Gregoria Caceres prays next to a picture of Pope Francis placed outside the Virgin of Caacupé chapel in Buenos Aires, Argentina, April 21, 2025, after the death of Pope Francis was announced by the Vatican. Pope Francis, formerly Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, died April 21 at age 88. (OSV News/Matias Baglietto, Reuters)

Much has been written in recent days about Pope Francis — and rightly so. He has been our Pope for the past 12 years, and his pontificate will not be easily forgotten. From that March 13, 2013, when he surprised the world by forgoing many of the traditional papal vestments and stepping out onto the balcony to ask the people for their blessing at the start of his ministry, a very different kind of papacy began. So different, in fact, that even today it brings joy to many, including non-believers. It also brings discomfort to others — including believers, as well as members of the clergy and consecrated life.

Why do we say it was a "very different" papacy? There are many reasons, but let us name a few of the most important. It was a papacy that ceased to focus on ecclesial "preservation," in the sense of clinging to the past and repeating what had always been done a certain way, and instead chose to engage with the present and look toward the future. Pope Francis was not afraid to speak about real life, with all its complexities, acknowledging that the church does not have all the answers but humbly wishes to contribute to the shared search for solutions to the urgent challenges of our time.

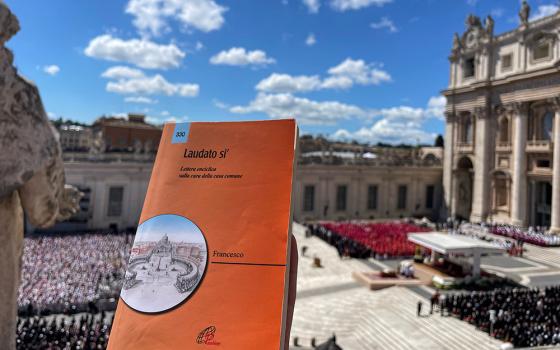

His social magisterium has made a mark not only within the church but also in the wider world, especially among world leaders. His 2015 encyclical “Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home” has been studied, reflected upon, cited and welcomed by international organizations concerned about the environmental crisis we are creating — whose most visible expression is climate change. While the encyclical does not offer solutions capable of ending a problem of this magnitude, it does constitute a prophetic call to action, urging care for our common home through an "integral ecology."

"[Francis] denounced the abuse of power often exercised against women religious, starting with the near-total lack of fair compensation for their work and extending to many other forms of mistreatment simply because they are women."

Equally significant is his 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti, in which, through the lens of the parable of the good samaritan, he addressed fraternity and social friendship as indispensable for building a just and peaceful society. He also spoke of human dignity, starting with the most vulnerable; of private property, which must never take precedence over the common good; of politics at the service of the people as the best form of governance; of the need for democracy and for economic systems that do not harm the poor; of the total rejection of the death penalty; and of the urgent need for dialogue — particularly ecumenical and interreligious dialogue.

In addition to being a pontificate attuned to the global conversation, Francis' leadership "gave back" to us the Second Vatican Council — a council that had been somewhat stalled, leading to what some called an "ecclesial regression" noticeable in previous pontificates. That is why it was easy to refer to Francis as the pope of the "ecclesial springtime." With him came fresh air into the church when he spoke of the joy of evangelizing (Evangelii Gaudium, 2013); a renewed focus on humanity and mercy, especially for the poor and the victims; increased transparency, particularly in efforts to reform Vatican finances; and the commitment to building a missionary synodal church, where laity, consecrated persons, and clergy alike recognize in baptism their fundamental equality as members of the church, and where differences in ministry exist only for the sake of service — not for prestige, power or clericalism.

Advertisement

Francis was a shepherd who "smelled of the sheep" — a call he made to ordained ministers and lived out himself. He was a pontiff who acknowledged that he was in no position to judge people based on their sexual orientation and advocated for their unconditional welcome. He also recognized that the Church could no longer sustain the systematic exclusion of women from decision-making roles and positions of authority. Concerning consecrated life — especially that of women — he denounced the abuse of power often exercised against women religious, starting with the near-total lack of fair compensation for their work and extending to many other forms of mistreatment simply because they are women.

There are many other aspects we could highlight, and we will continue to do so in the days to come, because his legacy must not be forgotten. Every path Pope Francis has opened requires continuity, commitment and strength so that nothing is lost, regardless of who the next pope may be. This is not to say that there were no unresolved issues we would have liked him to address. But this is where his journey has brought us, and what we received merits a sincere, heartfelt, and profound thank you.

Let us conclude by saying that Pope Francis gave us a Petrine ministry "with the flavor of the Gospel" — an expression he used in Fratelli Tutti (no. 1), referring to Saint Francis of Assisi. May we never forget the witness he gave us. And may each of our lives bear that same "flavor of the Gospel." Only then will we have a church that speaks to our present, a laity living out its Christian vocation, a clergy known for its service, and a consecrated life rekindled with the enthusiasm and fidelity required by the radical commitment of the vows made at profession demand.