An image from "The Meaning of Mandela" space in "Mandela: The Official Exhibition," a global touring exhibit about Nelson Mandela that is currently showing at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan (Courtesy of The Henry Ford/©Jim Marks)

During this November, I feel the events in our world mimic the growing darkness as winter creeps into North America. The escalating violence in Gaza seems unstoppable; the invasion of Ukraine by Russia continues in its second year; the ongoing ridicule and threats by Donald Trump continue unabated against those in the judicial system who are trying to adjudicate his multiple lawsuits.

These are the times when I wish I was more like my mammalian relatives who go into hibernation for a few months and just let life go on. I wonder, what can I do? Where can I find hope? What is there to be thankful for?

Then three recent experiences shifted how I was feeling about the world and offered me a new perspective, a different way of "seeing" our reality, just in time for the Thanksgiving season.

The first was an excellent exhibit about Nelson Mandela that I saw in Detroit. It chronicles Mandela's life, beginning when he was born into royalty within the Thembu Kingdom in the Transkei Territory; his years as an activist against apartheid; his time in prison having been arrested as a threat to the white South African government; his election as the first Black president of South Africa; and his years in retirement.

Walking through the exhibit, I felt great recognition. I had worked on sanctions against South Africa when I was in Washington, D.C. I had friends who were exiled from South Africa because of their opposition to the apartheid policies and there were sisters from my congregation who served in South Africa.

Advertisement

I also had traveled there in the 1980s and saw the effects of apartheid within the townships where the Black South Africans lived. The policies enacted by the government against Blacks — taking of their land; exploiting their labor; providing inadequate education, health care, housing and other services; preventing them from voting; and treating them as inferior and less than human — were also painfully familiar in terms of the U.S. experience of slavery.

It was when I allowed Mandela's experience in prison to sink into me that began to shift what I saw. Here was an educated man who worked tirelessly against the apartheid government. He was considered a traitor and sentenced to Robben Island, a notorious prison, for 18 years.

Here, he lived in a damp concrete cell with a straw mat. He spent his days breaking rocks into gravel being forbidden to wear sunglasses in the glaring sun, which took a toll on his eyesight.

When released from prison, he was committed to reconciliation and was willing to lead the country if elected. He was a controversial figure throughout his life. He was denounced by the right as a communist terrorist and by the left as a sellout, too eager to negotiate and reconcile with apartheid's supporters.

Nevertheless, he continued to be true to who he was as a human being. He had hope, even though he didn't know the outcome of his work, his vision of which is yet to be fulfilled in South Africa.

An image from the "Healing a Nation" space in "Mandela: The Official Exhibition," a global touring exhibit about Nelson Mandela that is currently showing at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan (Courtesy of The Henry Ford/©Jim Marks)

In the midst of the suffering and the injustice, he lived out of love and compassion. It was as if he was operating out of a different way of "seeing" reality, a different structure of consciousness that offered possibility, offered an authentic way of being human.

The second experience was my visit to Ground Zero and its museum in New York. It is sacred ground as you walk by all the names listed around the two memorial areas. I was quite aware that sacred ground exists wherever persons are annihilated by anger, terror and revenge in such numbers, but few countries have the wherewithal to honor each by name. However, what shifted my perspective was a short video describing the Boatlift.

As the Twin Towers collapsed, an enormous cloud of smoke and debris erupted and covered that part of Manhattan extending toward the water's edge. People were running for their lives and many headed to the water. There was no way out of Manhattan by land. A call went out from the Coast Guard to anyone that had a boat nearby to come to the harbor area.

The men who were interviewed spoke about how they didn't know what they were going to encounter. They just knew they had to do it. Tugboats, tour boats and private boats began to appear at the water's edge. The pilots of those boats were hard-working folks who even in the face of not knowing the extreme risk they would be assuming, knew they had to respond to the call.

Patrol Boat Hocking heads toward Lower Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001, to provide assistance following the attacks on the World Trade Center. The boat was one of many vessels that helped to ferry evacuees from Lower Manhattan and bring in emergency responders on return trips. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Army Corps of Engineers file photo)

That day, 500,000 people were transported to safety in approximately nine hours by these hundreds of vessels and their pilots who answered that call. It was the largest boatlift ever.

As I watched the video, I felt the actions of those who responded came from the best of who we are as human beings. They did not know the outcome for themselves or for those for whom they were coming, but their love for their neighbor trumped any fear or concern they had about themselves.

Watching "Boatlift" lifted my spirits and I felt gratitude for those nameless pilots who saved so many people that day.

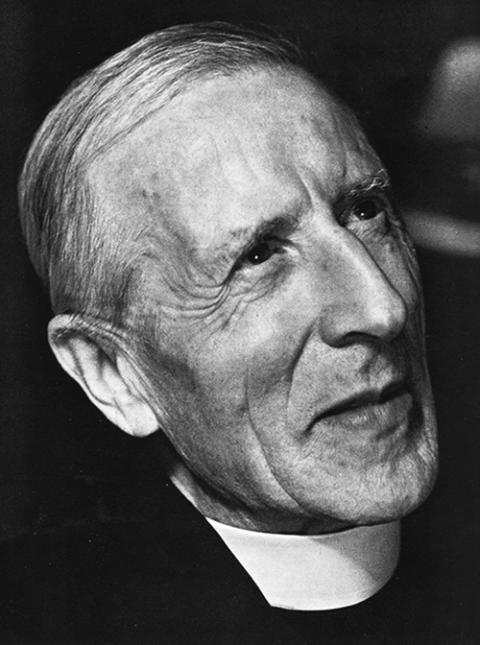

Finally, it is the inspiration of Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin that shifts my perspective. I've read his works, but recently I have been praying Teilhard De Chardin: A Book of Hours, edited by Srs. Catherine Deignan and Libby Osgood of the Congregation of Notre Dame.

Teilhard (1881-1955) was an evolutionary thinker, a paleontologist, a mystic, priest and theologian. He lived through the two world wars. He was a stretcher bearer in WWI and saw the horrors of the war.

His work was controversial within the church. Rome forbade him to write or teach on philosophical and theological subjects and he was forbidden to publish his written works. He could not attend international conferences on paleontology and his works were not to be in libraries, sold in Catholic bookstores or published in other languages.

Eventually, his works were published posthumously by a friend to whom he had given his texts.

Teilhard writes of hope and the power and possibility of love within the human person and within humanity. Today, he is a major thinker, mystic and shaper of an evolving consciousness that invites us to live out of love, compassion, faith and hope.

However, he died not knowing what would happen. The outcome did not drive his hope. His hope was rooted in love. He believed in the goodness of humanity and our evolutionary possibility.

As I reflected on these experiences, I realized that I don't want to hibernate. I need to live into the events in the world and in my life with an open heart. I need to witness to the possibility of love, compassion, faith and hope throughout our universe.

As I thought about these experiences, a favorite chant came to me. "Everything before us brought us to this moment, standing on the threshold of a brand new day." Everything and everyone who has lived the fullness of love, witnessed to a hope not rooted in outcome, lived with an open heart offering compassion to the world permeates the now. They have affected who we are and the possibility of who we can be even in the midst of great suffering.

We are not alone and we are invited to continue placing these loving energies into our lives, expanding ever outward.

Contemplative practice helps us to let go, stop clinging to outcomes, to reactions that might make one feel better but only chip away at love and hope. This Thanksgiving season, I give thanks to all those who have engaged the time they lived with courage, love, compassion, faith and hope, thereby expanding humanity's consciousness just a bit more and inviting me to do the same.