Community leader Germán Gracianos, right, speaks at the gravesite of Édinson David* on March 23, 2025. The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, Colombia, began its 28th anniversary celebration with a pilgrimage to the gravesites of two members killed in 2024. (Tracy L. Barnett)

As the late afternoon sun dipped behind the forested hills of this tiny Colombian community, a handful of campesinos gathered below the iron archway over the dirt road. COMUNIDAD DE PAZ, read the bold letters. Community of Peace.

People had already begun to arrive in the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó for the big 28th anniversary celebration on March 23, 2025. But first, there was another, much darker anniversary to commemorate. Community members and their supporters had just returned from an arduous three-day pilgrimage to La Esperanza — the remote rural hamlet where Nallely Sepúlveda and Édinson David, two beloved community members, were killed the year before. Their deaths were one more chapter in a long and brutal history of violence.

The grief was palpable, etched in faces and carried in silence. But alongside the sorrow, there was laughter. Children ran gleefully amid the dogs and chickens. Their parents greeted guests with smiles and embraces. In this place, joy and mourning are not opposites — they walk hand in hand.

The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó was born in 1997, during a time when the Colombian countryside was gripped by violence. Paramilitaries, guerrillas and state forces vied for control, and civilians paid the price. In the decadeslong conflict, more than 9.8 million Colombians have been impacted by the violence, and more than a quarter million killed — most of them rural farmers like the community members. Amid that chaos, a group of campesinos made a radical decision: to renounce all armed protection, to reject collaboration with any faction, and to remain on their land, no matter what it cost them, as a neutral, nonviolent civilian community.

Although the war officially ended with the 2016 peace accord, the violence did not. As guerrilla forces withdrew from rural territories, paramilitary groups — created by ranchers, landowners, business leaders, and the state itself, and trained by the military — took control. These groups, long linked to drug trafficking networks and other underground economies, consolidated their dominance in resource-rich and strategically located lands like the one occupied by the community.

More than 300 Peace Community members have been killed, and impunity has remained largely the norm. Yet the community endures, rooted in collective memory, food sovereignty and spiritual resistance.

Community members hold a sign during their procession to the gravesites of members killed in 2024. It reads: "28 Years: Building a community fighting in defense of life and territory — resistance in the midst of the absence of justice, seeing how our rights are violated, seeing fathers, mothers, children, brothers and sisters and companions in the struggle fall assassinated, we continue resisting from memory, demanding justice for our loved ones." (Tracy L. Barnett)

In a ceremony livestreamed from the presidential palace, Colombian President Gustavo Petro issued a formal state apology on June 5 to the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó for the massacres, threats and persecution it suffered at the hands of state actors.

He praised the community's commitment to peace, sovereignty and civil disarmament, calling it a model that could inspire conflict zones around the world. The act fulfilled a binding agreement with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and marked an unprecedented public reckoning by the Colombian government.

Members of the Peace Community were present at the ceremony, standing alongside human rights defenders, international observers, diplomats, and civil society representatives when Petro delivered his apology in Bogotá's Casa de Nariño, as Fellowship of Reconciliation Peace Presence reported.

Sr. Mariela Beltrán is pictured on March 23, 2025, at the grave of Nallely Sepúlveda during the memorial service for Sepúlveda and Édinson David, two community members killed in 2024 in La Esperanza. Peace Community members and supporters traveled to La Esperanza to commemorate the anniversary of their deaths. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Soon after the Peace Community's inception, international observers began to maintain a presence through groups like Peace Brigades International, Operazione Colomba, Fellowship of Reconciliation and Tamera Ecovillage's Institute for Global Peace. The international presence helps keep the violence at bay, though with the community dispersed as it is through a vast network of rural hamlets, it's impossible to be everywhere at once.

"For every attempt to eliminate them, they've responded," said Sr. Mariela Beltrán, a Catholic sister who has walked with the community for more than two decades. "And their answer is to live each day in the sovereign way of life they've chosen."

The entrance to the Peace Community is pictured, with a contingent waiting for a bus in San José de Apartadó, Colombia. (Tracy L. Barnett)

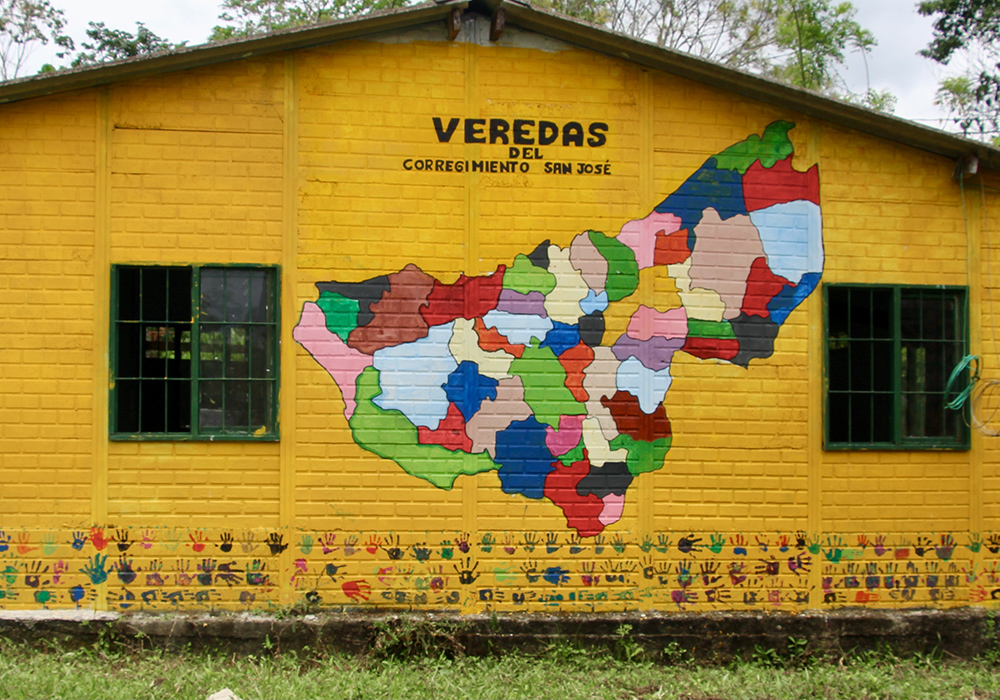

A living map of resistance

Beltrán, dressed in old jeans and a simple T-shirt like the campesinos she lives with, greets friends warmly with every step. As she leads visitors down the narrow dirt path that weaves between simple wooden homes and a central monument to memory, she traces out a living map of resistance.

At the heart of the community is a memorial dome, a ceremonial home to their many dead, rows of faces gazing down from the walls. In front of the building, forming the silhouette of the Serranía de Abibe mountain range, rises a constellation of brightly painted stones, each inscribed with the name of a slain community member.

"The idea," she said, "is that none of them ever be forgotten. We keep them alive in many ways." A series of murals, painted by community members with the help of local artists, encircles the memorial enclosure, telling the story of forced displacement and massacres, but also of celebration, tradition and the abundance they have been able to bring forth on this fertile land.

"Every space here carries memory," said Beltrán. "Nothing is placed by accident. The center of this community is its memory — and its love for those who are gone." At the edge of the memorial park, just a few paces from the community meeting space, is an ossuary with the human remains of community leaders and children who have been killed. There rests the grave of Eduar Lancheros, a lay missionary and beloved mentor. His words are still a guidepost: "Convertir el dolor en esperanza. No permitir que el dolor te destruya." — "Transform pain into hope. Do not allow it to destroy you."

Beltrán, who belongs to the Order of the Company of Mary Our Lady, has accompanied the community through some of its most painful chapters. Her presence as an educator, pastoral guide and witness has been a quiet but vital form of spiritual resistance — one rooted not in doctrine, but in deep listening and shared struggle.

Beltrán first came to San José de Apartadó in 2001, when she was serving as the principal of a public school. "The community asked for someone to accompany them, especially to teach the children," she told Global Sisters Report. "I arranged for a temporary replacement at my school and traveled to the village of La Unión," one of the 32 hamlets that, along with this base of San Josecito, make up the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó.

Just a few weeks after her arrival, soldiers entered the area wearing hoods and set fire to the village of San José de Apartadó. That night, fearing the worst, the people of La Unión fled to the mountains — Beltrán among them. The evacuation took place just eight months after the La Unión massacre, when six people were killed by paramilitaries — a still vivid memory.

But what stayed with Beltrán — and what ultimately convinced her to stay — was the strength.

"Seeing how they assume the pain, how they live it with fortitude, how there is no bitterness but rather hope," she said, "all that speaks of people with great mental strength, with much love for the land."

"For every attempt to eliminate them, they've responded," said Sr. Mariela Beltrán, a Catholic sister who has accompanied the Peace Community for more than two decades. "And their answer is to live each day in the sovereign way of life they've chosen." Beltrán is pictured at the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, Colombia. (Tracy L. Barnett)

In February 2005, something even more devastating occurred in the remote hamlets of Mulatos and La Resbalosa. Eight members of the community — including Luis Eduardo Guerra, his partner Beyanira, and their 11-year-old son, Deiner — were brutally tortured and killed by soldiers and paramilitaries while on their way to harvest cacao, the community's most important cash crop. The soldiers and paramilitaries then continued on to La Resbalosa, where they killed a family with two young children and a worker. Guerra was the community's liaison with the Colombian government — a beloved, high-profile leader who had traveled to Europe to seek support for the community.

Beltrán wasn't present at the time, but she understands the immense pain the community has experienced and has accompanied them as they've healed from this attack and so many others.

"That was perhaps the darkest moment," she said quietly. "We didn't know if the community could survive such a loss. But what I witnessed was how collective grief became a source of strength."

Advertisement

The keeper of memory

Brígida González's broad smile and lighthearted banter belie the pain she has carried for decades. The 73-year-old former labor organizer and community cofounder tosses her long silver braid over her shoulder and beckons visitors into her front room. Here she displays a gallery of folk art that began as a way of processing pain, then became her sustenance.

Each item has a story, some of which she relates on a tour through the exhibit, showing the colorful knitted handbags, the beaded jewelry, the watercolor paintings. "I don't need a psychologist because I am my own psychologist, through my artistic work," she said.

And then she moved to the Memory Wall. "This is my daughter," she said, pointing to a portrait. "They assassinated her on Dec. 26, 2005, in a massacre — an extrajudicial execution," she said quietly. "I thought I would collapse and never get up again, but I was able to stand up and continue resisting and fighting. Because it's not just her, it's all of us. And I know that she, despite being dead, between remembrance and memory, she continues living with me, she helps me too."

Brígida González of the Peace Community in San José de Apartadó, Colombia, is pictured with her Memory Wall in her home. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Elisena had just turned 15 when she was killed in her sleep, accused — without evidence — of joining the guerrilla. Brígida González lost her two sons, as well; one was disappeared and the other was killed. And three cousins, brothers and countless friends and colleagues. "It's almost a miracle that I'm still alive."

Now as the caretaker of the community's memory park, González keeps Elisena's memory alive along with those of hundreds of her friends and neighbors.

Standing at the center of the dome, she pauses for a moment of silence and looks around at the faces gazing down. "I don't know if you can feel it here, but there are moments when you walk in and you can feel their energy. That's how I know: We don't die completely — we die to be born, and we are born to die."

A territory under threat

The Peace Community sits on land of immense geostrategic and economic value — a vital corridor between Colombia's interior and the Caribbean, near the site of a new, state-of-the-art international port and above one of the country's largest coal deposits.

"The exploitation of coal needs a port, which is the port of Urabá," said Beltrán. "It needs roads and needs to have no one inside. This is why they attack the population — because they need the region empty to develop mining exploitation — which has not been able to proceed because the Peace Community offers resistance with another proposal for life and for work."

José Roviro López, now 37, was only 10 when the community was founded. Now a member of its eight-person governing council for the past decade, he faces constant death threats.

"These are 28 years where we've had to endure pain — I think more pain than joy," he said, thoughtfully tending strips of a freshly butchered cow drying over a fire. "At the same time, we have built something remarkable together."

He feels a deep pride for what they have been able to accomplish: an egalitarian society that includes children, youth and elders in the decision-making, an alternative education system, and an agricultural system that grants them autonomy and abundance.

"We are among the only communities that still exist that confront the government, the paramilitaries, the guerrillas — whoever it may be — to claim the right, above all, to be in the territory and to live," said López.

That resistance has endured much longer than anyone thought it would.

"Ask anyone — they'll tell you," said Beltrán. "The Peace Community knows it has no future. Every day is a victory — just being a Peace Community," she said. "The important thing is to continue with the project for as long as possible — and to raise awareness among the world, or as much of the world as possible, that we can't keep destroying the planet."

*This story has been updated to clarify a cutline.