The global problem of homelessness and affordable housing will soon get more attention at the United Nations, and an Irish sister who heads a U.N.-based advocacy group is becoming one of the major players in that effort.

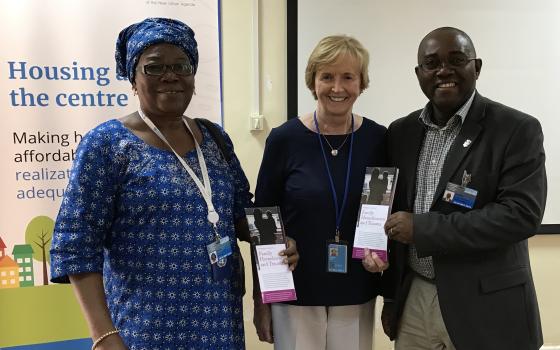

Daughter of Wisdom Sr. Jean Quinn, executive director of UNANIMA International, a coalition of Catholic congregations at the U.N. focused on concerns of women, children, migrants and the environment, was one of 15 "expert" participants who presented papers at a May 22-24 meeting in Nairobi, Kenya.

The meeting was part of preparations for the U.N. Commission for Social Development's 2020 priority theme of homelessness and affordable housing. The gathering sought "to deepen the understanding of complex inter-linkages between poverty, inequality, social exclusion and homelessness," UNANIMA said in a statement about Quinn's participation.

It is no surprise Quinn was selected as an expert. Prior to her appointment in 2017 at UNANIMA, Quinn headed Sophia Housing, a Dublin-based organization she founded that provides care and support for people who are homeless who also face challenges of mental illness and addiction.

Quinn's ties with Sophia Housing and her native Ireland continue: In April, UNANIMA, Sophia Housing and New York University announced they will launch a two-year global research study on family homelessness and trauma. The study will have a special focus on the experiences of women and children. Also participating will be nongovernmental groups that work with those who are homeless.

The U.N.'s taking up of the issue comes as it continues its 2030 agenda of 17 sustainable development goals of eliminating global poverty and other social ills.

Goal No. 11 does assert that U.N. member states should by 2030 "ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums." The U.N.'s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights also affirms housing as a human right.

But the global body has not yet mounted a head-on effort on homelessness and affordable housing, and there is, as of yet, no common international quantitative measurement of homelessness.

"The absence of an internationally agreed definition of homelessness hampers meaningful comparisons," Quinn said in the paper she delivered at the Nairobi meeting.

More broadly, Quinn noted that obtaining "an accurate picture of homelessness globally is challenging for several reasons." These include "variations in definitions. Homelessness can vary from simply the absence of adequate living accommodation to a lack of permanent residence that provides roots, security, identity and emotional well-being."

Definitions also vary across countries "because homelessness is culturally defined based on concepts such as adequate housing and security of tenure."

Still, what is known is serious: Estimates by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing dating back to 2005 say that "approximately 100 million people worldwide are without a place to live. Over 1 billion people are inadequately housed." Quinn said more recent figures used during the Nairobi meeting, culled from numbers by U.N. member states, indicate there are about 150 million homeless people in the world, about two percent of the world's population, and that 1.6 billion lack adequate housing.

Efforts to determine more exact numbers will continue, Quinn told GSR, noting that one of the themes of the Nairobi meeting was: "If you can't count it, you can't change it."

But in an interview following her return from Nairobi, Quinn acknowledged that the issue of homelessness and affordable housing at the moment is "not a priority" for U.N. member states, as governments view the problem as local.

But there may be another hurdle to clear: It's taboo.

"Sometimes governments are embarrassed to talk about homelessness," she said.

Yet the problem is global in nature, and of particular concern for Quinn and others is what she calls family homelessness affecting women and children, which is often invisible. By contrast, street homelessness, a phenomenon in which men tend to be more visible, has become the symbol of the problem.

"Women and children are often forgotten, and that's often because a woman won't bring a child to the street," she said. "It's often not visible with women and children."

Both street and family homelessness are serious problems, Quinn said, though in her paper she pointed out that family homelessness "is unfortunately a growing phenomenon around the world."

The gravity of the problem is such, she argued, that this is the moment for "a paradigm shift in how we perceive the problems of poverty and homelessness and that it is time for a revolution on the subject. We need urgently a paradigm shift away from the many abusive attitudes and beliefs that circulate around homelessness. We need to start this dialogue by viewing and treating homelessness as what it is: [as] human and civil rights issues."

Quinn said the issue deserves urgent attention by UNANIMA and sister congregations that do advocacy work at the United Nations. She said the question for her, looking ahead to U.N. discussions next year, is, "How do we raise our voices to be prophetic, to be honest, and calling homelessness for what it is?"

In her paper, Quinn cited a number of causes of homelessness, including a shortage of affordable housing and related financial speculation in housing that has caused housing costs to rise throughout the world. Other factors: lack of social protection systems, displacement from conflicts and natural disasters, ongoing poverty, and challenges related to mental illness, substance abuse and alcoholism.

Another critical problem, Quinn said in her paper, is domestic violence, "a wide-spread and deeply ingrained issue that has serious implications on women's health and well-being."

"Domestic violence," Quinn wrote, "is widely ignored and poorly understood. It is also a leading cause of homelessness for women and children. When women are caught in this situation and need to leave their homes, they not only suffer the physical and psychological consequences of losing their homes, their support systems are taken from them as well."

One participant at the U.N. meetings in Kenya compared homelessness to an "overflowing bathtub," Quinn said, requiring "turning off the tap." But you also have to deal with the immediate problem of not leaving water on the floor — and that means tending to immediate needs as well as long-term solutions, she said.

"The whole issue," she said, "is enormously complex. And it deserves our full attention."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is [email protected].]