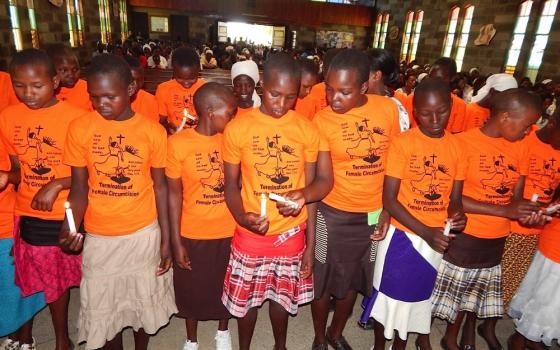

Eighty girls wearing orange shirts hold candles aloft at the St. Charles Lwanga Parish, the flames shining in their eyes. After a week of lectures and seminars, these 80 girls are announcing to their families, their church, and the world: We are the light that will shine across Kenya, we will not undergo female genital mutilation.

The girls, from villages northwest of Nairobi, are participating in a Christian Rite of Passage, an alternative to female genital mutilation organized by Sr. Ephigenia Gachiri. The Loreto sister has been crisscrossing the country in her bright yellow car for the past 16 years, bringing her message to the most remote corners of Kenya: God made you beautiful, don't ruin his creation with female circumcision.

But she soon realized that while it's important to educate parents, teachers, and the girls themselves about the dangers of the cutting, education is only half the battle. In order to completely stop the practice, there must be an alternative ceremony to help girls gain the cultural maturity that the FGM ceremony provides without the dangers of the actual procedure.

What is FGM?

According to the World Health Organization, female genital mutilation (also called female circumcision or female genital cutting) is defined as any procedure that alters female genital organs for non-medical reasons. This ranges from removing part of the clitoris, to removing part or all of the labia, to infibulation, which means sewing the vaginal opening together, only allowing for the passage of bodily fluid.

Cultural reasons for FGM include preserving a girl's virginity, controlling her sexuality so she will not cheat on her husband, and promoting characteristics like obedience and passivity.

More than 130 million girls and women alive today have undergone the ceremonial cutting in the 29 countries where it is practiced, mostly in Africa and parts of the Arab world. The World Health Organization reports that there are about 2 million to 3 million women who undergo the mutilation in Africa every year, or at least 6,000 per day.

In Kenya, 27 percent of women aged 15 to 49 have undergone FGM, according to the United Nations. The process usually takes place before a girl reaches puberty, though sometimes as early as 6 or 7 years old.

"When I started this work, I thought that I'd finish it in three years," said Gachiri on a sunny afternoon in Nairobi. "I thought the whole of Kenya would be converted in just three years. That's how fervent I was, and I was working day and night. . . . I thought, once I tell people [about the dangers], they won't do it, especially the women," she added.

At the feet of the circumcisers

When Gachiri first began working on this issue, she spent six months meeting every female circumciser that she could find in the Muranga district in Kenya's interior. She had appealed to bishops in numerous regions, but found the most support among those in Muranga, a region that begins northeast of Nairobi just as the urban sprawl of the capital region ends.

Once there, Gachiri, who has a Ph.D. in education, sat for hours on low wooden stools, listening to the traditions leading up to the cutting ceremony, the cultural rite of passage that marks the transition from girl to woman. She knew that she could not approach communities to talk about this centuries-old practice unless she understood the entire ceremony and its place within the tribal culture and traditions. After she slowly gained the trust of the women circumcisers, they enthusiastically shared their traditions with Gachiri. Some even gave her gifts of circumcising tools, convinced that she would be joining their sisterhood.

When she had enough material to write a book, Gachiri shifted from listening to activism. She secured permission from the village chiefs, church leaders and government authorities, and began visiting schools during the week, asking to speak with the girls. At first she visited three schools a day, for a two-hour session at each school, until exhaustion forced her to cut down to two schools per day. On the weekends, she'd visit churches, following a rural priest as he celebrated Mass at three or sometimes four different churches.

"I'd talk about how God created us, and how beautiful we are and how we spoil the body," Gachiri said. "Sometimes they would run away from the church when they heard what I was talking about. Some would leave so fast they'd forget their handbag and you'd see them stop at the door and have to come back to get it."

Deep roots

One of the major issues with eradicating FGM is that women can be more attached to the tradition than men, Gachiri found. There is an enormous amount of cultural importance placed on this rite of passage, which is believed to ready the girl for adulthood, motherhood and the rest of her life. Women who are attached to the ritual can view it as part of a celebration of sisterhood, Gachiri realized.

"Girls told us that they have to be circumcised because their ancestors are pleased by the blood that is spilled, and the ancestors will pray for them and bless them," she said. "If you are not circumcised, you will not have the protection of your ancestors, so you will be in danger," the girls told her.

Sometimes girls in tribes where FGM is practiced even demand to get cut. "They have different [derogatory] names in different communities that they call uncut girls," explained Gachiri. "They call you this name every time you drop a cup or when you can't light the fire or can't carry firewood. Every time you're told, 'this is because you're not circumcised,'" she said. "When you go to the river, you can't fetch water with the others. You have to wait until they have fetched the water and then maybe they've mixed it up with soil and mud so it's dirty. Then they all go up talking and laughing and you have to be the last one. Then you walk up alone. How do you survive?"

Even if a girl has not been cut before marriage, perhaps because she comes from a place where FGM is rare, she is still at risk if she marries into an area where FGM is more prevalent. "If you marry a man and you're not circumcised, none of his friends can come to your house and eat food," Gachiri explained. This complete isolation is difficult in rural areas where community support is essential. Even a woman who has given birth is not safe from genital mutilation. A husband's family can still conspire to cut an uncut woman, even after she has given birth to multiple children, because boys cannot be circumcised when they reach puberty unless their mothers are circumcised.

"You are treated like that until you ask for FGM yourself," said Gachiri. Girls sometimes ask for the ceremony because they want to emulate their mothers or older sisters.

"Children are so innocent," she added. "They ask me, 'Sister, will it grow again now that it is cut?'"

A sister on the road

After completing her research, Gachiri started traveling more extensively in Muranga. She visited schools then shifted her focus to adults through women's groups and church groups. She appealed to them to invite her for a lecture on the dangers of cutting, including a video she made detailing the medical issues of the unhygenic operation.

In the seminar, Gachiri or a medical expert explains that the immediate health dangers include tetanus, urinary retention and infection, fever, sepsis or blood poisoning, and hemorrhaging, which can lead to death. Long-term problems include recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections, infertility, fistula (a hole in the birth canal that leads to obstructed labor), complications during labor from scar tissue, formation of cysts, dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), anemia and death. She also speaks about the psychological problems and the conflicts the practice creates in a marriage.

Despite initial opposition, including cultural resistance in Kenya about discussing sexual matters in a public setting, this part of the message started getting through to the groups she visited.

"You reach a point where you have given the facts and they've accepted them," said Gachiri. "[FGM] looks bad and they agree. But what about the other mystical parts?"

Gachiri researched the spiritual aspect of the ceremony for her book Female Circumcision, published in 2000 by Pauline Sisters Publications. The book describes the cutting ceremony as part of a decade-long maturation process for girls, which integrates them into the community and the unique structure of extended families in African tribes.

In traditional settings, there are more than half a dozen celebration ceremonies associated with this maturation process that give the community opportunities to gather and pass knowledge down to the younger generation. The process also creates strong bonds with a girl's age mates who are going through the ceremony at the same time, and they solidify relationships with her extended family members, who each have specific roles to play in the ceremony. The process creates the position of a "sponsor" who nurtures her during the healing process after the ceremony and remains an important mentor during the rest of her life. All of these positive relationships are part of the social fabric of the tribe, but they are inextricably linked to female genital mutilation.

"The women said to me, 'You want our children to grow up like goats?'" Gachiri recalled. "'You know, goats are born and when they mature they give birth. They don't get married; when they are old they die. They have no process, no ceremonies. Do you want our children to be like this?'"

It took a few years of these seminars before Gachiri realized she couldn't just talk about the negative aspects of this rite of passage — she would have to provide an alternative. "They have to have a ritual, maybe not FGM, but something that tells the girl, 'You are now mature and prepares them for life,'" Gachiri said.

Shining the light in Njoro

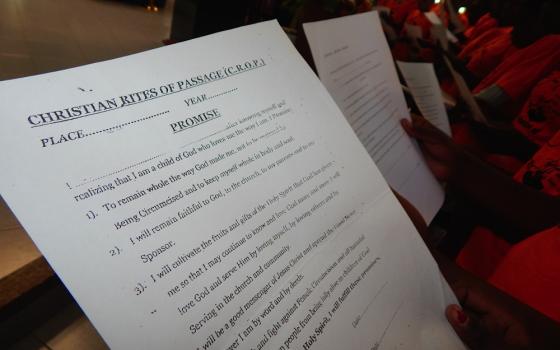

After brainstorming sessions with fellow professionals, including psychologists, religious leaders and social workers, Gachiri created an alternative rite of passage adapted for Christian adolescents, along with a workbook for girls and boys. She holds the Christian Rite of Passage, or CROP, ceremonies in August and December each year, during school vacations, which are the most popular times girls undergo FGM.

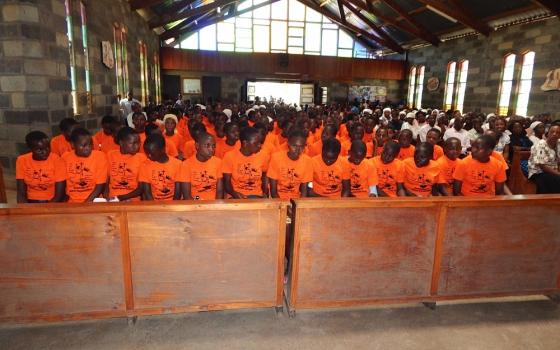

At the Njoro parish, 80 girls gathered in late August, 2015, for the weeklong seminar ending with the celebration Mass. "This time I had fewer girls even though I was expecting 200 to turn up," Gachiri said, as she was distributing orange T-shirts to the girls. "Last week in Gilgil I had 170 girls. Sometimes the parents change their mind at the last minute and do not send their girls to our seminar. Other times it is almost impossible for the girls to get here because of the rains and bad roads in very remote parts of the country."

The seminar involves 33 sessions on topics that offer psychological, emotional, mental and spiritual teachings to the girls, with an aim of giving them a smooth transition to adulthood.

There are also lectures on marriage, biological changes during adolescence, hygiene, nutrition, HIV/AIDS, and drug and alcohol abuse. Gachiri's extensive field research has enabled her to create seminars that capture the traditional teachings of a certain area combined with modern knowledge. She has trained a staff of 30 people to run these workshops, which are always held with the blessing of the local priest, pastor or village chief.

In Njoro, six other mentors joined Gachiri to teach the lectures. After seven days, the girls, most aged 13 to 16, celebrated their journey in a special graduation ceremony attended by their parents, friends and church community. The girls stood in front of the entire room and made a promise to themselves and to God, "to remain whole, the way God made me, and not to be maimed by being circumcised, to keep myself whole in the body and soul."

One graduate, Mary Wairimu, told GSR, "I took part in this program five years ago and it changed my life. I am here today for my younger sister's graduation. My mother and I encouraged her to come. Our parents are too shy to talk about issues around sex but Sister Ephigenia breaks that taboo."

Wairimu, now 24, is a nurse at one of the local hospitals. "I have seen the dangers of FGM where I work in the maternity wing, and I am glad my mother brought me to Sister Ephigenia instead. I talk to my neighbors and friends and discourage them from going for the cut," Wairimu added.

That dedication to spreading the message is exactly the intent that Gachiri hopes to promote.

At the celebration Mass that is part of every graduation ceremony, the girls are invited to the front of the congregation where they take a pinch of salt from the presiding priest.

"Jesus referred to his disciples as 'the salt of the earth,'" explained Gachiri. "My girls will be the ones to go forth and spread the good word about this Christian Rite of Passage."

The church service ends with the lighting of candles and raising them as a symbol that the girls are the light, just like Jesus the light of the world. They too will shine on and stand out from their peers.

"I underwent FGM myself in the '80s, I cannot lie to you that I didn't," said Anne Mweru, the mother of one of the graduates. "Back then, we didn't know about the dangers of FGM, but now we know. The other problem we had was the lack of an alternative. I am now a Christian and follow the ways of the Lord."

Her friend Martha Muthoni, 53, added that her own attitude did not change overnight. "Caroline is the last of my six daughters, and the only one to have escaped 'the cut,'" she said.

In November, when schools broke for the summer holidays, Gachiri ran three additional seminars for 550 girls. In one village, they only had enough food and accommodations for 167 girls, but 300 showed up. The lack of running water and money to buy additional food meant they were forced to turn away nearly 130 girls on the second day. “Turning children away after one night is very painful,” Gachiri wrote via email. But it also illustrates the extent to which communities are starting to embrace the seminars.

"This was my first time to be away from home," 15-year-old Eunice Mweru, the daughter of Anne Mweru, said at the August ceremony in Njoro. "I was more excited about being away, but now I am even happier because of everything I learned here."

A gradual change

Gachiri has noticed over the years working on this issue that there has been a shift. Part of that is due to a Kenyan law passed in 2011 making female genital mutilation illegal. This means that, on paper, if a girl does not want to go through it, she can go to the police. Technically, police have the authority to arrest anyone associated with the cutting, including the parents, the circumciser, a sponsoring mentor or the host of the ceremony. However, this rarely happens for a variety of reasons, including police incompetence or collusion between police and community leaders.

Making cutting illegal has now pushed it underground, meaning it is harder to stop, and often it is not accompanied by the traditional rituals and processes that place the ceremony within a larger cultural tradition.

Police involvement, though usually welcome, can also complicate the matter. "One time we heard of a place where 100 married women had been circumcised and some of them were still sick," said Gachiri. "Then when the police came, [the women] were taken to the forest to be hidden. What is going to happen with those women who are already sick and have no medication, and they're in the forest in the cold and the rain? Running like animals from the police? How do you feel?"

According to the U.N. statistics, prevalence of FGM has decreased by 16 percent in Kenya from 2003 to 2008, the latest year that comprehensive statistics are available. UNICEF estimates that Kenya is one of six African countries that have made significant steps and might be able to eliminate cutting by 2030.

Gachiri has also started to see results in her areas. There are many other NGOs working to stop FGM, such as actress Waris Dirie's Desert Flower Foundation and Compassion International. Since the law was passed in 2011, the national Kenyan media has started to report on instances where circumcisers were fined or arrested, or when girls died.

Gachiri sees this evolution herself at the beginning of the seminars that she runs for adults, when she asks women if they have been circumcised. "They used to stand up and say, 'Yes' with great joy and pride," she said. "They used to be very proud, but now, today, they are not very proud. Something has happened to the whole population."

The difference? Information is slowly seeping to the villages, and people are beginning to realize that the cutting ceremony is dangerous and harmful to the girls, she said. Getting the medical information out is the first step. The second step is combatting deeply held tribal beliefs, partly by offering an alternative rite of passage.

"You can't force it," said Gachiri. The answer, she explained, is education. "You can use education, because people are basically good — they don't want to harm their daughter for harm's sake. They thought [cutting] is good for the child and the community."

Gachiri's work is effective, but it is time-consuming and effects change only on a small scale. She is currently raising money to build a $60,000 "Termination of FGM" training center outside of Nairobi in hopes of reaching a larger audience across the country. It will also mean she can keep her little yellow car parked at the Loreto convent in Nairobi for longer than a few weeks at a time. "I'm getting tired," said the 71-year-old Gachiri, who recently celebrated her golden jubilee (50 years) as a sister.

In Njoro, Gachiri hands out certificates and serves cake to the girls and their families. This week, she and her staff have hopefully made a difference for 80 girls in this region. But there is so much ground to cover in Kenya alone. Despite her progress in the Muranga region and Masai areas south of Nairobi, Gachiri has yet to make any progress with the Kisii tribe. The Kisii have one of the highest rates of FGM, but their leaders refuse to meet with Gachiri.

"It is tough," Gachiri admitted. "But it needs to be someone with a passion and a vision. I will not tire. I will not stop."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel. Atieno Otieno is a freelance journalist based in Nairobi.]

Related story - One girl in Kenya finds a safe haven from FGM, and a future