Members of the Loreto Sisters photographed at Loreto Abbey in Rathfarnham, Dublin, by Mother Michael Corcoran (Courtesy of IBVM archives/UCD Digital Library)

University College Dublin's Digital Library has launched a unique collection of more than 500 images taken between 1902 and 1908 by Mother Michael Corcoran (1846-1927) of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The superior general of the Irish branch of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Loreto Sisters) was a self-taught photographer who used her camera to capture religious sisters, ministries, pupils, employees and friends of Loreto communities in Ireland and across the world. The digitized images draw from Corcoran's extant photographic albums and a few surviving glass lantern slides.

The newly digitized images are part of the work of a research center at the university, Convent Collections. Established in 2015 by Deirdre Raftery, a professor of the history of education, the research team of postdoctoral and doctoral scholars draws on the archives of women religious in Ireland to carry out research on areas such as vocation, missionary activity, global influence, education and health care. The expertise of archivists and technologists is drawn together on digitization projects and projects involving recorded oral histories.

The Mother Michael Corcoran digital collection is Raftery's most recent digital project, conducted together with UCD Digital Library and funded by an award from UCD Research.

An elected fellow of the Royal Historical Society, Raftery received the Distinguished Historian Award from the Conference on the History of Women Religious in 2019. Her most recent book, Teresa Ball and Loreto Education: Convents and the Colonial World, 1794-1875, was published in March 2022 and is already into its second print run.

Deirdre Raftery, a professor of the history of education at University College Dublin (Courtesy of Deirdre Raftery)

In the book, Raftery explores how Mother Teresa Ball became a pioneer of girls' education in Ireland and beyond when she returned from the Bar Convent in York, England, in 1821 and opened Loreto Abbey in Rathfarnham, Dublin, in 1822. Some photographs that Corcoran took at the end of the 19th century are included in the book.

In 1902, Corcoran became the first superior general of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary to undertake an international visitation of Loreto communities, traveling to India, Spain and Australia. She also spent time in Rome. Her photographic collection includes images captured while she traveled. There are also images from 1905 of the motherhouse at Loreto Abbey in Rathfarnham, where St. Teresa of Kolkata would stay as part of her novitiate in 1928, and images of Loreto Convent in Balbriggan and the surrounding countryside taken between 1906 and 1907.

GSR: Born in 1846, she was the youngest ever appointed to the office of mother general at the age of 42. (Nobody as young has been appointed since.) What was Mother Michael Corcoran's significance?

Raftery: She is probably the most important Catholic woman educator of her time in Ireland. She was very active in promoting academic education for girls and supported the opening up of university education to Irish women. She believed in providing girls with an education equivalent to that of boys.

She also wanted to ensure that sisters who were teachers would be properly trained, and she traveled to Cambridge to see how teacher education was carried out in England.

What was she trying to do in relation to third-level women's education?

Loreto pupils had been very successful in the intermediate examinations, a second-level school examination system that was established in 1878. Loreto schoolgirls proved themselves to be as academic as boys, and Corcoran believed that they should have the opportunity to continue on to university.

At that time, Irishwomen couldn't attend university classes, but they could be prepared for the university exams of the Royal University of Ireland. Corcoran set up a women's college, Loreto College, St. Stephen's Green, Dublin, where young women could be prepared for the RUI degree examinations and for diplomas from prestigious music colleges in London. She hoped that Loreto College would be given university status.

As it happened, Archbishop William Walsh threw his support behind the Dominicans, allowing them to found the first — and only — Catholic women's university in Ireland. They opened St. Mary's University College in 1893, which had a very short life because of the opening up of mixed-sex university education in Ireland.

Mother Michael Corcoran of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary with her camera in Australia in 1903 (Courtesy of IBVM archives/UCD Digital Library)

Corcoran's work for higher education is not captured in her photographic collection, but what is captured is her interesting ideas about pedagogy.

She had a wide vision of what education is. It wasn't just about books. She had a curiosity about life. She used her large collection of lantern slides for pedagogic purposes so that students could see the wider world: what India was like or what a lengthy ship journey was like.

She also brought Ireland to the outside world. She famously sent Irish harps to Loreto schools in Australia so that the girls would learn Irish music.

What kind of woman was Mother Michael Corcoran?

She was a very bright woman and a strong leader. Her tenure as superior general of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary was unusually long: She served five terms of office, which meant that she had very significant influence on girls' education both at Loreto's Irish schools and also internationally.

She wasn't reelected by her peers so many times for no reason. I think her leadership was appreciated.

A measure of her strength was the fact that she went out on visitation and made her way to Spain, India and Australia. She was away for a long time: She went in October 1902, and she completed her first visitation in 1903 in Rome but didn't get back to Ireland until January 1904.

Why are her photographs significant?

We see the world through the eyes of a 19th-century nun. Photography as a female pastime had become popular in the period in which she was taking photographs. So she doesn't stand out in that respect, and we can't make claims for her as an exceptional female photographer, but what is exceptional is the fact that she was a nun — essentially living apart from the world — who was a photographer. I'm not aware yet of any other 19th-century nun who created such a large photographic collection.

She's not a perfect photographer by any means, but she is a very good amateur photographer.

These images widen our vision of what convent life was like and what religious sisters were like. Prior to this collection, it was very hard to see what ordinary life inside an enclosure might have been like. Not all of the photographs are taken inside the convent; some are outdoors, showing nuns enjoying leisure time.

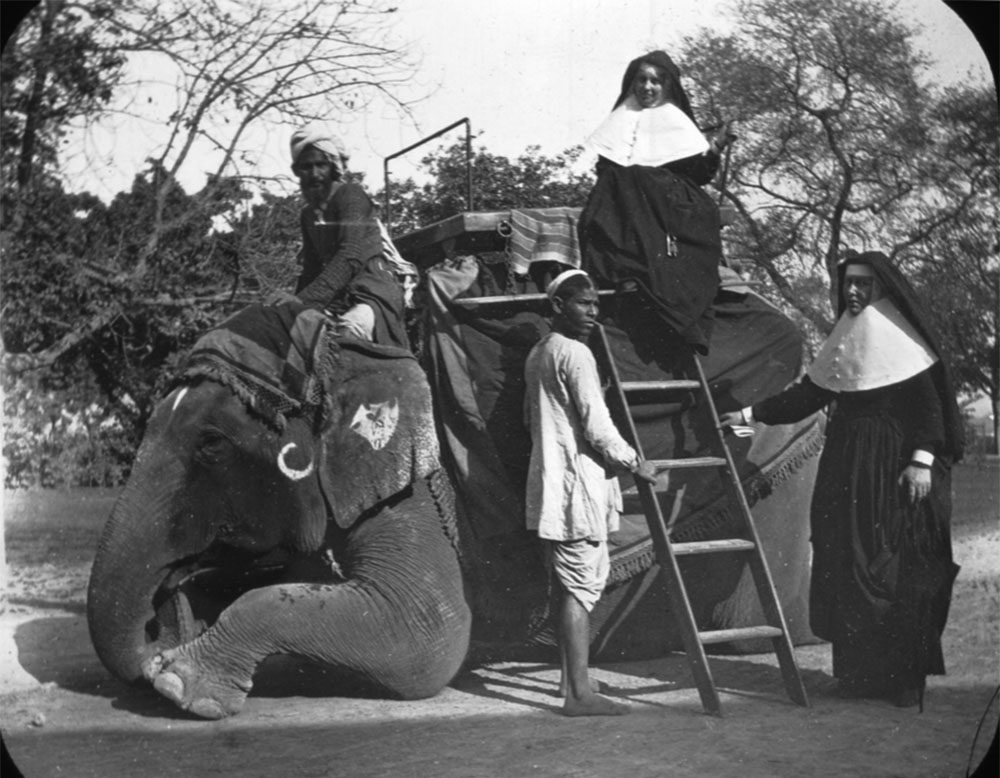

Some of the images are quite whimsical. They show she had a sense of humor. There are photos of sisters riding upon an elephant in India and sitting on top of a haycart in Ireland. Other images show nuns on board a ship.

One of Mother Michael Corcoran's constructed images, taken in India during her visitation from 1902 to 1903 (Courtesy of IBVM archives/UCD Digital Library)

There is also a good collection of pictures of Irish life, such as the photographs taken of farm workers at Loreto Abbey Rathfarnham and some taken in Balbriggan, in the countryside. They show families at work and children at play.

Some of the pictures of childhood at the turn of the century are really delightful and very nicely constructed. They will be of particular interest to people interested in childhood studies.

The publication of these images as a digital collection is the fruit of a collaboration between University College Dublin and Loreto/IBVM Ireland. How did that come about?

I set up UCD Convent Collections about eight years ago. It is an academic research group that harnesses the expertise of UCD Digital Library for certain projects. The Mother Michael Corcoran collection would be a case in point.

We have also made successful competitive bids for grants. For example, I won a grant from the Royal Irish Academy for a new project using the archives of the Sisters of Mercy; that is ongoing at the moment.

I have also won awards from the Irish Research Council for projects using convent archives that were part of the output during our national Decade of Centenaries. [Ireland's Decade of Centenaries remembers the events that took place from 1912 to 1922, including the War of Independence and the Civil War. At the end of these turbulent and transformative events, the island of Ireland was partitioned into two states, one of which was independent.]

One project that was a big success was "Loreto the Green, and 1916," a unique digital collection drawing on the IBVM archives, which was launched as part of the Decade of Centenaries. It also features as a digital exhibition at Google Arts & Culture.

My project digitizing the surviving letters of Presentation foundress Nano Nagle has also attracted hundreds of online viewers.

Advertisement

For my research for the new Teresa Ball biography, I was consulting the IBVM/Loreto archives and came across the photograph albums of Mother Corcoran. I felt they really needed to be out in the world, as they would be of interest to far more people than just those researching women religious.

What is the main reason for digitizing these images?

It is about preservation and good practice. With an album of photographs, if somebody wants to use it, they have to handle it. There is always a danger that the photographs could be compromised by sunlight or by overhandling. The spines of the albums could break over time.

Digitization removes the need for people to handle the albums. There is no need henceforth for the albums to ever be photographed or copied again.

Researchers using the digital versions can zoom in very close on each photograph or lantern slide. They can see every detail. Some would argue that they can actually see them better by looking at the digitized images on a computer or tablet device.

The project also democratizes sources by putting them into a digital library under a Creative Commons license — they are open to everybody. We have five or six different projects with UCD Digital Library that are all from congregational collections, and it opens them up to a much wider research audience.

These digital projects have also increased the awareness of congregational archives in Ireland, which is a great outcome.

Your book, Teresa Ball and Loreto Education, has just been released. It provides important insights into the nun who brought the charism of Venerable Mary Ward to Ireland, from where it spread around the world. What is Teresa Ball's significance?

Teresa Ball is one of a small handful of really important early 19th-century foundresses that drove the growth of Catholic education in Ireland. She had been sent to the Bar Convent in York to be educated. She later returned there to enter the Institute [of the Blessed Virgin Mary], and she loved the Bar Convent.

However, Daniel Murray, archbishop of Dublin, asked her to come home to make a foundation in Ireland. It was a big sacrifice, but she did it. Teresa Ball established Loreto Abbey in Rathfarnham, which became the motherhouse for all IBVM houses founded from Ireland.

From there, she made many foundations around Ireland, and she also sent her Irish nuns out to make foundations in India, Gibraltar, Spain, Mauritius, England and Canada. She was considering the possibility of an Australian foundation before her death. It later came to fruition.

Ball sent many women religious out into the world. She gave them a chance to exercise their own leadership. A large collection of her letters has survived, and one of the things I try to do in the book is use her own words to show how she developed leadership in other people. She had a very clear sense, from the way she was formed in York, of what leadership should be like and how to form other leaders.

She carefully picked the women she sent out to lead new foundations. She told them that if they had been chosen for leadership, it was because they were able for leadership and they were ready for leadership.

One of her great gifts was that she was able to develop leadership in other people. It is what people nowadays call mentoring for leadership. She was doing it in the 1830s.