Editor's note: Global Sisters Report is bringing a sharper focus to the plight of refugees through this special series, Seeking Refuge, which will follow the journeys refugees make. For more GSR coverage on migration around the world, click here.

______

For months, Dominican Sister of Peace Janice Thome has been thinking about what she'll do when the Garden City, Kansas, location of the International Rescue Committee closes this September.

For four years, the local IRC office has been a valued resource for the many refugees who end up in the small Midwestern meatpacking town. It's been a hub where newly resettled refugees could could find things like education and food and housing assistance. But come September, it will be one of dozens of casualties of President Donald Trump's new policies aimed at stifling refugee resettlement in the United States.

Last year, the Trump administration capped the number of refugees allowed to resettle in the United States at 45,000, the lowest number since the White House began capping admissions in 1980. Then, in February 2018, the State Department told agencies that any locations resettling fewer than 100 refugees per year — like the Garden City IRC office — would need to downsize or close.

In shuttering resettlement agencies, the Trump administration is echoing a political ethos that first began brewing in Kansas. In 2015, Republican Sam Brownback, then governor of Kansas, signed an executive order prohibiting state agencies — and any organization receiving grant money from the state — from helping Syrian refugees build their lives in Kansas.

At first, Brownback's move wasn't distinctive. Three days before, a group of gunmen and suicide bombers in Paris killed 130 people in six coordinated attacks. When a passport belonging to a Syrian refugee (later determined to be counterfeit) was found next to the body of one of the suicide bombers, it set off a maelstrom of anti-refugee rhetoric in the United States; on the day Brownback signed his executive order, 25 other governors announced their states would no longer accept refugees from Syria.

Then, in January 2016, Brownback expanded his original executive order to prevent state resources from being used to help refugees from any country come to the Sunflower State. Four months later, he withdrew the state from the federal refugee resettlement program, making Kansas the first state to do so for "security concerns." Texas, New Jersey and Maine would follow suit.

Brownback's policies didn't stop refugees from coming to Kansas — no governor has the legal authority to wall off his or her state — but it did lob the state into a moral battle over the its obligation to those seeking refugee in the U.S.

Sr. Esther Fangman, a Benedictine Sister of Mount St. Scholastica, served as a volunteer counselor for refugees in Kansas City, Kansas, for almost a decade before she was elected prioress of her community last summer. She said in the aftermath of Brownback's policies, her refugee clients reported an uptick in children being bullied in school and in adults encountering discrimination.

And then there was the violence. In October 2016, three men were arrested for plotting to bomb Somali refugees in Garden City. Then, in February 2017, a man shot and killed an Indian engineer in a Kansas City suburb after yelling at the engineer to "get out of my country."

"Because of what's happened in the [state] government the past two years, there is much more fear," Fangman said. "The dream of the United States is that you have a chance to make it here. Now, all of a sudden, that begins to shift. They begin to wonder: Will my children have a dream? Will they make it?"

Meanwhile, other Kansans have countered the violence and xenophobia with an outpouring of support for refugees. In the aftermath of Brownback's policies, Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas — the largest resettlement agency in the state, based in Kansas City — has seen an influx of volunteer requests from people who want refugees to know they are welcome in the state, said Rachel Pollock, director of the organization's refugee and immigration programs.

"It's honestly been challenging for us as a resettlement agency," she said. "It's a great problem to have, but we have more people wanting to engage than we know what to do with."

Pollock said the refugee aid community in Kansas has rallied to make up for the state's withdrawal from the federal resettlement program. Because it was necessary to have a central agency that could administer the federal money coming into Kansas for refugees, the IRC office in Wichita utilized a federal program that allows a private entity to step in for the state and created the Kansas Office for Refugees, known colloquially as KSOR.

And while the switch in partners has forced local agencies to quickly adopt a brand-new way of doing business — a challenge Pollock said is hard to put into words — she said there has been a silver lining. Refugees were never the state's sole focus, she said, and resettlement work was just one of many issues for which they partnered with outside agencies.

"But the Kansas Office for Refugees is dedicated to this work, and they specialize in the work." she said.

Welcome to the Sunflower State

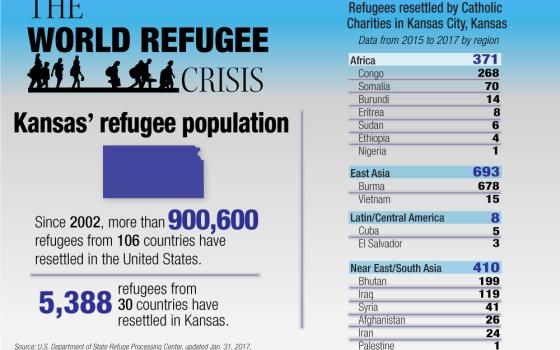

Kansas isn't a major primary resettlement destination. According to data from the U.S. State Department's Refugee Processing Center, about 5,300 refugees from 30 countries were resettled in Kansas between 2002 and 2015, most fleeing hunger and civil unrest in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or ethnic and religious persecution in Burma, also known as Myanmar. In comparison, California, the No. 1 resettlement destination in the U.S., resettled 3,100 refugees just in 2017.

About 75 percent of the refugees who come to Kansas are placed in the state's urban centers: Wichita and Kansas City, as well as suburbs part of Kansas City's metro area. A few are sent directly to rural Kansas, but many more move to agricultural locales like Garden City, Dodge City and Liberal after first being resettled elsewhere in the United States.

Thome, whose ministry of presence with refugees and the economically poor in Garden City is about to enter its 22nd year, said there's a pull toward secondary resettlement in rural Kansas because of the numerous meatpacking plants. Refugees are expected to secure employment within eight months of coming to the United States, she said, and while meatpacking is notoriously dangerous, it's one of the few jobs refugees can get quickly.

"It doesn't take much English to work at a packing plant," she said.

Albert Kyaw's first job in the United States was in 2007 at the SugarCreek Packing Company in Pittsburg, Kansas, a southeastern college town with a population of about 20,000. Kyaw had fled his native Burma in 2002 after he was arrested for reporting state labor abuses to the International Labor Organization. His wife and three kids joined him in a Thai refugee camp two years later before they were all resettled in Kansas.

Today, Kyaw, who was a teacher in Burma and Thailand, works as a Burmese translator for Garden City Public Schools. He likes Kansas and thinks it's a good place for refugees because "job availability is everywhere." In fact, he thinks the job market in Kansas is so favorable for refugees that they'll keep coming, if not as primary resettlers, then certainly as secondary migrants, no matter what the politicians in Topeka do.

"I think that doesn't matter much," he said, laughing.

Of course, Thome said, it's easy to be optimistic in Garden City. It's diverse — more than 22 percent of Garden City's residents are foreign-born, according to the latest Census data — and it's a welcoming community.

There are still Trump campaign flags waving atop local businesses, and the surrounding county voted decidedly for Brownback's re-election in 2014, but refugees and immigrants are integral to Garden City's economy. And that, Thome said, changes things. She's quick to point out that 2016's would-be bombers were not local; anyone in Garden City harboring anti-refugee sentiments would be smart enough to keep that information to themselves.

"But the attitude about refugees and immigrants here in our area is not the same throughout the state," she said.

Looking toward the future

The battle lines have been drawn, but it's hard to say where Kansas goes next. Brownback left the state in January to become Trump's ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, but Pollock said she doesn't think any of his policies will be rolled back. She's never heard of a state withdrawing from the federal resettlement program only to rejoin it later.

Brownback's successor, Jeff Colyer — a former International Medical Corps surgeon who's twice been to Syrian refugee camps in Jordan — has been mum on the issue of refugees since assuming the office in January and did not respond to GSR's requests for comment.

Colyer hopes to be elected to his first full term as governor in November, but he first has to get past Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach in the GOP primary August 7.

Unlike Colyer, Kobach — the early frontrunner in the gubernatorial race — has been open about his refugee policy. Featured on his campaign website is a column he penned for the conservative website Breitbart News in June 2017 about the need for a temporary ban on all refugees coming to the United States.

"The refugee program must be halted temporarily so that 'extreme vetting' protocols can be put in place," Kobach wrote. "In a different day and age, such severe screening might not be necessary. But that is not the time we live in. America is under attack, and the refugee program has become a convenient tool for terrorists."

As part of Trump's immigration policy transition team, Kobach apparently floated a plan to ban Syrian refugees from entering the United States. He had previously made a national name for himself by co-writing an Arizona law that made it a crime to be in the state without documentation.

Whoever wins in November, resettlement workers in Kansas agree there's not much that person could do, officially, to make the state more unwelcome to refugees. But the next governor has the potential to further fan the flames of xenophobia that Brownback lit. And that — as Harold Schlechtweg, advocacy coordinator for the International Rescue Committee in Wichita — told GSR, would be "terrible."

Fangman is not convinced politicians in either Washington or Topeka will do the right thing and undo what's been set in place. But she hopes regular Kansans will step up, as some she knows already have, and open their hearts to the refugees who will become their neighbors.

"There was a time 40, 50 years ago that the United States was about what we could do for others. That's not the image that's being projected today," she said. "Refugees leave their country only because it's not safe and they fear death. Their courage is something I admire tremendously and is an inspiration to me."

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]

Next in this series: Waves of Central Americans travel thousands of miles to escape violence and poverty only to be sent back to the conditions they fled.