating regulations, competition for students, and the perception by some that the cost of a degree may outweigh its value. Many American college graduates, she added, take on substantial student loan debt, leading them and others to ask whether the degree was worth the expense.

Lettiere was praised by Trinity's president, Patricia McGuire, for practicing a "fiscal discipline" that enabled that university to build up financial reserves and to set the stage for rising enrollment. "Barbara Lettiere's considerable financial and managerial expertise from the corporate world turned out to be precisely what Trinity needed," McGuire said in a 2012 address to the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

McGuire credited Lettiere with modernizing Trinity's business management "from the outmoded practices of the old Catholic institution run largely on prayer, hope and the authority of 'sister says.' … Trinity gets a lot of press attention for the changes in our student body and academic programs. But as the saying goes, 'no margin, no mission,' and a great chief financial officer taught me and the institution, itself, how to build margin so that we could advance our mission."

An Immaculata donor (one of the buildings on campus is named in honor of her mother, Lillian Lettiere), Lettiere doesn't seem overly concerned about the transition ahead. "The sisters have done a very good job of preparing the institution for the advent of a laywoman. Being an alum solidifies in people's minds that I have only one goal in mind, which is the success of Immaculata."

She's more concerned, she says, about the uncertain future of many liberal arts colleges. "Higher education is under siege from several different forces, including government regulation and competition, not to mention what I consider to be the devaluation of a college education." She credits the Immaculate Heart community with the acumen to embrace coeducation at a time when enrollments were declining in 2005.

But Lettiere is impressed with the commitment demonstrated by the sisters. "Many colleges call themselves Catholic, and I'm sure they are, but the number of sisters and prevalence in the community is nowhere near that here."

As evidence of that commitment, she cites that Immaculate Heart Sisters have made financial pledges to the ongoing and prior capital campaigns.

Immaculata still has a relatively large community of women religious, with 37 faculty and staff residing at Gillet Hall on campus, 50 living across the street from the university in the Villa Maria House of Studies, including two novices and two postulants, 189 in the retirement residence Camilla Hall, and 37 in Pacis Hall, a residence for the nursing staff.

Today's students

Conversations with students suggest that the community of sisters conveys its commitment to social justice, diversity, the value of a liberal arts education and hospitality to students from the first time they set foot on the campus.

"I mainly see [the charism] manifested in how communal the school is," says Sarah Pasternak, a senior education major. "We just have each other's back. It really feels like home. It's not something you can describe. I tell my friends that you just have to experience it."

Sisters she met as a freshman will stop her while she's walking to class and ask her how her student teaching is going, or engage parents in friendly conversation, she says, adding that she hopes the new president will continue that "open relationship with every student on campus."

Now an admissions counselor at Immaculata, 2015 graduate Owen Logue underlines the same point. "The Sister Servants are a very welcoming group, and that makes Immaculata what it is," he says, adding that a lot of the sisters he had as teachers, particularly a professor of biology, had a "huge influence on my academic life."

Many students at the school also experience the sisters' mission as they participate in the numerous service and campus opportunities available to them, he adds. In addition to sponsoring service trips abroad, students can volunteer to work in Philadelphia and nearby Coatesville, an economically disadvantaged, once prosperous steel-mill town.

As chair of the Department of Health and Human Sciences who has been on the faculty for almost 30 years, Barbara Gallagher has become well acquainted with many sisters as colleagues and friends. "People talk about the IHM charism. It's not something you can put your finger on, but you know that it's there — a very strong sense of community and love that I still feel today."

Although the numbers of sisters on campus has declined in recent years, she says, their "work ethic" is remarkable, and their devotion to the school consistently evident. "I've never been in a situation where I didn't feel that."

That focus on faith is amply applied at Immaculata, where there are numerous options for exercising personal spirituality, service to others and public worship, says outgoing President Fadden in an email. "Departments are asked to develop at least one instructional outcome that supports Catholic identity and mission through the Catholic intellectual tradition or Catholic social teaching," she writes.

Immaculata became a university in 2002. It's noted in athletic circles for winning the first three national women's basketball championships, its story featured in the 2011 film "The Mighty Macs." The school enrolls about 900 traditional undergraduates, 600 adult undergraduates and more than 1,000 graduate students, almost one-quarter of whom are minority students.

Pasternak, who graduates this spring, expresses no doubt that her time at Immaculata has been well worth the investment. Over the course of the past four years, she says, "I've been forced to see other people's perspectives and my eyes have been opened to different ways of collaborating and understanding [them]. As a woman entering the real world, I feel that I've been changed for the better … the school has almost trained me to be a good person."

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist for Lancaster Newspapers, Inc., as well as a freelance writer.]

Editor's note, from the Global Sisters Report "Frequently Asked Questions About Sisters" page: "Because sisters are not ordained, they are considered part of the laity, not the clergy and therefore are not part of the hierarchical structure of the church." In common language, the term "lay" is often used to distinguish non-consecrated members of the church from both women and men religious.

Related - Sisters who blazed trails in higher education preserve heritage, charisms of Catholic universities