Sr. Clarita Dolencio, 91, cares for guests in a shelter she fondly calls "the train" — a place within her convent in Quezon City, Philippines, that accommodates patients and their companions from distant provinces. (Oliver Samson)

On most mornings, 8-year-old Charls Clyde Amiscal puts on his school shoes, straightens his uniform, and steps out of the modest shelter inside the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary convent along Banawe Street. Before heading to his third grade class at a nearby public school, he waves to the nuns who have watched him grow since he arrived as a sickly 1-year-old in urgent need of care his family could not afford.

Born with an imperforate anus and one functioning kidney, Amiscal has spent his entire childhood in this shelter. What began in the 1980s as a temporary refuge for provincial patients has become one of Metro Manila's most steadfast lifelines for the country's sick poor.

Sr. Clarita Dolencio, 91, manages the shelter and vividly remembers its beginnings.

"In the 1980s, many patients from the provinces needed treatment in Manila but had no relatives here," she said.

One of the rooms in their convent was cleared and turned into a shelter. As more families came, the sisters — mostly Belgian missionary nurses — brought patients from remote towns to the capital, often after long jeepney and bus rides.

"It was born out of necessity," Sister Clarita said. "People needed a place. So we opened the door."

Sr. Clarita Dolencio (in white) sits with the occupants of the shelter she and the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary administer in their convent in Quezon City. (Oliver Samson)

The shelter originally offered free stays. Later, the sisters asked for a donation of 50 pesos per person ($.84 at the current exchange rate). When Sister Clarita took over in 2015, it was raised to 100 pesos ($1.68) — still the same today. It covers lodging and three meals a day.

"We cannot survive on 100 pesos," she said. "But that is all many can give."

The sisters stretch every peso. They cook using firewood gathered around the compound and save gas for emergencies. The half wall that protects the front of the shelter was donated by St. Theresa's College of Quezon City's high school class of 1974.

"People have helped us so much," Sister Clarita said. "We are very grateful."

The shelter runs on a network of generosity. The Tzu Chi Foundation covers the board and lodging of patients they refer. Teresian alumni send rice, cash and supplies. Others donate canned goods, soap or cleaning materials.

Members of the media, particularly from GMA Network, have also referred patients to the shelter, Sr. Marcy Badian explained.

She added that the shelter is in dire need of more food and that it is challenging to "figure out where and whom to refer patients," especially those with complex health situations.

A large part of the shelter's strength is drawn from the people it accommodates.

Advertisement

"We have no staff," Sister Clarita said. "The bantays [companions of patients] help us clean, cook and maintain the place. They treat it like home."

"People don't know of many shelters like this," Sister Marcy said. "Few places welcome patients from the provinces who have nowhere to stay while undergoing treatment in Metro Manila."

Under Sister Clarita's guidance as a social worker, the shelter also offers social, spiritual and livelihood support.

Patients and their companions make doormats from old clothes and pillows stuffed with cleaned plastic wrappers — an activity that provides income, a form of emotional therapy, and helps unclog drainage systems by keeping plastic waste out of waterways.

Sister Marcy said that half of their sales go to the patients. "The rest helps keep the house running."

Spiritually, the place is transformative for many.

"One person told me, 'It is only here that I learned how to pray,' " Sister Clarita said.

Residents join nightly prayers and participate in Sunday Mass. During Holy Week, they reenact the Last Supper with patients volunteering as apostles.

"It has become a community of faith," Sister Clarita said. "They help each other be strong."

"People don't realize the risks of welcoming strangers into our compound," Sister Marcy added. "But we trust in God's protection. That is why we continue this mission."

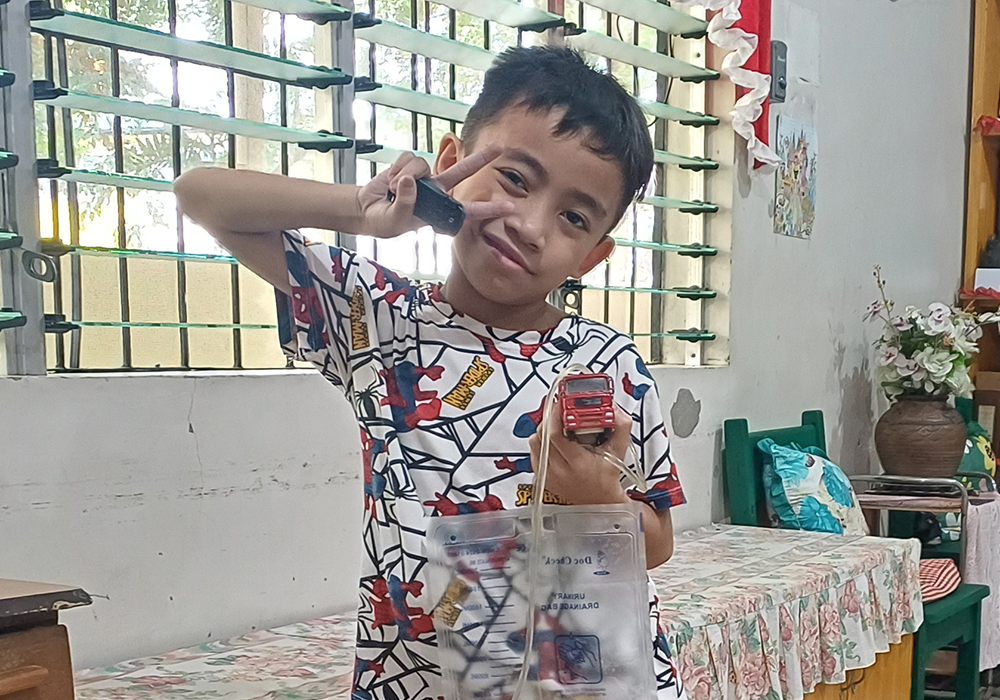

Charls Clyde Amiscal, an 8-year-old who has been living in the sisters' shelter in Quezon City since he was 1, holds his toy jeepney and urine bag. (Oliver Samson)

The shelter is filled with stories of hardship and resilience.

Charls Clyde and his mother, Joegicel, arrived from Bohol when he was 1. Each ultrasound revealed the gradual loss of one kidney. His remaining kidney was scheduled for surgery on Nov. 27. (He has not yet undergone the surgery.) The Tzu Chi Foundation supports their stay, and Joegicel now assists the sisters in the shelter.

"She is amazing and knows the ins and outs of the lodging house," Sister Clarita said.

Charls Clyde, who once feared sleeping alone, now has friends at school and dreams of becoming a doctor "so he can treat sick people." He also keeps a box of toys he has collected from visitors who pass through the convent and the shelter — small gifts that have brightened his long stay.

Another patient is a young woman with two holes in her heart and pulmonary hypertension. She and her mother, Christine, traveled from Leyte for treatment at the Philippine Heart Center. Her operation is tentatively scheduled for January, also with the Tzu Chi Foundation's help. They will remain in the shelter until then.

The sisters who run the shelter are mostly elderly.

"Since we are old, people now come to us," Sister Clarita said with a smile. "But the mission continues."

Finances remain their biggest challenge. Last year, Teresian alumni donated 86,000 pesos (about $1,455), which funded meals and repairs. Upcoming needs include gutter work and kitchen improvements.

Still, the sisters remain hopeful.

"It is a very good, necessary mission," Sister Clarita said firmly. "If people can share clothes, goods or support, it is a big help."

After four decades, the shelter remains a quiet sanctuary — humble, steady and sustaining lives one day at a time. Here, compassion is lived out daily in its simplest form.

"We give them more than a place to sleep," Sister Clarita said. "We give them hope. And I pray that this mission continues long after we are gone."