(Unsplash/Mateus Campos Felipe)

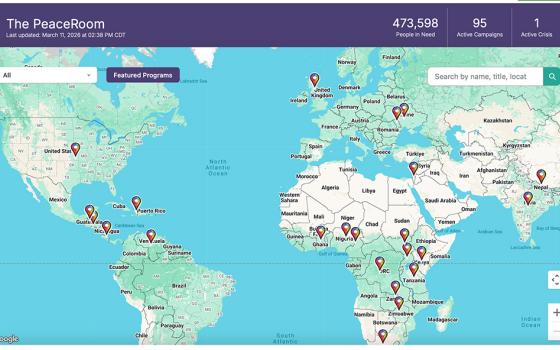

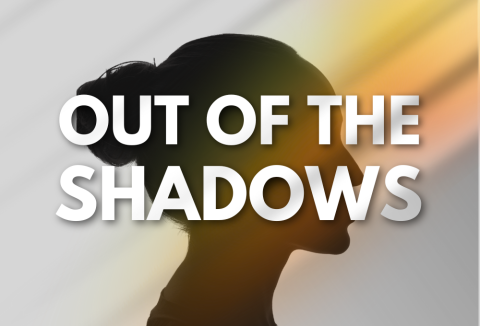

Editor's note: This story is part of Global Sisters Report's yearlong series, "Out of the Shadows: Confronting Violence Against Women," which will focus on the ways Catholic sisters are responding to this global phenomenon.

(GSR logo/Olivia Bardo)

Speaking about sexual abuse within the church is not an ideological matter or the result of external pressure. Above all, it is a profoundly Gospel-centered issue. It places us before the core of Jesus' message: the sacred dignity of every person, the protection of the most vulnerable, the truth that sets free, and the justice that heals. For this reason, the question many believers are asking today is neither superficial nor ill-intentioned, but honest and painful: Is the church truly seeking to combat sexual abuse, or is it trying to manage its consequences?

The church has spoken words, drafted documents, and created commissions and protocols. However, the existence of structures alone does not guarantee a culture of care. The issue is not whether organizations exist, but how they function, whom they listen to first, and what fruits they produce. "By their fruits you will know them" (Matthew 7:16) — not by the thoroughness of texts or the speed of statements.

'If the church truly wants to combat sexual abuse, it must cultivate a spirituality of listening: listening without defensiveness, without haste, without strategies of control.'

—Sr. Adriana Pérez

Many people who have reported abuse — especially when it involves ordained ministers or individuals in positions of power — describe experiences marked by silence, delay, lack of information, and, at times, a profound sense of abandonment. In some contexts, there even appears to be urgency to provide immediate, partial, or merely formal responses, as if the priority were closing the case, easing consciences, or simply "moving on." This creates in victims the painful impression that what is expected of them is compliance or patience rather than truth, justice and genuine reparation.

The Gospel does not propose quick answers meant to soothe consciences. Jesus never offered superficial relief. When he encountered human suffering, he stopped, listened, asked questions and touched the wound. "What do you want me to do for you?" (Mark 10:51), he asks the blind Bartimaeus. He does not presume, decide for him, or rush the process. Healing begins where the person is heard in their truth.

Within this context, the document Vos Estis Lux Mundi stands as a strong and necessary call. "You are the light of the world" (Matthew 5:14). Light does not conceal, protect shadows or negotiate with darkness. Light exposes, reveals and unsettles. Yet being light does not mean simply promulgating norms; it means allowing truth to illuminate even what wounds the church's own institutional image.

It is worth asking, then, whether Vos Estis Lux Mundi has truly been embraced as a path of conversion or whether, in some places, it has been reduced to formal compliance. The light of the Gospel cannot be applied selectively. "Nothing is concealed that will not be revealed, nor secret that will not be known" (Luke 12:2). These words directly challenge every form of cover-up, minimization or relativization of harm.

'Combating sexual abuse is not limited to sanctioning individual misconduct; it requires examining the power dynamics that made it possible.'

—Sr. Adriana Pérez

(Pixabay)

Combating sexual abuse is not limited to sanctioning individual misconduct; it requires examining the power dynamics that made it possible. Clericalism, repeatedly denounced by the magisterium, continues to be a real obstacle when it prevents listening to victims or questioning those who hold authority. Wherever power is protected instead of serving others, the Gospel becomes obscured. Jesus spoke clearly and forcefully: "Whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to stumble, it would be better for them if a millstone were hung around their neck" (Mark 9:42). There is no room for ambiguity in these words.

The effectiveness of commissions cannot be measured by the speed of their responses, but by the depth of accompaniment they provide. Victims do not need gestures meant to "satisfy" them, but transparent processes, clear information, reasonable timelines and the assurance that their testimony will not be questioned out of convenience. "The truth will set you free" (John 8:32), yet truth requires courage, especially when it carries institutional cost.

From a spiritual perspective, this crisis is also a call to conversion. Sexual abuse is a wound in the body of Christ, and every denied wound deepens. There is no healing without truth, nor reconciliation without justice. Authentic mercy is not indulgence without accountability; it is commitment to the dignity of the person who has been harmed. The prophet Isaiah expresses this forcefully: "Learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed" (Isaiah 1:17).

Advertisement

If the church truly wants to combat sexual abuse, it must cultivate a spirituality of listening: listening without defensiveness, without haste, without strategies of control. It must listen even when it hurts. God also speaks — and in a privileged way — in the cry of those who have been violated. "I have witnessed the affliction of my people, I have heard their cry" (Exodus 3:7), the Lord says. The question is whether we are willing to hear that cry today.

The church's credibility in this time does not rest on solemn statements, but on concrete gestures of coherence: in how it responds to those who report abuse, how long it takes to act, and whom it protects when the cost is high. There, it becomes clear whether the Gospel remains at the center or only a distant reference.

Being the light of the world means accepting that this light must also illuminate our shadows and trusting that only truth, even when painful, can open paths toward healing and hope.