John Mwanamuke leans on his machete and wipes the sweat from his brow. Although it’s not quite 9 a.m., it’s already hot, since Western Zambia is the driest and lowest part of the country, where the shady forests of central Zambia begin to flirt with the Kalahari Desert in Namibia.

Mwanamuke’s energetic slashing of the scraggly weeds belies his 75 years of age, as he works to clear the area for an interdenominational prayer circle. Mwanamuke, the secretary of the local Catholic church, is just one of dozens of local volunteers building a new spiritual center called the Garden of Oneness in the middle of rural Zambia, founded by Presentation Sr. Teresita “Terry” Abraham.

“This is a place of prayer,” says Mwanamuke, as he looked across the peaceful garden slowly taking shape. “If I have a complaint that I want to put before the Lord, it’s a place where I can pray silently or with my family.”

With this garden, he added, villagers are reconnecting with their roots. “[Our ancestors] used to pray underneath trees, even before we were Christian,” he said. With this spiritual center, Abraham is “reminding us of what past we had, so we do not forget,” Mwanamuke explained. “Our past is of much importance. We use these traditions through God so we can come together in love.”

In their spirituality as Presentation sisters, Abraham said, includes belief in the sacredness of the earth and universe, “which is the spirituality of communion, with God, with one another, and with all of creation. We feel at the heart of every piece of creation is the spirit of God breathing,” she said.

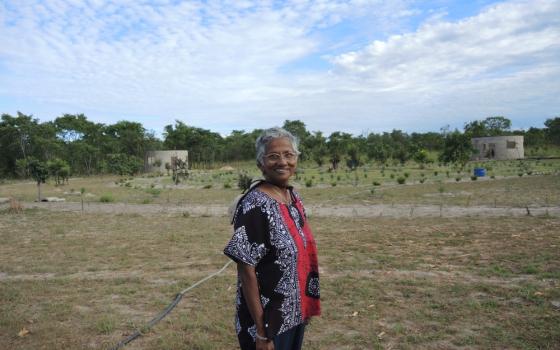

Abraham is originally from Kerala, India, and had worked in Zambia for 14 years as a missionary. Then she left to serve on the leadership team in the Presentation Sisters administrative center in Ireland for 13 years and returned to Zambia in 2014. She came back wanting to harness that charism (or ideology) of the ecology of spirituality and to work on a project of the spirituality of oneness. She started floating the idea about making a spiritual center deeply connected to ecology and the environment among her fellow sisters and the community of Kaoma, an agricultural town in the sparsely settled western part of Zambia.

“People took to it like fish to water,” said Abraham. “It’s so much a part of their own lives. People are so close to nature, so they’re very close to God.”

Abraham and the Presentation Sisters purchased land in September about 22 miles (35 km) outside the town and are now in the process of building and landscaping the property as an eco-spiritual retreat and education center.

Across Africa and Zambia especially, trees are under dire threat as they are pillaged to make charcoal for cooking. Impoverished, isolated farmers struggling with lack of rain are chopping down the trees to sell for charcoal, without replanting new ones.

But in the peaceful quiet of these 20 acres in rural Zambia, trees are hallowed and respected sovereigns of the land. Because the land was privately owned, the villagers did not harvest the trees for charcoal there. Soon after Abraham purchased the land, she invited the elders of the community to walk through the entire parcel.

“They identified one big strong tree they call the ‘mubanga tree,’ which means ‘strong tree,’ as a place to honor the ancestors,” explained Abraham. “They created a sacred space around this tree. The whole heart of spirituality is that God and our ancestors are journeying with us, always supporting us and sustaining us. They are with us all the time. We are never alone.”

When the community of Namilangi retraces the Stations of the Cross, they have found trees to illustrate each stop of Jesus on his way to the crucifixion. In one corner of the property, one tree supports another tree, representing the station where Simon supports Jesus.

When prayer moved out from under the trees into ornate churches and cathedrals, something was lost, Abraham believes.

“Church as an institution became like a rubric full of rules and doctrines, but here we can just come and have the Eucharist simply under a tree,” she said. “[Trees] hold something of that fabulous spirit that was always there, that harmony in all of our cultures that got damaged in industrialization. We can reclaim peace and harmony on us and in our relationship with creation and the creator.”

The Easter season is an especially poignant time to celebrate ecology, Abraham continued. The Paschal mystery – the story of birth, death and rebirth – is replayed thousands of time across the garden as the growth cycle renews each year.

African spirituality is closely related to nature and the idea of oneness. “Ubuntu,” an ancient Bantu word that means “I am because we are” or “oneness,” is a central tenet. Former South African president Nelson Mandela used the idea of Ubuntu to inspire climate change activists to unite together for the common good.

In Zambia, Abraham wants to transform her small bit of land into a haven of Ubuntu and a protected environmental area where generations to come can connect to their roots. Locals have come out in droves to volunteer, taking ownership of the idea of an eco-spirituality center.

“It’s a memory place, really,” explained George C. Marite, 75, the treasurer of the local church and a retired bricklayer who frequently volunteers to help landscape the garden. “For me, the story of oneness here, this is the place of remembering what our grandfathers and grandmothers did. There’s the mubanga tree – there’s so many trees! Even though we weren’t there during our ancestors’ time, the sisters are reminding us what happened long ago.”

“We’re not just volunteering to assist the sisters, we want to develop in spirit also so that our children can also learn about what is here,” added Mwanamuke, as he and Marite cleared underbrush for a section of the garden. Part of connecting to ancestral identity is created in a conservation area that will show what natural bush looked like in this region, before all of the trees were decimated. “When we die, our children can come up with stories about us and this place,” Mwanamuke said.

The eco-spirituality center is still under construction but will eventually have four African-style round houses with thatched roofs, one in each of the four directions. To the east will be the House of Light, with educational and resource materials. To the south will be the House of Story, utilizing the African tradition of storytelling and Jesus’s stories and parables to learn about environmentally friendly techniques for farming, composting and building. To the west will be the House of Compassion, which will focus on natural healing techniques like massage, acupuncture, aromatherapy, reflexology and herbal treatments. To the north, the House of Grace will be the house of silence, solitude, prayer and meditation. About 15 acres will be left wild, with walking paths crisscrossing the property.

All of the houses are built with a special interlocking brick that is not much more expensive than a regular brick but uses just a fraction of the cement. Orphans involved in another project run by Presentation Sisters in Kaoma are making them.

Although the construction is not yet finished, a feeling of peace already envelops the property. Abraham’s words carry visitors on a spiritual journey as she paints her vision for the center with lavender and succulent plants.

“Take anything in creation, and you’ll find that no two leaves, no two human beings are the same, not even two twins are the same,” Abraham explained in her steady, musical voice as she walked the spiral path ringed with lavender and aloe vera that will represent the story of creation.

“No two grains of sand are the same. So you see diversity everywhere – we’re all different, even every piece of hair is different. And yet, there’s an essence to everything. When I work with the farmers in the village, I ask the farmers who plant the maize, ‘Do you ever teach the little maizies how to grow?’ No, there’s an inner wisdom that it knows how to grow and grow to its fullness. We diminish that growth because we damage the earth and we damage all other life species. We do it because we want to dominate, and we do it mindlessly. We must wake up to that wisdom, because this wisdom is everything.”

The Garden of Oneness, however, has many logistical hurdles to overcome before it is complete. Materials and cost of living are approximately the same in Zambia as Europe, and Abraham estimates the entire project will cost $100,000. The community builds piecemeal as they raise money from donors abroad and small donations from the villagers, but they are still tens of thousands of dollars short.

The project’s location also makes it difficult to be self-sustainable. Abraham envisions that there may be accommodations on the property, which could be rented for spiritual retreats or seminars. But Kaoma is a five-hour drive from the capital of Lusaka. Though there is a tar road in good condition from Lusaka, the location is much too far to be convenient for international visitors or NGOs working in other parts of the country.

Abraham bristles at the suggestion that the Garden of Oneness would be more geared towards visitors from outside rather than the local villagers who built it and took ownership of the idea. However, since most residents are subsistence farmers barely making ends meet, they will not be able to pay for the services planned for the eco-spirituality center, including natural healing. “In the center itself, we don’t have anything that provides,” she said. “It will create a culture of communion, of supporting one another.”

She has applied for grants from international organizations, but has not received any. “I can understand that if you’re looking after orphans, or if it’s an economic project, it’s easier to get funds,” she acknowledged. In an area that is so impoverished, where so many children go hungry and there are so few schools, it seems strange to dedicate so much money to a spirituality center rather than a school or a clinic.

But Abraham believes that when sisters step in to provide the services the government should be offering, it allows the government to shirk their responsibility. And she asks a simple question. “Just because they are poor, don’t they deserve to explore their spirituality?”

“At first people wondered, ‘Why give the sisters this place?’” Marite, the church treasurer, said. “But it is good. Now people come to draw water for their families,” from a well the sisters drilled, he explained. Others are learning about sustainable farming and the importance of planting new trees when they cut one down for firewood. “Visitors who are coming, even those who aren’t Catholic, they come and see. . . . What a development in our area!”

As the brick walls grow higher on the houses on the four directions of the compass, Abraham and the volunteers survey the site with satisfaction: a place of peace, which they built through sheer will.

“It’s been an adventure of faith,” admits Abraham. Even though her project doesn’t help in the traditional service capacities that sisters usually undertake in Africa, she believes that the Garden of Oneness will be a place of inspiration.

“There’s an awakening happening, the whole world is waking up to that spirit of oneness,” she said. “On one side, there is so much about Al Qaeda and the wars and violence, and that’s the news that we get on every channel. Who tells the story of the good things that happen? Humanity is waking up to this oneness, waking up to something more profound, something deep that gives meaning and purpose to our lives.”

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]