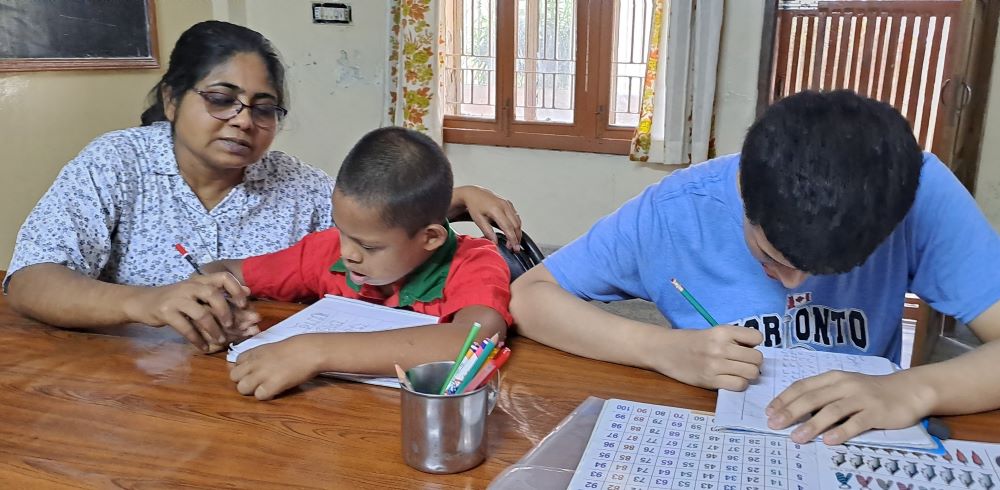

Marist Missionary Sr. Suporna Rozario teaches two children with disabilities at a center in Bangladesh. Rozario administers two centers in Dhaka, which serve 51 people (mostly children) with disabilities. (Courtesy of Suporna Rozario)

The Missionary Sisters of the Society of Mary, commonly known as the Marist Missionary Sisters, have been serving in Bangladesh since 1972. They came from the United States at the invitation of Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity, responding to the urgent need for rehabilitation in a country devastated by war. Bangladesh had just gained independence from West Pakistan on Dec. 16, 1971, and the wounds of conflict were still fresh. While Mother Teresa focused on immediate humanitarian relief, the Marist Missionary Sisters began a quiet but enduring mission of healing and empowerment.

Their early work centered on supporting women, including survivors of acid attacks, and gradually expanded as they witnessed the widespread neglect of children with disabilities. Recognizing this need, the sisters began working with Caritas Bangladesh to build the foundation for what is now a nationwide network, establishing two centers in Dhaka that currently serve 51 people (mostly children) with disabilities.

Sr. Suporna Rozario, delegate superior for the Marist Missionary Sisters in Bangladesh, directs both centers and told Global Sisters Report that they offer a vital lifeline — providing care, education, life skills and behavioral support to children while allowing parents to work with peace of mind.

Rozario recently spoke with GSR about her work and challenges.

GSR: Why did your congregation establish two centers for children with disabilities?

Rozario: When our sisters came in 1972, they saw many people with disabilities who were completely neglected. We first opened a health center in Tuital, Dhaka, where we treated patients and supported persons with disabilities. Later, we opened two centers — one in Tejkunipara, Tejgaon, and another at the Oblate Fathers' school in Naynagar, Gulshan.

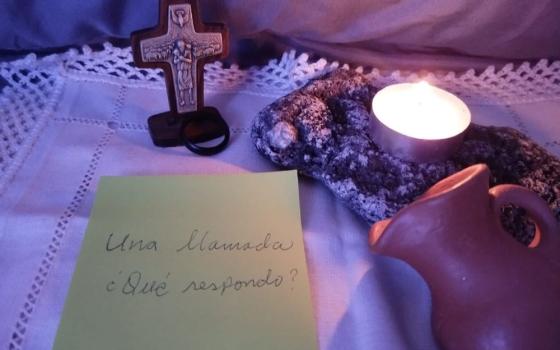

Sr. Suporna Rozario administers two centers in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which serve 51 people, mostly children, with disabilities. (Courtesy of Suporna Rozario)

Our goal was simple: to provide care and support for children with disabilities and their families. People encouraged us to open these centers because families had nowhere to turn. We wanted to create a safe space where children could learn, grow and feel valued.

What services do these centers provide?

We serve children with Down syndrome, autism, cerebral palsy and other physical or intellectual disabilities. Our priority is helping them develop basic life skills, including eating, washing hands and using the toilet, so they can be more independent. The youngest children we care for are 4. However, we also have people as old as 51.

Families trust us because their children are safe here. Many parents leave their children with us while they work or manage household chores. For example, two autistic siblings from a Muslim family attend our center; their mother struggles to care for them alone, but here they learn and interact with others.

Our centers operate from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. For those who cannot come daily, we visit homes to provide therapy and counseling. Parents face enormous stress, so we listen, encourage and guide them.

Many families are poor, especially those from slums near Naynagar. We often provide medicines, walkers, wheelchairs and special shoes when needed.

What changes do you see in children after receiving services?

When children first come, they often cannot eat or wash by themselves. After spending time with us, parents tell us their children can now manage these tasks. Some learn to write or recite poems. Not all will succeed academically, so we focus on practical skills.

I recall a boy whose mother tied him up while she worked. After joining us, his behavior improved. He stopped throwing things out the window and learned to take care of himself. His mother, who is a nurse, was deeply grateful.

Teachers work with children at one of the centers for children with disabilities in Tejkunipara, Dhaka, run by the Marist Missionary Sisters. (Courtesy of Suporna Rozario)

Aisha, 4, was born with a disability affecting her lower body. When she joined the Naynagar center in early 2023, she couldn't sit or stand. After months of therapy, she can now sit, stand, and walk short distances with special shoes and a walker. Bright and eager to learn, Aisha hopes to attend school next year.

We also teach handicrafts and manual work. One young man learned skills here, now works with us and is married.

What challenges do you face running these centers?

Safety is a concern. Once, a child ran away from our Tejkunipara center toward a busy road. Thankfully, we found him before harm occurred.

Sometimes, staff lose patience, and parents react. One mother wanted her son admitted to a regular school quickly, though he was severely disabled. When we explained, she withdrew him.

Financial constraints are constant. Most families cannot afford the monthly fee of 400 taka (about $3.25). We never refuse service to anyone, and we do not receive any government funding.

What hardships do families face?

Many fathers abandon their wives and children because of disability. Seven mothers at our centers have been left alone without support. Mothers often say they pray their children die before them because no one else will care for them. Their resilience humbles me.

Advertisement

What policies should the government adopt?

Government support is minimal. Public buses reserve seats for persons with disabilities, but healthy passengers occupy them. Monthly disability allowances are only 900 taka (about $7.30), and not everyone receives them.

Private centers are too expensive for poor families. The government should open affordable disability centers and increase allowances. Officials must also cooperate more, as securing allowances is difficult.

What else would you like to say?

The families of children with disabilities often ask for residential facilities, especially single mothers who need to work. We dream of providing this, but financial limitations prevent it. Still, our work remains a lifeline for families who struggle daily for dignity and inclusion.