Humaira Asghar poses with children at Dar-ul-Sukun, Karachi, Pakistan, on April 16, 2024. Asghar, whose decomposed body was found July 8, visited the center six times between 2017 and 2024. (Courtesy of Dar-ul-Sukun)

Amid intense media coverage and speculation, a small group of Catholic nuns in Pakistan are defending the dignity of Humaira Asghar, a young actress and model found dead in her Karachi apartment July 8.

The Franciscan Missionaries of Christ the King who run Dar-ul-Sukun, a home for children and adults with disabilities in Karachi, have publicly remembered the 32-year-old not for the controversy that surrounded her death, but for the quiet compassion she once shared with the most vulnerable.

"She often used to visit Dar-ul-Sukun — almost every year," Sr. Catherine Wilson, head of the facility, said in a video tribute to Asghar. "She treated the children with much love, used to play with them, mingle with them, and spread her fragrance among them."

The sisters' defense of Asghar is an extension of their lifelong mission to uphold the dignity of the marginalized — in this case, an independent woman who became an easy target for moral judgment and public criticism.

The actress' death has consumed Pakistani media since the recent discovery of her body, which was found in an advanced state of decomposition. Forensic evidence suggests she may have died in October, nearly nine months before her body was found, according to media accounts.

Although various social media accounts have criticized and judged Ashgar, the sisters who knew her chose the message of mercy.

On July 12, Wilson appeared in a Facebook video, sitting with a child on her lap, speaking in Urdu about Asghar's visits to Dar-ul-Sukun, where she had offered her time and presence to children with disabilities, hugging them and handing over gifts.

"She was a living proof of her affection," Wilson said. "She even gifted a Quran to one of our teachers. It was a good thing. After her sudden departure from this world, we pray that God may bring many more Humairas among us."

The video, captioned "Dar ul Sukun remembers her with love and respect," had received more than 104,000 views as of July 25.

Other Franciscan Missionaries of Christ the King have condemned the way some people have used photos of Asghar's body in public and online. Sr. Fazilat Inayat, general secretary of the Dar-ul-Sukun Welfare Society, was particularly disturbed by how some people circulated photos of Asghar's remains.

"It raises many questions about how we view the dignity of the person — even in death," Inayat said.

She continued, "We didn't know about her personal life — only as a celebrity caring for the children at our center — but the circumstances resulted in people judging her harshly. Nobody can live alone. We do not support rebellious attitudes, complete freedom or cutting off from the family, but are saddened that nobody noticed her absence for so many months. We miss her frequent visits."

In Muslim-majority Pakistan, women who live alone often face suspicion and moral judgment, as society continues to view female independence as a threat to traditional norms. Landlords are hesitant to rent to single women, workplaces question their character, and neighbors may shun or gossip about them.

Xari Jalil, a Muslim journalist based in Lahore, praised the sisters' message.

Jalil volunteered at Dar-ul-Sukun as a student in the 1990s, clocking more than 200 hours as part of her O-level service requirement (a community service component often mandated by Pakistani private schools).

Jalil said the nuns, especially the late Sr. Gertrude Lemmens — the Dutch founder of Dar-ul-Sukun — created a home without judgment or imposition.

"It was a message based solely on humanity," Jalil said of the nuns' tribute.

"The stigma the struggling actress faced — even after death — is shameful," she said

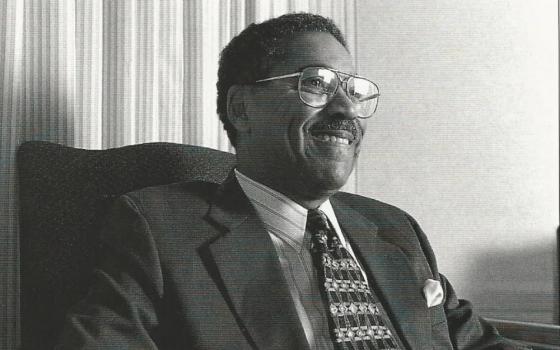

Humaira Asghar interacts with children at Dar-ul-Sukun, Karachi, Pakistan, on April 3, 2023. Asghar's remains were found July 8. (Courtesy of Dar-ul-Sukun)

Jalil contrasted the religious congregation's compassion with the discomfort many feel about people who are vulnerable or in need.

"The nuns treated us without imposing their religious beliefs," Jalil said. "I was very impressed and touched by how [the] Christian community selflessly devoted themselves to the cause."

"But some people couldn't stand the smell of urine from the beds of children who couldn't control it; they couldn't stand being hugged by kids who drooled on their clothes," she said. "But Humaira came anyway. She gave what she could. Even if it was just a drop — it mattered."

"For that alone," Jalil added, "Humaira deserves respect."

Advertisement